Dr Christopher Bell’s Views on Zemey Rinpoche’s Yellow Book

H.E. Kyabje Zemey Rinpoche

Recently, the Tibetan Journal of Literature featured a compelling article by Dr. Christopher Bell, an Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Stetson University, shedding light on a pivotal work in the Dorje Shugden saga.

Dated July 26, 2023, Bell’s commentary delves into the intricacies of a 1973 publication by H.E. Kyabje Zemey Rinpoche titled Swelling Roar of Amassed Clouds of Nectar and Black Clouds Flickering with Nooses of Fearsome Lightning: The Teachings of the Capable Father Lama Conveying the Origins of the Great Protector of the Teachings, Mighty Dorjé Shukden, who is Great with Power and Strength.

The book was commonly known as the ‘Yellow Book” after the colour of its cover. It soon became notorious for its misunderstood and controversial content – a set of accounts of the wrathful means that Dorje Shugden divined in the past to be necessary to keep the teachings of Lama Tsongkhapa’s lineage from being corrupted. This corruption is possible when practitioners mix traditional Gelug practices with elements from other schools, such as the Nyingma lineage, which hold differences in doctrinal perspectives from the Gelug.

Kyabje Zemey Rinpoche never intended for his book to be published. It initially began as a compilation of personal notes from teachings he received from H.H. Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche. In 1973, it was published without his permission. As a result, it added complexity to the Dorje Shugden narrative.

Some quarters interpreted the book’s publication as evidence of a hostile attempt by the Gelug school to assert its pre-eminence over the other schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The book is often cited to corroborate the alleged evil nature of Dorje Shugden, and the malicious agendas of those who engage in the protector’s liturgies and rituals.

Those who oppose Dorje Shugden’s practice also say that the book’s content validates H.H. the 14th Dalai Lama’s efforts to forcefully ban the deity’s practice in the past. It is only in recent years that the situation has eased, lightening the challenges faced by Dorje Shugden practitioners.

In his article “The Yellow Book of Dzemé Rinpoché by Dzemé Losang Palden”, Dr. Bell notes that the modern foundational view of Dorje Shugden was cast by the writings of Georges Dreyfus, “The Shuk-den Affair: History and Nature of a Quarrel.” Whether intended or not, it was this writing that gave Dorje Shugden its 20th-century representation as “a strict sectarian divinity that enforces Geluk purity and hegemony, which is at odds with the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s ecumenical endeavours.”

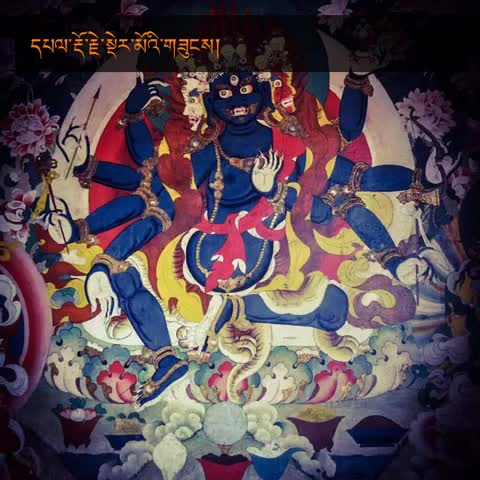

A thangka of the wisdom protector Dorje Shugden which belongs to His Holiness Trijang Rinpoche

This depiction of Dorje Shugden shows that two distinct objectives are being conflated: the Gelug school’s desire to preserve their teachings from contamination, and the misunderstood aspiration to dominate other sects.

While the Gelug spiritual pillars of the time — luminaries such as H.H. Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche, H.H. Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche, H.E. Kyabje Zemey Rinpoche and others — undoubtedly defended their lineage as being matchless, this does not make them extremists and fanatical crusaders of their beliefs. Instead, it is a puritanical stance that almost all other Tibetan Buddhist schools share.

This is a point that Georges Dreyfus acknowledges and writes,

“The sectarian elements of the Yellow Book were not unusual and do not justify or explain the Dalai Lama’s strong reaction.”

