Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen

b.1235 – d.1280

Tradition: Sakya ས་སྐྱ།

Geography: Mongolia

Historical Period: 13th Century ༡༣ དུས་རབས།།

Institution: Sakya ས་སྐྱ།; Lang Na གླང་སྣ།; Jyegu Dondrub Ling སྐྱེ་དགུ་དོན་གྲུབ་གླིང།; Sakya Monastery ས་སྐྱ་དགོན་པ།

Offices Held: Seventh Sakya Tridzin of Sakya Monastery

Name Variants: Chogyel Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen ཆོས་རྒྱལ་འཕགས་པ་བློ་གྲོས་རྒྱལ་མཚན།; Drogon Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen འགྲོ་མགོན་འཕགས་པ་བློ་གྲོས་རྒྱལ་མཚན།; Lodro Gyeltsen བློ་གྲོས་རྒྱལ་མཚན།; Pakpa Lukye འཕགས་པ་ལུག་སྐྱེས།

Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen (‘phags pa blo gros rgyal mtshan) was born in 1235 in Ngari (mnga’ ris) into the illustrious Khon (‘khon) family that had recently established themselves at Sakya in Tsang. His father was Sonam Gyeltsen (bsod nams rgyal mtshan, 1184-1239), the younger brother of the great scholar Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyeltsen (sa skya pan di ta kun dga’ rgyal mtshan, 1182-1251), who is commonly referred to as Sapan. His mother was Kunga Kyi (Kun dga’ kyid).

In 1244 Pakpa and his younger brother Chana Dorje (phyag na rdo rje, 1239-1267) traveled to the Mongol court of Godan Khan, the son of the Mongol leader Ododei, with their uncle Sakya Pandita. As Goden was in Yunnan at the time, they did not meet until 1247. Tibetan historians have it that Sapan went to Mongolia to serve as religious preceptor, but it is more likely that he was summoned to serve as proxy for a Tibetan acceptance of Mongolian rule. Some scholars have speculated that Pakpa and his brother, the heirs to the Khon family, accompanied their uncle as hostages. However, it is more likely that they went along simply as disciples and attendants to their teacher and uncle.

Another old thangka of Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen. Image credit: himalayanart.org. Click on image to enlarge.

Like his uncle Pakpa was fully ordained, having received his vows from Sapan the year they left for Mongolia. He was given his initial instruction in the Vinaya from Sherab Sengge (she rab seng gye).

Pakpa remained in Mongolia after the death of his uncle in 1251. Godan’s influence was on the wane, having lost succession first to his brother Guyug and again in 1251 to his cousin Mongke. In 1253 Mongke’s brother, Khubilai invited Pakpa to his newly built city of Kaiping (latter known as Shangdu), presumably in part because he believed the Tibetan Buddhist lama could help justify the Mongol’s rule of China. In fact the invitation had been for Sapan, but Pakpa went in his place. In 1254, on his way to meet the Khan, Pakpa went on a teaching tour in Kham where he visited various monasteries, converting several, including Dzongsar (dzong gsar) and Jyegu Dondrub Ling (skye dgu don grub gling) from Bon to the Sakya tradition.

Once Pakpa was settled at Khubilai’s court, he gained a significant degree of influence and authority. Beginning in 1258 Pakpa performed Buddhist initiations and empowerments for the Khan and, in that same year, participated in a debate with leading Daoists. According to Tibetan historians Khubilai judged him to be the winner, a victory that moved the Khan to burn Daoist texts and force prominent Daoists to convert to Buddhism.

Despite this incident, Khubilai was, like his predecessors, an ecumenical ruler who surrounded himself with religious leaders of many traditions, including other Tibetans. Pakpa, however, had a unique position in regards to both Mongols and Tibetans and was therefore particularly suited to form an alliance with Khubilai. Having been raised in Goden’s court, Pakpa was intimately familiar with Mongol values and culture. He was also well known and highly esteemed among Tibetan Buddhists, as the nephew of Sapan and a member of the powerful Khon family.

Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen (right) and his uncle Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyaltsen (left) surrounded by the lineage teachers of the Guhyasamaja Tantra; Akshobhyavajra, Manjuvajra and Avalokita. Image credit: himalayanart.org. Click on image to enlarge.

In 1259 a succession struggle in Mongolia resulted in the fragmentation of the Mongolian Empire, and Khubilai, who was then in charge of the Chinese territories, turned his focus entirely to the conquest of the Song Empire. In 1260 Khubilai appointed Pakpa national preceptor (guoshi, 國師). The young monk had spent the previous years initiating Khubilai into Hevajra and Mahakala mandalas, but again, until the appointment, Pakpa was one of several lamas courted by Khubilai. Now, however, Khubilai saw lamas who had supported his opponents as enemies. He had Karma Pakshi, the Second Karmapa (1204-1287), who had established relations with his rival for control of Mongolia, arrested and burned on a stake. (According to legend, after three days of flames had left him unharmed everyone gave up, and the lama was banished to Yunnan, to return to central Tibet a decade later much reduced in influence.)

Pakpa developed a close relationship with the Khan and a particular affinity with his wife Chabi, whose biographical accounts describe as an extremely fervent and faithful Buddhist disciple. Khubilai abolished the appanage system that Mongke had established decades earlier, and made the Sakya the (nominal) ruler of the entire country. The national preceptor was made chief of the administrative offices that were to oversee the territory, the Bureau of Tibetan and Buddhist Affairs, the Xuanzhengyuan (named after the hall in which the officials were received).

According to one Sakya history of Pakpa’s tenure in the Xuanzhengyuan, the Emperor initially intended to raise a tax on Tibetan monasteries and initiate a draft of Tibetans into corvée labor. Pakpa is said to have protested, insisting that Tibet’s resources would be overstrained by the taxes and draft and threatening to leave the court and return to Tibet. Tibet is said to have thereby been spared the burden of tax and corvée.

In 1264 Khubilai Khan sent Pakpa and his brother back to Tibet to convince Tibetans to accept Mongol rule. Pakpa brought along with him the famous Jasa Mutik (‘ja’ sa mu tig), the “Pearl Edict” which Sakya historians incorrectly claim granted Pakpa control of Tibet; in fact it only exempted Sakya from taxes and corvée, something that Khubilai was giving to other sects as well. Tibetan historians have also claimed the earlier document has as having granted Sakya lordship over the thirteen myriarchies, but since these were not established until the census of 1268, this is clearly mistaken.

The roles that Pakpa and Chana Dorje were expected to play remain unclear, and in any case their supposed authority over Tibet was consistently challenged by Drigung Monastery (‘bri gung dgon). Chana Dorje passed away in 1267, and, whatever the original plan had been, the abbot of Sakya, Shakya Zangpo (shAkya bzang po, d. 1270), who had run the monastery since Sakya Pandita left, was given the newly created office of Ponchen (dpon chen), and given civil and military authority over all of Tibet. The office of Ponchen was subordinate to the national preceptor. The refusal of Drigung to accept the arrangement forced Khubilai to send in troops to enforce Sakya control, and within a year Mongol control of Tibet was restored. Soon after, a census was conducted, a postal system was devised, taxes were imposed and a Tibetan militia was formed – all under Mongol direction. The system of governance devised for Tibet would consist of a State Preceptor (Pakpa being the official first), who was in charge of Buddhists throughout the empire as well as in Tibet (but who would live in China) and an a second Mongol-appointed official, the Ponchen, who would live in Tibet and administer the region more directly. This system was in place for the next eighty years.

