The Collected Works of H.H Pabongka Rinpoche

(By Tsem Rinpoche)

Over the decades, you have had various teachers and various individuals and practitioners who really promote, complement, and establish and, at the same time, kind of ‘market’ their particular practice, yidam, lineage, protector, guru, monastery, and meditations. When someone promotes their meditations, or their lineage, or their practice, or whatever they are promoting, you have to look at it with an open mind. Just because they promote something that has been beneficial for them or someone they know, it does not mean they are sectarian or against other things. So, if someone practises, for example, Tara and they promote Tara, they talk about Tara, they explain Tara, they always relate to Tara, and they share and encourage Tara practice with others, does that mean that they are against other Buddhas? It just means that they have a particular attraction to Tara. Similarly, you have the lineage heads, like the Gaden Tripas of the Gelugpas. The Gaden Tripas only teach the doctrines of Lama Tsongkhapa, only teach the practice of Lama Tsongkhapa, and only give transmissions, initiations, and commentaries that are from Lama Tsongkhapa or related masters. So does that mean the Gaden Tripa is sectarian? No, he is the upholder of the Gelugpa tradition. He is the head of the lineage, so of course he is going to promote that. But if he promotes that, would you say that he is sectarian? Are all the 103 Gaden Tripas who have done nothing but promote Lama Tsongkhapa’s lineage for the 600-year history of the Gaden Tripa institution sectarian? That would simply be illogical, wouldn’t it?

Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche was a great meditator, here we see see his stunning hermitage outside of Lhasa, Tibet. Click to enlarge

So if someone loved their country of Japan and they only talked about Japan, does that mean that this person excludes every other country, because we read into this person’s actions that they view all other countries as inferior? Of course not. In Tibetan Buddhism you have the heads of each lineage. For example, the head of the Gelugpas is the Gaden Tripa, the head of the Drikung Kagyupas is the Drikung Gyabgon Rinpoche, the head of the Karma Kagyus is the Karmapa, the head of the Nyingmas switches between high-ranking Rinpoches, and the head of the Sakyas is the Sakya Trizin. As heads of their respective lineage, they promote their lineage’s teachings. For example the Sakya Trizin promotes the Sakya teachings, teaches you the superiority of the 13 Golden Dharmas of the Sakyas, and always highlights the Sakya refuge tree, the Sakya practice, the Sakya commentaries, and everything Sakya. But as Sakya Trizin, the head of the Sakyas promoting the Sakya lineage, does that mean he is biased, schismatic or sectarian against other sects? Of course not.

Similarly, you have great lamas of the Gelugpa practices, such as Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche himself, who had thousands of students from Central Tibet and also Kham; and who had hundreds of students that were high lamas, who became very prominent figures in the religious and political scenes; and also government servants, and nobles and aristocrats, and the very wealthy. Given that he had so many students and thousands attended his teachings in Tibet, naturally there was going to be some jealousy.

Naturally, there was going to be some people who became angry and there was going to be some fault-picking. No matter how much of a perfect teacher you are, there is always going to be someone out there who doesn’t see that, and that will speak up and say something. That is the way the world operates. So for many decades, Pabongka Rinpoche has been falsely accused of being sectarian. And when he is so-called ‘sectarian’, it infers he is against the other sects. But there is no evidence anywhere, from any of his main disciples, his older disciples or any renegade groups that have formed because of his views, which would justify the unfair commentaries against him, labelling him as sectarian. And we can pretty much conclude that it comes down to, more or less, jealousy, envy, and just what famous and very well-known people have to endure, past, present and in the future. That’s what people have to endure.

In fact, Pabongka Rinpoche was often heard, for example as recounted in Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, saying that if you were to disparage any other form of Buddhism, any other school, lineage or practice, it is equivalent to killing 1,000 Buddhas. Of course, it is not possible to kill even one Buddha, because they do not have the karma to be killed, but if it was possible the karmic repercussions would be very heavy. And it would be really damaging for the person committing the act. So speaking badly about any other form of Buddhism is equivalent to killing 1,000 Buddhas. By him saying that, he is discouraging people who practise the mind training teachings, which are very well set out in Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, from being sectarian. He does not encourage sectarianism at all. Therefore, those types of accusations against him are definitely based on his growing and massive popularity.

Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s attainments are of the highest spiritual calibre. Here we see the self-arisen eye of Heruka at Pabongka Hermitage, a testament of his enlightened mind. Click to enlarge.

Other people have said that Pabongka Rinpoche converted other temples to his lineage, and that he had ordered other temples of whatever non-Gelugpa sect to be destroyed or converted or changed. Actually that wasn’t Pabongka Rinpoche’s order or instruction at all. He did have fanatical students. He did have a fanatical manager who was well-known to be very gruff and very rough, and also would do things to promote his lama albeit sometimes in a way that wasn’t very pleasant. He was known for that. Gelek Rinpoche cites that in his commentaries. Basically the assistant did things without the knowledge of the lama, and the lama had to bear the consequences of that, which was, and for some misinformed people still is, a bad name. And people were very afraid, and out of respect for Pabongka Rinpoche they kept quiet about his main manager. This was because his main manager was known to go and slap people who fell asleep during teachings, or was very rough and rude in his mannerisms. People just tolerated him. It is said that it was this manager that used to go around Kham and bully temples and people. So unfortunately it was not Pabongka Rinpoche’s instruction at all, but the blame came to Pabongka Rinpoche.

Joona Repo in his Phabongka Dechen Nyingpo: His Collected Works and the Guru-Deity-Protector Triad talks about the issues surrounding Pabongka Rinpoche. On Page 6 and 7 of his work, he states that there was indeed some discord, that there were some accusations of sectarianism. But what I like about what Repo is saying is that he is not taking sides, he is presenting the information and he is letting us come to our own conclusion. His information is very unbiased and very straightforward, although he quotes from other sources that may seem a little biased. But it is the same in any human interaction. There are going to be people who are biased, there are going to be people who are pro and against. That is the way the ball bounces. But definitely Pabongka Rinpoche was not sectarian at all.

Overall, his work is a very interesting commentary. On Page 10, you can see his section on the collected works of Pabongka Rinpoche. There are 11 large volumes of extensive writing and if you go towards the end of his work, which is around Page 43 and onwards, you will see a list of the 11 volumes of work that Pabongka Rinpoche composed, and each chapter, which is incredible. He wrote extensively on Vajrayogini and after Vajrayogini, he wrote extensively on Heruka and Yamantaka practices, and many, many other practices. So in between his teaching schedule, his retreats, his meditations, his travels to give teachings at the request of many monasteries, and also being the root lama of very many high lamas such as Taktra Rinpoche, Trijang Rinpoche and Ling Rinpoche, he also found time to pen down so many incredible works and writings that equal to 11 volumes if following the Delhi edition, 12 volumes if following the Lhasa edition. The last volume of the Lhasa edition was misplaced so it wasn’t carried into India. But whatever it is, either 11 or 12, it is a lot. And they are very extensive.

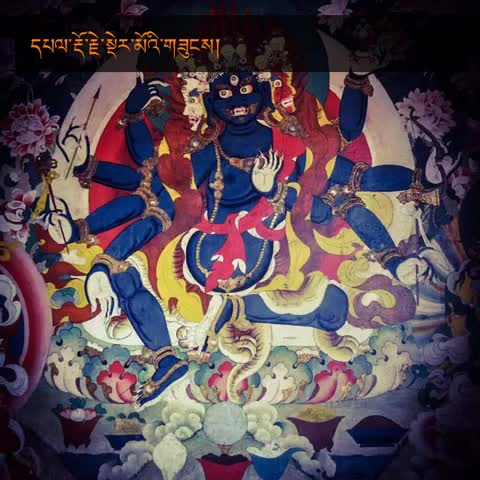

An exquisite old thangka of Heruka Cakrasamvara along with the four main dakinis of his entourage. Click to enlarge.