It is important to avoid assuming that Gelug lamas who have this zeal automatically harbour secret political and hegemonic ambitions aimed at dominating and imposing their beliefs on other schools. There are historical records that speak of the Gelug’s forced conversion of the Kagyu and rival sects such as the Jonang school, during the reign of the 5th Dalai Lama. It is inappropriate to attribute such aggression to the religious beliefs of the Gelug. Instead, these actions were the political decisions made by officers in the 5th Dalai Lama’s government (who also happened to be Gelug) as they sought to eliminate perceived challenges both external (e.g. the Kagyu) and internal (e.g. the popularity of Tulku Drakpa Gyaltsen).

Against the common misunderstanding that the 14th Dalai Lama’s ban on Dorje Shugden was in reaction to Gelug agitations towards the other schools, as Zemey Rinpoche’s book is said to be witnessing, Dr. Bell emphasises that this is not so. He notes that the book’s content is merely notes taken to supplement a single verse in Trijang Rinpoche’s seminal writing on Dorje Shugden, Music Delighting the Ocean of Protectors, published six years before the Yellow Book.

The stanza in question extols Dorje Shugden as the warrior deity of the Yellow Hat teachings, portraying him as unsparing to eliminate even the most formidable and influential individuals who allow the mixing and corruption of the pure Gelug teachings.

This strong sentiment originated from Pabongka Rinpoche’s work 40 years earlier. Pabongka Rinpoche has since been depicted as a politically motivated and highly sectarian spiritual leader who aggressively targeted the Nyingma sect and aimed to eradicate it.

His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama

To the contrary, Pabongka Rinpoche was renowned for advising his disciples against the pitfall of forsaking the Dharma by denigrating one lineage while extolling another. He lacked any political aspirations. After the parinirvana of H.H. the 13th Dalai Lama, Pabongka Rinpoche was asked to take on the role of Regent of Tibet, which would have given him the opportunity to pursue any sectarian and hegemonic ambitions he may have had. However, he declined the position, opting instead to stay in his modest hermitage with minimal possessions.

Dr. Bell lists some stories from the book that portray Dorje Shugden as ferocious, intemperate, and violent. To ordinary people, violence in the conventional sense is antithetical to the Buddhist path which emphasises compassion, non-harming, and the cultivation of wisdom. From that framing, it is easy to surmise that Dorje Shugden is a demonic mischief, a malicious deity that has to be dealt with.

However, the “violence” in the Yellow Book must be taken in the context of Tibetan Buddhism. Violence and ritual killing (whether literal or allegorical) are very much a feature of the Vajrayana path. At the core of Tibetan Buddhism is the liberation of sentient beings from suffering, paving the way for all beings to achieve the enlightened state. At times, this liberation takes the form of an untimely death or killing.

The reason for these portrayals is based on the concept that enlightened beings, driven by deep compassion and omniscience, may perform activities that seem detrimental to ordinary beings in order to remove obstacles, eradicate negative energies, and ultimately free human beings from suffering. The focus lies on the underlying purpose of the deed, which is perceived as driven by empathy and a profound comprehension of the essence of existence.

One apt example of this compassionate destruction can be seen in the biography of the translator Ra Lotsawa Dorje Drak who brought and popularised the Yamantaka practice in Tibet. Today, the Yamantaka ritual is favoured by high practitioners of the Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya and Gelug lineages. All speak of Yamantaka’s supreme power to overcome obstacles, counter illness, heal, and prolong life. They say Yamantaka is emptiness personified.

And yet, Ra Lotsawa’s journey to bring this tantra to the people to be preserved for posterity is marked by sinister episodes of the translator “liberating” 13 lives. These were similarly powerful lamas and adepts who manifested opposition to Yamantaka, claiming that it was a demonic ritual that would lead adherents to the hell states. That set the stage for Ra Lotsawa to engage in psychic duels with them, killing 13 in the process. These were highly attained beings and important people, much like those who supposedly fell victim to Dorje Shugden’s compassionate wrath in the Yellow Book.

Jacob Dalton’s work, Taming of Demons, is another example. It explores the myth of Rudra, the powerful embodiment of all things evil who sought to destroy the Dharma and plunge the cosmos into a suffering-filled pit. Rudra was finally stopped when a group of enlightened beings confronted the demon, subsequently killing him with ritual murder, a gruesome process that is described in detail in some interpretations. Rudra was then resurrected as a divine being who swore an oath to protect the Buddhadharma. He has since been known as the great Mahakala.