Pakpa wrote about the appropriate relationship between a king and religious rulers, helping to bolster Mongol imperial authority. He also identified Khubilai Khan as Manjusri, the bodhisattva of wisdom and encouraged the identification of Khubilai as a cakravartin or Universal Emperor. Pakpa helped incorporate Buddhist rituals into the Yuan court, which competed with but did not replace traditional Chinese Confucian court rituals. It seems that Pakpa’s efforts helped Tibetans to see Khubilai Khan as a universal ruler in the Buddhist sense, and as the legitimate Emperor of China. Pakpa and Khubilai Khan also deepened their relationship through marriage alliances; Pakpa’s younger brother, nephew, and grandnephew all married Mongol princesses.

Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen (right) and his uncle Sakya Pandita, Kunga Gyaltsen Pal Zangpo (left). Image credit: himalayanart.org. Click on image to enlarge.

Pakpa’s collected works fill three volumes and he is credited with having developed the theory of Buddhist ruler-ship that delineated mutually dependant spheres of secular and religious authority. This model, which he and Khubilai were meant to embody as cooperative religious and secular rulers, was purportedly worked out with the aid of Khubilai’s wife Chabi. She settled a dispute between the two men early on in their relationship when neither was content to acknowledge the other as holding a higher position. This arrangement was ritually represented by Khubilai sitting on a lower throne when receiving teachings from Pakpa, and Pakpa sitting on a lower throne when Khubilai conducted court business.

Pakpa was able to use the power and other resources of his position to further his uncle’s scholarly and cultural projects. With the aid of the Sakya Ponchen, Pakpa had the Lhakhang Chenmo (lha khang chen mo) built at Sakya, effectively transforming the Khon family estate into what is commonly known as Sakya Monastery. Pakpa and his successors established Sakya as a center of scholarly activity. They sponsored the translation of poetry, literature, and metrics. Sapan is credited with having had established the study of the five sciences across Tibet, and Pakpa maintained the momentum through his writing and polemics. It was also largely thanks to Sakya influence that Sanskrit poetry became the basis of high literary culture during their time.

In 1270 Pakpa returned to China to receive the title of Imperial Preceptor (dishi, 帝師), a title that is generally considered, at least in part, to have been a response to his invention of the short-lived imperial script. The following year Khubilai declared the establishment of the Yuan Dynasty, with its capital at Dadu (modern Beijing). He spent the next few years in semi-retirement, returning to Sakya in 1274. There he convened a council of lamas at Chumik Ringmo (chus mig ring mo), known as the Chumik Chokor (chu mig chos ‘khor), ostensibly for religious discussions, but probably to persuade the various traditions’ leaders to accept Mongol-Sakya rule. It was a fruitless effort if that was its purpose, as Drigung continued to resist.

In 1280, the year after Khubilai conquered the remnants of the Song, Pakpa died at Sakya, allegedly poisoned by an unpopular Ponchen.

