Machik Labdron

b.1055 – d.1149

Tradition: Zhije and Chod ཞི་བྱེད་དང་གཅོད།

Geography: Tibetan Autonomous Region

Historical Period: 10th Century ༡༠ དུས་རབས། / 11th Century ༡༡ དུས་རབས།

Institution: Dingri Langkhor དིང་རི་གླང་འཁོར།; Zangri Kangmar ཟངས་རི་ཁང་དམར།

Name Variants: Machik Labkyi Dronma མ་ཅིག་ལབ་ཀྱི་སྒྲོན་མ།

The life story of Machik Labdron (ma gcig labs sgron) has been recounted in several different Tibetan hagiographies (rnam thar), with considerable differences among them. According to these sources, Machik was born in 1055 in a village called Tsomer (mtsho mer), situated in lower Tamsho (tam shod) in E Ganwa (e’i gang ba) of the Labchi (labs phyi) region, or, alternatively, in Gyelab (gye’i labs) in Keugang (khe’u gang), in the eastern part of the Yarlung (yar klungs) valley. Her father, Chokyi Dawa (chos kyi zla ba), was the chief of Tsomer village; her mother, Lungmo Bumcam (klungs mo ‘bum lcam), gave birth to two other children: a son, Lotsawa Keugang Korlodrak (lo tswA ba khe’u gang ‘khor lo grags) and a daughter, remembered simply as Bume (bu med).

19th Century painting of Machig Labdron as a wisdom dakini. Image credit: himalayanart.org. Click on image to enlarge.

Machik took an early interest in Buddhist teachings and became a student of Drapa Ngonshe (grwa pa mngon shes, 1012-1090); she would prove an able reader of the Prajnaparamitasutra texts and would provide this service to lay persons on behalf of her teacher. Drapa Ngonshe eventually advised her to study with Kyoton Sonam Lama (skyo ston bsod nams bla ma, d.u.), from whom she received an initiation for the teaching named the “Outer Cycle of Maya” (phyir ‘khor ba’i lam du sgyu ‘phrul).

Following an encounter with a peripatetic Indian yogi known alternately as Topa Bare (thod pa ‘ba’ re, d.u.) or Topa Bhadra (thod pa bhadra), she became his consort and bore three sons: Nyingpo Drubpa (snying po grub pa), Drubchung (grub chung), and Yangdrub (yang grub), and two daughters called Kongcham (kong lcam) and Lacham (la lcam). Some sources have it that she had only two sons, named Drubpa and Kongpokyab (kong po khyab), and one daughter, Drubchungma (grub chung ma). Later in her adult life, Machik returned to dressing as a renunciate with a shaved head and travelling to receive teachings. She eventually settled in a cave at Zangri Kangmar (zangs ri khang dmar), where a community formed around her.

Machik’s principal male disciples included her heart son Gyelwa Dondrub, also known as Gyelwa Drubche (rgyal ba grub che), who became a lineage holder of her teachings. Some have, most likely in error, listed Gyelwa Dondrub as her biological son, although this appears unlikely. Her grandson was Tonyon Samdrub (thod smyon bsam grub, d.u.), known as the “Snowman of Shampogang” (sham po gangs pa’i gangs pa). The tradition of black-hat-wearing Chod practitioners known as “Gangpa” (gangs pa) originated with him. A second student, Kugom Chokyi Sengge (khu sgom chos kyi seng ge, d.u.), also became renowned for his transmission of Chod (gcod), a practice grounded in the Prajnaparamitasutra directed toward cutting through ego-clinging and erroneous patterns of thinking.

This nineteenth century painting depicts Machik Labdron with tantric deities and mahasiddhas. Image credit: himalayanart.org. Click on image to enlarge.

According to several traditional sources, at some point fairly early in her career Machik met and received teachings from the Indian yogi Padampa Sanggye (pha dam pa sangs rgyas, d.u.) the well-known teacher of Zhije (zhi byed) teachings which are focused on the pacification of suffering. It has become standard to attribute the transmission of the Chod lineage from Padampa to Machik, although there is little material evidence that such a transmission took place. Indeed, some accounts of the transmission rest solely on Machik seeing Padampa from afar. Frequently invoked in support of this argument is a prose work by Aryadeva the Brahmin, Padampa Sanggye’s maternal uncle, considered to be a root text (gzung rtsa) for several of the Chod lineages that would develop later. (The text is titled either Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa tshigs su bcad pa chen mo or Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa mang ngag.)