Pabongka Rinpoche’s work is seminal and it’s incredible that a “slow”, “not very bright”, “second rate” Lingse Geshe can come out with all these writings. Because, as you know, when Pabongka Rinpoche was in the monastery, no one had hope that he would amount to anything. He was considered very slow and not very bright; he didn’t get the teachings and he never received a Geshe Lharampa degree, he got a Lingse degree. Lingse is just a degree because you passed, it is not because you did well. You just have to graduate because you have finished your term. Nobody thought highly of him, no one looked at him, and he wasn’t even high ranking. For someone that was not high ranking, for whom no one had hopes for and was not backed up by much, and also did not do well in his studies (it seems), he came out to be the lama of all lamas. And he came out with 11 volumes. That just shows you his incredible qualities.

If you look at the breakdown of each of the 11 volumes, at the kind of works he wrote, some are just incredible, and many are tantric in nature. But you have to understand, if it is tantric in nature, you have to understand the sutras very well to be able to understand the tantras. After all, they are interconnected, and the sutras are the basis of tantras. Without sutric understanding, tantric understanding would be very much stifled. So to see his writings on tantra and so extensive, especially on more of the subtle meditations of Heruka, Yamantaka, and Vajrayogini’s practice, would tell you that he has an extensive, if not attained, grasping of the subject matter. And what I mean by attained is someone writing from having reaped results from the meditation and commentating on the existing works on those deities to further elucidate what has already been written, so that future practitioners will have an easier path, and easier go at it.

It says on Page 12 that he has written extensively on Heruka, whose other name is Chakrasamvara. It also says he has written extensively on the solitary practice of Vajrayogini Naro Kacho, or Naro Kechari. He has written their abbreviated sadhanas, the ganachakra texts (tsok), the self-entry ritual (daju), the burning offering (jinsek) and, incredibly, the transference of consciousness instructions, which is how to transfer our consciousness into Kechara Paradise at the time of death. It says clearly that Pabongka Rinpoche wrote many individual texts on Vajrayogini, more than any other deity, although Yamantaka and Chakrasamvara, or Heruka, comes in at a close second. So that would tell how Pabongka Rinpoche’s heart was very close to the Vajrayogini practice. And at the same time, how he would leave these writings for future generations, which would denote his emphasis on the practice of Vajrayogini and its efficacy. Because if this practice was not efficacious or beneficial, or if we were running out of the karma for it to benefit us, then he would not writing so extensively on such a practice.

After all, it is considered by the greatest scholars of his day that Vajrayogini practice was one of the heart and secret practices of Lord Tsongkhapa himself. It is very beautiful because Pabongka Rinpoche himself, in his 11 volumes of his works and writings, focused very much on Vajrayogini first and secondly on Heruka Chakrasamvara and Yamantaka, while his heart disciple, Trijang Rinpoche, in his own collected works wrote predominantly and very much on the Cittamani Tara set of teachings. And that was very complementary.

Particular to note, it says on Page 23:

“Another text that does not appear to have been included in the original Lhasa edition of the Collected Works, its later reproductions and reprints, the Delhi Supplement, or the Potala edition, is a new initiation ritual manual composed by Phabongkha for the Thirteen Pure Visions of Tagphu (stag phu’I dag snang bcu gsum), also known as the Thirteen Secret Dharmas (gsang chos bcu gsum) or Thirteen Secret Visions (dag snang gsang ba bcu gsum). These “Thirteen Secret Dharmas” refer to a cycle of visionary teachings originating from Tagphu Tulku Lobsang Chokyi Wangchuk (stag phu sprul sku blo bzang chos kyi dbang phyug, 1765 – c.1792) and transmitted through his incarnation lineage, down to Tagphu Pemavajra and from him to Phabongkha. The cycle contains practices of deities such as Amitayus, Vajravarahi, Hayagriva, Avoliteshvara and, most importantly, Cittamani Tara”

– Joona Repo, “Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo: His Collected Works and the Guru-Deity-Protector Triad”, Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, no. 33, October 2015, p.23.