In his article, Dr. Bell also writes about one of the earliest and strongest critics of Dorje Shugden and the Yellow Book, a great Sakya Lama, Dhontog Rinpoche. Dhontog Rinpoche claimed that Rahula, one of the three main Nyingma Dharma Protectors, was responsible for the death of Zemey Rinpoche and Pabongka Rinpoche. The irony is unmistakable.

According to Mahayana Buddhist theory, the violent activities of the Protector may be considered justified. In that context, it was a sacred conflict fought to prevent the contamination of a revered lineage, namely the dissemination of Lama Tsongkhapa’s authentic teachings to future generations.

Dr. Bell’s emphasis on certain points of the book raises an intriguing question: why did the additional notes made by Zemey Rinpoche on one verse of a prayer by Trijang Rinpoche receive strong criticism, while previous writings on similar topics did not? What had changed in the Tibetan political landscape that rendered his notes so inflammatory during that period?

Dr. Bell stopped short of postulating. Perhaps the answer lies in an article that my friend and colleague Seow Choong Liang sent to me recently. It was written by Frederic Richard and was appropriately titled Pabongka, Shugden, and the Rimé Movement.

It is insightful writing that presents a crucial perspective of the Dorje Shugden conflict — the tug-of-war between the Gelug school’s objective to preserve the teachings of Lama Tsongkhapa and the Dalai Lama’s role in uniting the diverse religious traditions through the concept of Rimé, a cross-purpose between the Gelug establishment and the Tibetan government’s aspirations.

Richard writes that when the Manchu Qing monarchy disintegrated in 1912, the 13th Dalai Lama declared the end of the ‘Priest-Patron’ relationship between Tibet and Manchu China. His Holiness aimed to establish a government, supported by a formidable military force by enlisting the assistance of the young aristocracy, with the objective of safeguarding Tibetan independence. According to Melvyn Goldstein (Goldstein, Melvyn C. 1991. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press) there were three distinct groups in Lhasa at that time, each advocating for their own interests and opposing the others:

- the military commanders, who were greatly influenced by secular ideologies;

- the Gelug priesthood, who prioritised their tradition over the politics of the government;

- and the government officials, who were dedicated to enhancing the authority of the government they relied upon.

Dorje Shugden became the embodiment of the second, the prioritising of the purity of Lama Tsongkhapa’s lineage, while the Rimé movement became the symbol of the enhancement of the authority of the Tibetan government, embodied in the institution of the Dalai Lama.

And when seen from that lens, it becomes logical why the Dorje Shugden issue only became ablaze each time the Tibetan government sought to consolidate its power:

- first when the 5th Dalai Lama ascended to power;

- next when the 13th Dalai Lama declared independence from its traditional patron in Manchu China;

- and finally in the 1970s when the 14th Dalai Lama sought to unite the Tibetan diaspora after a decade in exile with no signs in sight of regaining Tibet.

In each of these cases, the call was for the Gelug predominance to be diminished. And each time, the resulting resistance by the Gelug luminaries was not directed at the Dalai Lama’s attempt to unify Tibet but to preserve teachings that transcend borders and labels relevant only to a temporal space.

Dr Bell did not arrive at any decisive conclusion. The intelligent and fair-minded academic in him probably would not let him sway to shifting winds. But if he did not leave us with what he thought, he did give a hint as to what he felt. He writes:

“Finally, there is the sense that whether one is the harmer, like Dorjé Shukden, or the harmed, like the heretical masters, both are empty of inherent existence, and these violent interactions are ultimately part of the divine play of enlightened beings.”

It is a sentiment that finds harmony with Trijang Rinpoche’s teachings in Music Delighting the Ocean of Protectors.

The more one delves into the conflict, the more evident it becomes that the sacredness of the enlightened Dharma Protector was never the core issue. It was never truly a theological dispute. The argument over whether Dorje Shugden is legitimate served as a stand-in for a broader political struggle between conflicting governing entities. It is a debate that in essence, has become moot by the passage of time. Both the institution of the Dalai Lama and the Gelug theocracy are no longer the authoritative forces they once were simply because Tibet is no longer the country it once was. Neither can now decide how Tibet is to be governed.