འཕགས་པ་བློ་གྲོས་རྒྱལ་མཚན།

འཕགས་པ་བློ་གྲོས་རྒྱལ་མཚན་ནི། དཔལ་ས་སྐྱ་པའི་ཤིན་རྟའི་སྲོལ་འབྱེད་ས་སྐྱ་གོང་མ་ལྔར་གྲགས་པའི་ཁོངས་ནས་ལྔ་པར་བགྲངས། ཁོང་ས་སྐྱ་པཎཌིཏ་ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་གྱི་ནུ་བོ་རྗེ་བཙུན་བསོད་ནམས་རྒྱལ་མཚན་གྱི་སྲས་སུ་སྐུ་འཁྲུངས། ཆུང་དུས་རང་གི་ཁུ་བོ་ས་པཎ་དང་ལྷན་དུ་སོག་པོ་གོ་དན་རྒྱལ་པོའི་སར་ཕེབས། སྐུ་ནར་སོན་པས་བོད་དང་སོག་པོ་ཡོན་གོང་མའི་འབྲེལ་བའི་ཐད་ཞབས་འདེགས་རྒྱ་ཆེར་བསྒྲུབས། ཡོན་ཧུ་པི་ལི་སེ་ཆེན་རྒྱལ་པོ་དང་འབྲེལ་བ་དམ་ཟབ་ཀྱིས་བོད་སོག་པོས་དབང་བསྒྱུར་བའི་དུས་སུ་ཁོང་གི་རླབས་ཆེའི་མཛད་འཕྲིན་ལས་ས་སྐྱའི་དགོན་ཆེན་དེ་ཉིད་སྲིད་དབང་གི་བསྟི་གནས་སམ་བོད་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་ས་ལྟ་བུར་འགྱུར། ཡོན་གོང་མའི་རྒྱུ་སྦྱོར་གྱི་མཐུས་ས་སྐྱ་ལྷ་ཁང་ཆེན་མོ་གསར་བཞེངས་རྒྱ་སྐྱེད་མཛད་པས་ད་ལྟ་གཞི་རྒྱ་ཆེ་བའི་ས་སྐྱ་དགོན་པ་འདི་ལྟ་བུར་གྱུར། དེ་སྔ་སོག་པོར་ཡི་གེ་མེད་པས་ཁོང་དང་ས་པཎ་རྣམ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་སོག་པོའི་སྐད་ཡིག་ཐོག་བསྒྱུར་རྒྱུའི་ཐུགས་བཞེད་ཀྱིས་ཧོར་ཡིག་གསར་གཏོད་མཛད་པར་གྲགས། ཡིག་གཟུགས་འདི་ལ་ཆེ་བསྟོད་ཀྱིས་འཕགས་པའི་ཡི་གེའང་ཟེར།

Teachers

- Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyeltsen ས་སྐྱ་པཎྜིཏ་ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན། b.1182 – d.1251

- bsod nams rgyal mtshan བསོད་ནམས་རྒྱལ་མཚན།

- byang chub rgyal mtshan བྱང་ཆུབ་རྒྱལ་མཚན།

- shrI ta tha ga ta b+ha dra ཤྲཱི་ཏ་ཐ་ག་ཏ་བྷ་དྲ།

- Chim Namkha Drak མཆིམས་ནམ་མཁའ་གྲགས་པ། b.1210 – d.1289

- shes rab rin chen ཤེས་རབ་རིན་ཆེན།

- Sanggye Yarjon སངས་རྒྱས་ཡར་བྱོན། b.1203 – d.1272

- shes rab dpal ཤེས་རབ་དཔལ།

- grags pa seng+ge གྲགས་པ་སེངྒེ།

- grags pa seng+ge གྲགས་པ་སེངྒེ།

- rdo rje ‘od zer རྡོ་རྗེ་འོད་ཟེར།

- shes rab seng+ge ཤེས་རབ་སེངྒེ།

- dbang phyug brtson ‘grus དབང་ཕྱུག་བརྩོན་འགྲུས།

- shes rab ‘od zer ཤེས་རབ་འོད་ཟེར།

- ‘bras khud pa འབྲས་ཁུད་པ།

- dkon mchog dpal དཀོན་མཆོག་དཔལ།

- Yeshe Bumpa ཡེ་ཤེས་འབུམ་པ། b.1242 – d.1328

Students

- Shongton Dorje Gyeltsen ཤོང་སྟོན་རྡོ་རྗེ་རྒྱལ་མཚན། b.early 13th cent. – d.late 13th cent.

- Lotsawa Chokden Lekpai Lodro མཆོག་ལྡན་ལེགས་པའི་བློ་གྲོས། b.early 13th cent. – d.late 13th cent.