Alternate versions of the Chod transmission history suggest that the teachings were passed from Padampa to Machik’s teacher, Sonam Lama, and then to her. However, such claims are at odds with another traditional claim, namely that Machik’s system of Chod was the only Buddhist teaching transmitted from Tibet to India, rather than from India to Tibet.

Karma Kagyu Field of Accumulation painting with the Fifteenth Karmapa, Kakyab Dorje, as the last lineage holder at the time of the compositions creation. Image credit: himalayanart.org. Click on image to enlarge.

Extant texts that are traditionally directly associated with Machik include the Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa zab mo gcod kyi man ngag gi gzhung bka’ tshoms chen mo, the Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa’i man ngag yang tshoms zhus lan ma, the Nying tshoms chos kyi rtsa ba, the Thun mong gi le lag brgyad pa, the Thun mong ma yin pa’i le’u lag brgyad pa and the Khyad par gyi le lag brgyad pa. Of these, the Bka’ tshoms chen mo is the only one that can presently be historically situated through the existence of an annotated outline and a commentary ascribed to the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje (kar+ma pa rang ‘byung rdo rje, 1284-1339). In the Third Karmapa’s Bka’ tshoms chen mo tikka, he mentions texts by Machik which may no longer be extant, including the Gnad thems, Khong rgol, Gsang ba’i brda’ chos, as well as an Nang ngo sprod. Dzarong Lama Tendzin Norbu (rdza rong bla ma bstan ‘dzin nor bu, 1867-1940) also mentions the Gnad thems, Gsang ba’i brda’ chos and Nang ngo sprod, adding the Gzhi lam slong in his study entitled Gcod yul nyon mongs zhi byed kyi bka’ gter bla ma brgyud pa’i ram thar byin rlabs gter mtsho.

Mid-20th century painting of Machik Labdron and the Chod refuge field displaying teachers and deities. Image credit: himalayanart.org. Click on image to enlarge.

མ་ཅིག་ལབ་སྒྲོན།

མ་ཅིག་ལབ་ཀྱི་སྒྲོན་མ་ནི། དབུ་མའི་དགོངས་པ་ཇི་སྙེད་ཅིག་གཏན་ལ་ཕབ་ཅིང་ མཚན་ཉིད་རིག་པ་སྨྲ་བའི་བོད་ཀྱི་བུད་མེད་ཞིག་ཡིན་ཏེ། ཁོང་གིས་གཅོད་ཀྱི་ལྟ་བའི་སྐོར་ལ་གསལ་སྟོན་དང་ཕྱོགས་སྡོམ་མཛད་ཅིང་ལག་ལེན་དངོས་ཀྱིས་ཉམས་སུ་བླངས་པ་ལས་མཚན་ཡོངས་སུ་གྲགས་པར་གྱུར། གཅོད་ཅེས་པ་ནི་ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པའི་གདམས་ངག་ལ་གཞི་བཅོལ་བའི་ཉོན་མོངས་ཞི་བར་བྱེད་ཅིང་བདག་འཛིན་དྲུང་ནས་གཅོད་པར་བྱེད་པའི་ཉམས་ལེན་ཐུན་མོང་མ་ཡིན་པ་ཞིག་ཡིན། འདི་ནི་དུས་ཕྱིས་སུ་སྐྱ་སེར་ཉམས་ལེན་པ་མང་པོས་ཉམས་བཞེས་མཛད་དེ་བོད་བརྒྱུད་ནང་བསྟན་ཙམ་མ་ཟད། བོན་ལུགས་སུའང་འདི་དང་ཆ་འདྲ་བ་ཞིག་དར་ཡོད་དོ།།

Teachers

- bsod nams bla ma བསོད་ནམས་བླ་མ།

- a ston ཨ་སྟོན།

- Drapa Ngonshe གྲྭ་པ་མངོན་ཤེས། b.1012 – d.1090

- Padampa Sanggye ཕ་དམ་པ་སངས་རྒྱས། b.11th cent. – d.1117

Students

- rgyal ba don grub རྒྱལ་བ་དོན་གྲུབ།

- chos kyi seng+ge ཆོས་ཀྱི་སེངྒེ།

Bibliography

- Chos kyi seng ge. 1974. Zhi byed dang gcod yul gyi chos ‘byung rin po che’i phreng ba thar pa’i rgyan. In Gcod kyi chos skor, pp. 411-597. New Delhi: Tibet House.

- Dpa’ bo gtsug lag phreng ba. 2003. Chos ‘byung mkhas pa’i dga’ ston. Sarnath, India: Vajra Vidya Library, 1369-1371.