Unfortunately, the damage to the Tibetan community and to Tibetan Buddhism is significant. Perhaps the highest attrition lies in the missed opportunities for those who could have benefited from the protection and blessings of a very powerful Buddha, were it not for the pungency of this religious infighting.

Dr Bell’s writing on the Yellow Book comes at an opportune time. Active aggressions against the protector have stopped since 2020 when His Holiness the Dalai Lama ever so deftly signalled the easing of his hard stance against the practice of Dorje Shugden. There is now a chance to shift our focus away from a narrower scope of Tibetan politics into a broader examination of the state of sentient beings in the kaliyuga. Perhaps then, we may see the importance of revisiting and transcending this now redundant quarrel, for the benefit of all practitioners and the preservation of the profound teachings of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Yellow Book of Dzemé Rinpoché

Dzemé Losang Palden

Translated by Christopher Bell

Click here to download in PDF format.

Source: https://journaloftibetanliterature.org/index.php/jtl/article/view/53/134

For more interesting information:

- Nechung – A Dissertation by Christopher Bell

- Why Accepting Dorje Shugden Is Good for Tibetan Democracy

- Why can’t the Dalai Lama ‘bind’ Dorje Shugden?

- H.E. Tsem Rinpoche’s first live streaming!

- The Dorje Shugden category on my blog

- Manjushri Nagarakshasa comes to KFR!

- They were not wrong

- Can Tibetan Lamas Make Mistakes?

- My plea to His Holiness the Dalai Lama

- My plea to His Holiness (Tibetan) | ངའི་༧གོང་ས་མཆོག་ལ་སྙན་ཞུ་ཞུ་རྒྱུར།

- The Fourteenth Dalai Lama & Dorje Shugden | ༧གོང་ས་ཆེན་པོ་སྐུ་འཕྲེང་བཅུ་བཞི་པ་མཆོག་དང་རྡོ་རྗེ་ཤུགས་ལྡན། | 十四世达赖尊者与多杰雄登

- The Fifth Dalai Lama & Dorje Shugden | ༧གོང་ས་ལྔ་པ་ཆེན་པོ་དང་རྡོ་རྗེ་ཤུགས་ལྡན། | 第五世达赖尊者与多杰雄登

- Dorje Shugden: My side of the story

- Should there be a separate autonomous Dorje Shugden state? Part 1

- Should there be a separate autonomous Dorje Shugden state? Part 2

- To Sum It Up

- The Buddhist Divide – An Unholy Campaign against Religious Freedom

- Tibetan Leadership’s New Anti-Shugden Video

- Updated: Dorje Shugden Teaching Videos

- The Dalai Lama Speaks Clearly About the Dorje Shugden Ban

- Nechung – The Retiring Devil of Tibet

Please support us so that we can continue to bring you more Dharma:

If you are in the United States, please note that your offerings and contributions are tax deductible. ~ the tsemrinpoche.com blog team

Dorjé Shukden is a controversial Tibetan Buddhist protector deity, believed by some to be a wrathful spirit and by others to be an enlightened Buddha. The controversy that arose from this divided understanding over the last fifty years has impacted the Tibetan Buddhist community globally and continues to be relevant to observers and practitioners of Buddhism the world over. The Yellow Book, based on its cover. It was composed by Kyabje Zemey Rinpoche in 1970, but it was not published until 1973. Kyabje Zemey Rinpoche never intended for his book to be published but somehow it was published without his permission. According to the introduction, Kyabje Zemey Rinpoche authored this book in 1970 based on teachings given by Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche, the junior tutor to the 14th Dalai Lama.The original intention of this book was to be complementary material to Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche’s book, Music Delighting An Ocean of Protectors, which was published six years before the Yellow Book. The Yellow Book did not circulate widely until several years later. It is a collection of cautionary tales and teachings but sadly some influential powerful officials and people who had corrupted the Gelug lineage . Interesting read.

I am looking forward to finish reading this book.

Thank you Rinpoche and Martin for this interesting sharing.

❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹 As Buddhists let’s take better care of fellow colleagues and create a better world for future generations of sangha (a valuable and adorned jewel) ❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹❤️🩹 May everyone aspire to be this adornment among human beings which is an astonishing sight to behold. There should definitely be nil quarrels and conflicts and disturbing disputes in the Buddhist community because of how incredible and amazing Buddhas (gurus) are. Live and let live. 🙏