- Zhangton Konchok Pel ཞང་སྟོན་དཀོན་མཆོག་དཔལ། b.mid 13th cent. – d.1317

- kun dga’ blo gros ཀུན་དགའ་བློ་གྲོས།

- sangs rgyas sras སངས་རྒྱས་སྲས།

- dar ma rgyal mtshan དར་མ་རྒྱལ་མཚན།/li>

- kun dga’ smon lam ཀུན་དགའ་སྨོན་ལམ།

- phyag na rdo rje ཕྱག་ན་རྡོ་རྗེ། b.1239 – d.1267

- jin kim ཇིན་ཀིམ།

- Yeshe Rinchen ཡེ་ཤེས་རིན་ཆེན། b.1248 – d.1294

- sangs rgyas dpal སངས་རྒྱས་དཔལ།

- tshul khrims rgyal mtshan ཚུལ་ཁྲིམས་རྒྱལ་མཚན།

- Rinchen Gyeltsen རིན་ཆེན་རྒྱལ་མཚན། b.1238 – d.1279

- chos sku ‘od zer ཆོས་སྐུ་འོད་ཟེར།

- Sanggye Yarjon སངས་རྒྱས་ཡར་བྱོན། b.1203 – d.1272

- Dharmapalaraksita དྷརྨ་པཱ་ལ་རཀ་ཥི་ཏ། b.1268 – d.1287

- kun dga’ grags pa ཀུན་དགའ་གྲགས་པ། b.1230 – d.1303

- sangs rgyas ‘bum སངས་རྒྱས་འབུམ།

- rgyal mtshan bzang po རྒྱལ་མཚན་བཟང་པོ།

- gzhon nu seng+ge གཞོན་ནུ་སེངྒེ།

- shes rab ‘bum ཤེས་རབ་འབུམ།

- gzhon nu ‘bum གཞོན་ནུ་འབུམ།

- kun dga’ rgyal ba ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་བ།

- mdo sde dpal མདོ་སྡེ་དཔལ།

- ‘jam dbyangs shes rab ‘od zer འཇམ་དབྱངས་ཤེས་རབ་འོད་ཟེར།

- ‘od zer ‘bum འོད་ཟེར་འབུམ།

Images

DAMARUPA. Damarupa and Avadhutipa, two Indian Siddhas. On the left is the siddha Damarupa holding upraised in his right hand a damaru drum and a skullcup in the left. On the viewer’s right is Avadhutipa holding a skullcup to the heart with the left hand and pointing downwards with the right hand. The third figure from the top in the right column is Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen. More at himalayanart.org

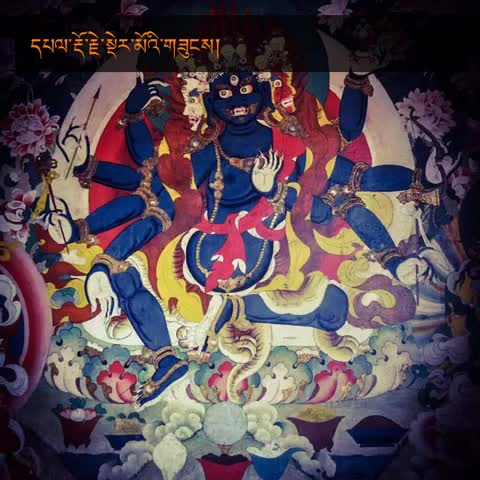

MAHAKALA – PANJARNATA. Panjarnata Mahakala is the protector of the Hevajra cycle of Tantras. The iconography and rituals are found in the 18th chapter of the Vajra Panjara (canopy, or pavilion) Tantra, an exclusive ‘explanatory tantra’ to Hevajra itself. It is dated to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century. The figure at the top right corner is Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen. More at himalayanart.org

MAHAKALA – PANJARNATA. Panjarnata Mahakala is the protector of the Hevajra cycle of Tantras. The iconography and rituals are found in the 18th chapter of the Vajra Panjara (canopy, or pavilion) Tantra, an exclusive ‘explanatory tantra’ to Hevajra itself. It is dated to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century. The figure at the top right corner is Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen. More at himalayanart.org MAHAKALA – PANJARNATA. Mahakala surrounded by the stylised flames of pristine awareness. Emanating forth from the licks of flame are messengers in the shapes of various animals, black crows, black dogs, wolves, black men and women. The figure at the top right corner is Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen. More at himalayanart.org