- Edou, Jérôme. 1996. Machik Labdron and the Foundations of Chöd. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications.

- ‘Gos lo tswa ba gzhon nu dpal. 2003 (1478). Deb ther sngon po. Sarnath, Varanasi: Vajra Vidya Institute.

- Gyatso, Janet. 1985. “The development of the gcod tradition.” In Soundings in Tibetan Civilization. B.N. Aziz and M. Kapstein, eds, pp. 320-341. New Delhi: Manohar

- Kollmar-Paulenz, Karénina. 1993. ‘Der Schmuck der Befreiung’: Die Geschichte der Zhi byed-und gCod-Schule des tibetischen Buddhismus. Wiesbaden: Harrowitz Verlag.

- Kollmar-Paulenz, Karénina. 1998. “Ma gcig lab sgron ma – The Life of a Tibetan Woman Mystic Between Adaption and Rebellion.” Tibet Journal 23 (2), 11-32.

- Lo Bue, Erberto. 1994. “A Case of Mistaken Identity: Ma-gcig Labs-sgron and Ma-gcig Zha ma.” In Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of International Association of Tibetan Studies, pp. 481-490. Per Kvaerne, ed. Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture.

- Ma gcig lab sgron. 1974. Phung po gzan skyur gyi rnam bshad gcod kyi don gsal byed. In Gcod kyi chos skor. Byams pa bsod nams, ed., pp. 10-410. New Delhi: Tibet House.

- Machik Labdron. 2003. Machik’s Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chöd: A Complete Explanation of Casting Out the Body as Food (Phung po gzan skyur gyi rnam bshad gcod kyi don gsal byed). Sarah Harding, trans. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion.

- Orofino, Giacomella. 1987. Contributo allo studio dell’ insegnamento di Ma gcig Lab sgron. Supplemento n. 53 agli Annali, vol. 47, Napoli: Istituto Universitario Orientale.

- Orofino, Giacomella. 2000. The great wisdom mother and the gcod tradition. In Tantra in Practice. David Gordon White, ed., 320-341. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rdza sprul ngag dbang bstan ‘dzin nor bu. 1972. Gcod yul nyon mongs zhi byed kyi bka’ gter bla ma brgyud pa’i rnam thar byin rlabs gter mtsho. Gangtok: Sonam T. Kazi.

- Roerich, George, trans. 1996. The Blue Annals. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

Source: Michelle Sorensen, “Machik Labdron,” Treasury of Lives, accessed July 22, 2018, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Machik-Labdron/5644.

Michelle Sorensen is Assistant Professor in the Philosophy and Religion Department at Western Carolina University. She completed her PhD in Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University in 2013.

Published April 2010

Disclaimer: All rights are reserved by the author. The article is reproduced here for educational purposes only.

About Treasury of Lives

The Treasury of Lives is a biographical encyclopedia of Tibet, Inner Asia, and the Himalaya. It provides an accessible and well-researched biography of a wide range of figures, from Buddhist masters to artists and political officials, many of which are peer reviewed.

The Treasury of Lives is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. All donations are tax deductible to the fullest extent of the law. Your support makes their important work possible. For information on how you can support them, click here.

Source: https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Machik-Labdron/P3312. Click on image to enlarge.

For more interesting information:

- The Dorje Shugden category on my blog

- The Tsongkhapa category on my blog

- The Great Lamas and Masters category on my blog

- Three True Stories you must read!

- 84 Mahasiddhas

- Inspiring Nuns and female practitioners

- Achi Chokyi Drolma – Chief Protectress of the Drikung Kagyu

- The Great Female Master- Jetsun Lochen Rinpoche

- The Samding Dorje Phagmo – The Courageous Female Incarnation Line

- Gemu Goddess of Mosuo

Please support us so that we can continue to bring you more Dharma:

If you are in the United States, please note that your offerings and contributions are tax deductible. ~ the tsemrinpoche.com blog team

CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers verlenen professionele verhuizingen in Amsterdam.

CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers bieden vakkundige verhuisdiensten aan particuliere klanten. De Verhuizers bij CTN

Verhuizers assisteren klanten bij een soepele verhuizing.

CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers faciliteren het inpakken van verhuisdozen voor een zorgeloze verhuizing.

CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers verschaffen verhuiswagens die veilig en betrouwbaar zijn. De Verhuizers van CTN Verhuizers

organiseren spoedtarieven voor dringende verhuizingen. CTN Verhuizers

Verhuizers verschaffen deskundige hulp bij seniorenverhuizingen. CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers assisteren bedrijfsverhuizingen met ervaring

en kwaliteit. De Verhuizers bij CTN Verhuizers verschaffen verhuisliften voor zware meubels.

CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers regelen de verhuizing van appartementen in Amsterdam.

CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers verlenen een gratis online offerte voor verhuisdiensten. CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers

verschaffen een persoonlijke aanpak voor elke verhuizing.

De Verhuizers bij CTN Verhuizers verschaffen erkende verhuisdiensten met vergunningen. CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers helpen klanten met verhuischecklists

voor een gestructureerde verhuizing. CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers verlenen opslagmogelijkheden voor

tijdelijke inboedels. CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers verlenen verhuiswagens die flexibel inzetbaar zijn. De Verhuizers van CTN

Verhuizers coördineren de verhuizing van internationale klanten. CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers verlenen verhuisdiensten die verzekerd en veilig

zijn. CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers verschaffen professionele

verhuisdiensten met een uitstekende beoordeling. CTN Verhuizers Verhuizers helpen klanten met verhuisadvies en verhuisgebeurtenissen in Amsterdam.

Machig Labdron, Tibetan tantric Buddhist master and yogini regarded as an emanation of Prajnaparamita the Great Mother of all the Buddhas, Aryatara, and Kharchen Yeshe Tsogyal, Machig . Historical texts portray her as the originator of the Chod lineage which she developed in Tibet.

Machig’s conception and birth were accompanied by numerous auspicious dreams and signs. Amazing most significant was the appearance of the syllable AH on the baby’s forehead. As a child she already developed her spiritual gifts where by the age of eight she could recite the whole text sutra. She soon known for her depth of Buddhist scholarly knowledge and extensive recitation skills . Interesting read .

Thank you Rinpoche for this sharing of a brief niography of Machig Labdron.

Machik was born in 1055 in a village called Tsomer, situated in lower Tamsho in E Ganwa of the Labchi region. Machik took an early interest in Buddhist teachings and became a student of Drapa Ngonshe. Machik met and received teachings from the Indian yogi Padampa Sanggye the well-known teacher of Zhije teachings which are focused on the pacification of suffering. Thank you Rinpoche and blog team for this short history of Machik Labdron ??

Interesting short life story of Machik Labdron , fortunate to come across this article. I did google more of her to understand better. Machik Labdron was a renowned 11th-century Tibetan tantric Buddhist practitioner. It seem that she is considered to be both a dakini and a deity an emanation of Prajnaparamita . Historically, she was an outstanding teacher, and a founder of a unique transmission lineages of the Vajrayana practice of Chöd In one of a rare paintings in nineteenth century did depicts Machik Labdron with tantric deities and mahasiddhas…….very beautiful painting.

Thank you Rinpoche for this sharing.

Nice short video of a new LED signage reminding us of who we can go to for blessings in case of need: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EBwrkaKUoH0

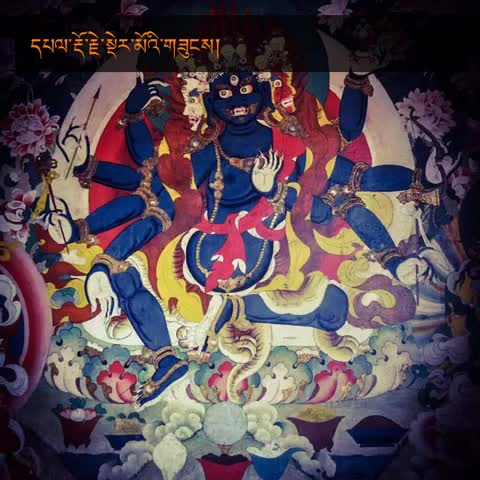

Listening to the chanting of sacred words, melodies, mantras, sutras and prayers has a very powerful healing effect on our outer and inner environments. It clears the chakras, spiritual toxins, the paths where our ‘chi’ travels within our bodies for health as well as for clearing the mind. It is soothing and relaxing but at the same time invigorates us with positive energy. The sacred sounds invite positive beings to inhabit our environment, expels negative beings and brings the sound of growth to the land, animals, water and plants. Sacred chants bless all living beings on our land as well as inanimate objects. Do download and play while in traffic to relax, when you are about to sleep, during meditation, during stress or just anytime. Great to play for animals and children. Share with friends the blessing of a full Dorje Shugden puja performed at Kechara Forest Retreat by our puja department for the benefit of others. Tsem Rinpoche

Listen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZbzgskLKxT8&t=5821s