So it’s very interesting that Pabongka had written about these 13 great visions, which is extremely rare. Mind you, Tagpu Rinpoche was not considered a scholar, not very learned, not highly sought after, and not a high-ranking lama in any way. Yet, he had constant or consistent visions of Tara and he was moist with the practice of meditation. He was able to compose great teachings from his visions that were passed down to Pabongka Rinpoche, and from Pabongka Rinpoche to his disciples. From there it totally pervaded the Gelugpa world. What is interesting is that the teachings that are very pervasive in the Gelugpa world that came from the 13 Pure Visions of Tagpu Rinpoche do not stem from Tsongkhapa, and do not stem from the historical Buddha. Yet, the teachings are placed on the level of those taught by Tsongkhapa and Buddha. For example, the Cittamani Tara Anuttarayoga Tantra set of teachings, practice, meditations, and path are very, very highly regarded within the Gelugpa school of Buddhism. They are highly practised and promoted within the Gelugpa. And many of the senior monks of Gaden, Sera and Drepung Monasteries would have had the initiation of Cittamani Tara, which originally came from the vision of Tagpu Rinpoche, who was actually just a normal lama in a small village, who really was not a scholar or well-known for anything. But, you can see that within the Gelugpa school of Buddhism, there are people who are regarded to have true visions. What comes to such masters in visions are highly regarded, and practised because they bear results over time.

As it says on Page 25:

“Shugden, as is obvious from the epithets that Phabongkha used in relation to the deity: “Protector of Lord Manjushri [Tsongkhapa’s] Teachings (‘jam mgon bstan srung)” and “Protector of the Virtuous [Gelug] Teachings (dge ldan bstan srung)”, was indeed considered by Phabongkha as an important protector of the Gelug tradition. Without Phabongkha’s efforts and writings based on the revelation of the cycle by Tagpu Permavajra, the cult of the deity would most likely not have become widespread as it is today. Yet, based on what we can deduce from his Collected Works, did Phabongkha lead a “charismatic movement”, or similar, centred on Shugden, Vajrayogini and himself as a sacred triad of esoteric Gelug doctrine, as Donald Lopez suggests?”

– Joona Repo, “Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo: His Collected Works and the Guru-Deity-Protector Triad”, Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, no. 33, October 2015, p.25.

Now, what it is saying here is the epithets that Pabongka Rinpoche used in his writings on Dorje Shugden kind of tells you his feelings on Dorje Shugden. And the epithets are, for example, ‘Jamgon Tensung’ in Tibetan which means ‘Protector of the Virtuous Teachings’ or ‘Protector of the Virtuous Gelug Teachings.’ And that is a very high epithet that you would give to a so-called ‘worldly’ protector. So therefore the label or the honourific title that Pabongka Rinpoche attached to Dorje Shugden’s name tells you very clearly how he felt about Dorje Shugden. To Pabongka Rinpoche, Dorje Shugden was not an ordinary or lowly protector and at the same time in that way, we shouldn’t think that it is because of Pabongka Rinpoche that Dorje Shugden became very big. That is a misunderstanding. Dorje Shugden was already big before Pabongka Rinpoche’s time and it was practised widely, even within the Sakyas, and disseminated within the Sakyas, among the few throneholders who very much promoted Dorje Shugden’s practice. Pabongka Rinpoche didn’t promote Dorje Shugden because in his 11 volumes, he only had a few writings on Dorje Shugden, perhaps because there was a lot of work out on Dorje Shugden already. But having said that, whatever he did write and the titles he accorded to Dorje Shugden would tell you the deep respect he had for this deity, due to observation, reading, study, writing and perhaps the visions of his lama. Perhaps it was his lama who told him the nature of Dorje Shugden. As we know, Tagpu Rinpoche went to Gaden Heaven directly to receive the lineage of Dorje Shugden from Duldzin Drakpa Gyeltsen and Tsongkhapa themselves. So this is a very important point to remember. If the Gelug world can accept the Cittamani teachings of this lama that arose from his visions of Tara, why can’t everyone accept the teachings and lineage of Dorje Shugden that arose from the same lama and his visions when in Tushita heaven? After all, the Cittamani lineage and teachings are practiced by the most highest Gelug lamas if not all, and this teaching did not arise from Tsongkhapa or the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. Cittamani arose from Tagpu Rinpoche’s visions. So the teachings within the Gelug lineage do not all need to arise from Tsongkhapa or the historical Buddha directly. This is just like in the Nyingma lineages, who have many teachings that arose from hidden treasures (termas) that were found by leading Nyingma masters but not necessarily directly from the historical Buddha.