MAHAKALA – PANJARNATA. Mahakala surrounded by the stylised flames of pristine awareness. Emanating forth from the licks of flame are messengers in the shapes of various animals, black crows, black dogs, wolves, black men and women. The figure at the top right corner is Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen. More at himalayanart.org

Bibliography

- Blo bzang chos grags and Bsod nams rtse mo. 1988. ‘Gro mgon ‘phags pa blo gros rgyal mtshan. In Rtsom yig gser gyi sbram bu. Xining: Mtsho sngon mi rigs dpe skrun khang, p. 145.

- Bsod nams ‘od zer and Zla ba seng ge. 1976. Sa skyar ‘gro mgon chos rgyal drung du byon zhing chos kyi gtam gyis phan tshun tshim par mdzad pa’i skor. In Grub chen o rgyan pa’i rnam par thar pa byin brlabs kyi chu rgyun. Gangtok: Sherab Gyeltsen Lama, pp. 130-133.

- Chos ‘phel rgya mtsho. 2000. ‘Gro mgon chos rgyal ‘phags pa. In Gtsang dgon pa’i gdan rabs dbyangs can phang ‘gro’i gdangs snyan. Xiling: Mtsho sngon nyin re’i tshags par khang gi par khang, pp. 39-43.

- Davidson, Ronald M. 2005. Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Dungkar Lobzang Khrinley. 2002. Dunkar Tibetological Great Dictionary (Dung dkar tshig mdzod chen mo). Beijing: China Tibetology Publishing House.

- Gold, Jonathan C. 2008. The Dharma’s Gatekeepers: Sakya Paṇḍita on Buddhist Scholarship in Tibet. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Jam dbyangs blo gter dbang po, et al. Bla ma dam pa chos kyi rgyal po rin po che’i rnam par thar pa rin chen phreng ba. In Lam ‘bras slob bshad. Dehra Dun: Sakya Centre, pp. 145v-169v.

- Mi nyag mgon po. 1996-2000. ‘Phags pa blo gros rgyal mtshan gyi rnam thar mdor bsdus. In Gangs can mkhas dbang rim byon gyi rnam thar mdor bsdus. Beijing: Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig dpe skrun khang, pp. 63-70.

- Mu po. 202. ‘Gro mgon chos rgyal ‘phags pa. In Gsung ngag rin po che lam ‘bras bla ma brgyud pa’i rnam thar kun ‘dus me long. Beijing: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang, pp. 19-24.

- Nor brang o rgyan. 2006. ‘Gro mgon chos rgyal ‘phags pa. In Nor brang o rgyan gyi gsung rtsom phyogs bsdus. Beijing: Krung go’i bod rig pa dpe skrun khang, pp. 616-623.

- Petech, Luciano. 1990. Central Tibet and the Mongols — The Yuan- Sa-skya Period of Tibetan History. Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, Rome, pp. 5-25.

- Petech, Luciano. 1993. “P’ags-pa (1235-1280).” In In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yüan Period (1200-1300), edited by Igor de Rachewiltz, et al. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Rossabi, Morris. 1988. Kublai Khan: His Life and Times. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rossabi, Morris. 1983. China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Wylie, Turrell. 1977. “The First Mongol Conquest of Tibet Reinterpreted.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 37, no. 1: 103-133.

- Wylie, Turrell. 1984. “Kubilai Khaghan’s First Viceroy of Tibet.” In Tibetan and Buddhist Studies: Commemorating the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Alexander Csoma de Korös, edited by Lajos Ligeti. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Ye shes rgyal mtshan. N.d. Chos kyi rgyal po ’phags pa rin po che’i rnam par thar pa. No publisher information available.

Source: Dominique Townsend, “Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen,” Treasury of Lives, accessed July 28, 2018, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Pakpa-Lodro-Gyeltsen/2051.

Dominique Townsend has a PhD in Tibetan Studies from Columbia University and is currently teaching at Barnard College.

Published January 2010

Disclaimer: All rights are reserved by the author. The article is reproduced here for educational purposes only.

About Treasury of Lives

The Treasury of Lives is a biographical encyclopedia of Tibet, Inner Asia, and the Himalaya. It provides an accessible and well-researched biography of a wide range of figures, from Buddhist masters to artists and political officials, many of which are peer reviewed.

The Treasury of Lives is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. All donations are tax deductible to the fullest extent of the law. Your support makes their important work possible. For information on how you can support them, click here.

Source: https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Pakpa-Lodro-Gyeltsen/2051. Click on image to enlarge.

Source: https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Pakpa-Lodro-Gyeltsen/2051. Click on image to enlarge.

For more interesting information:

- The Dorje Shugden category on my blog

- The Tsongkhapa category on my blog

- The Great Lamas and Masters category on my blog

- Who is Tulku Drakpa Gyeltsen

- Murder in Drepung Monastery: Depa Norbu

- H.H. the Great Thirteenth Dalai Lama Thubten Gyatso’s prediction

- The 14th Dalai Lama’s prayer to Dorje Shugden

- Danzan Ravjaa: The Controversial Mongolian Monk

- Zaya Pandita Luvsanperenlei (1642 – 1708)

- 10,000 Mongolians receive Dorje Shugden!

Please support us so that we can continue to bring you more Dharma:

If you are in the United States, please note that your offerings and contributions are tax deductible. ~ the tsemrinpoche.com blog team

Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen born in Ngari was the fifth of the Five Sakya leader, the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism. He was credited with having established the foundation of the Sakya tradition. Historical tradition he was remembered by many having a part in the dispute of the Yuan dynasty and vice-king of Tibet. Pakpa had helped incorporate Buddhist rituals into the Yuan court. Pakpa and Khubilai Khan had a close relationship through marriage alliances with his family members. Pakpa’s collected works fill three volumes and he is credited with having developed the theory of Buddhist ruler-ship. Interesting reading the history of it. Phagpa spent his last years in Tibet where he died causes unknown.

Thank you Rinpoche for this sharing.

Pakpa is a very influential lama, and helped to connect the Tibetans to the Mongolians, were a potent military force in their region. Tibetans connections to the Mongolians in the future played an important role of the politics of Tibet eventually. By Pakpa designating Kublai Khan as Manjushri and brought the Yuan Dynasty court closer to Buddhism, could have indirectly stopped much more bloodshed from the side of the Mongolians.

This beautiful painting (thangka) is in Sakya Monastery in Tibet’s protector chapel. It is Dorje Shugden Tanag or Dorje Shugden riding on a black horse. This is the Sakya version of Dorje Shugden. Dorje Shugden is originally Sakya and still practiced in Sakya and came to Gelug and Kagyu practitioners later.

8 pictures of the Sakya Monastery to share, where Protector temple Mug Chung is located. This is the monastery where Dorje Shugden was enthroned first as a Dharma protector in Tibet over 400 years ago by the highest Sakya throneholders and masters. Since then when people are doing Dorje Shugden prayers and pujas, they invoke his holy wisdom presence from Mug Chung Protector Chapel in Sakya Monastery in Tibet.

Thank you Rinpoche for sharing this short biography of Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen. Amazing… Pakpa Lodro Gyeltsen has a very good memory as he can mastered eight volumes of works that he taught and has given oral texts commentary. He would recite the mantras of Avalokitesvara and Manjushri thousands of times each day. He did serve as a teacher to numerous abbots of Gelug monasteries in Lhasa too. Inspiring post of a great master.