Page 27 is very interesting because you have a great scholar by the name of Tuken Lobsang Chokyi Nyima who lived, according to Repo, between 1737 and 1802. This scholar had written life-entrustment rituals for the five forms of Pehar, which is Nechung. And in this he describes that they are manifestations of Hayagriva. The funny thing is, when a protector is worldly, they give you a life-entrustment or sogtae, and when a protector is enlightened, they give you an initiation into the deity. So the distinction here is between worldly forms, which entail life-entrustment, and enlightened forms, which entail initiation. For example, when you do the practice of Four-Faced Mahakala (Caturmukha) who is in enlightened form, they give you initiation. But when you do Setrap, the Five Sisters, the Five Pehar Gyalpos or Dorje Shugden, it is life-entrustment. So life-entrustment would denote that they are in worldly form, and initiation would denote that they are in enlightened form. Having said that, Trijang Rinpoche said that the Five Gyalpos are the forms of the Five Dhyani Buddhas, and the scholar Tuken Lobsang Chokyi Nyima said that Pehar is actually an emanation of Hayagriva. It is generally believed that Setrap is an emanation of Buddha Amitabha, still practised by Gaden Shartse Monastery up till today. What is interesting is to say that based on the fact that Dorje Shugden has a life-entrustment ritual (rather than an initiation) proves him to be an unenlightened worldly deity is false, because the five forms of Pehar also have a life-entrustment, the Five Sisters also have a life-entrustment, and Setrap also. Pehar, as we know, is the main protector of the Tibetan government and one of the protectors of the Dalai Lama. So are people saying that they are practising a worldly deity that is not enlightened? Therefore to use the fact that these protectors have life-entrustment rituals is not proof that these deities are worldly and not enlightened.

We can see that some people say that Vajrayogini was not very popular prior to Pabongka Rinpoche but that is not true. There is much evidence to show Vajrayogini being very pervasive within the Gelugpas and the Sakyas prior to Pabongka Rinpoche. Even the great Chinese Emperor Qinglong was known to have been initiated into the Vajrayogini and Chakrasamvara’s practices.

We can see on Page 30, according to Repo’s research:

“Vajrayogini, as has already been noted, was already a very popular deity amongst a number of highly influential eighteenth century scholars such as Tuken, who wrote on the practice extensively. More importantly it is clear from the works of these scholars that Vajrayogini was already considered by a number of leading teachers as the “un-common secret dharma hidden in the mind” of Tsongkhapa, i.e. his secret meditational deity.”

– Joona Repo, “Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo: His Collected Works and the Guru-Deity-Protector Triad”, Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, no. 33, October 2015, p.30.

What this means is that Vajrayogini was one of Tsongkhapa’s main practices. He hid it from the public because the practice is so sacred and so sensitive that it required it to be hidden. Most tantric teachings, if not all, are required to be practised in secret. But Vajrayogini is secret among the secret. And the more secret you practise, the easier it is to gain the attainments.

It is definitely not Pabongka Rinpoche who elevated Vajrayogini and Dorje Shugden and made them popular, as people would like to say. But they were already popular prior to Pabongka Rinpoche’s writings and proliferation of these practices. Obviously, Pabongka Rinpoche proliferated these practices not for his personal gain, as he already had his practices; it was more for the benefit of his students and future students to come. You can read this carefully in Repo’s commentary on Page 31. Please take special note of that.

Pabongka Rinpoche’s personal practice, which he related to Ribur Rinpoche, for four hours a day, was the Guru Puja in conjunction with Chakrasamvara. This is the Guru Puja practice composed by the great 1st Panchen Lama, Lobsang Chokyi Gyeltsen. So Pabongka Rinpoche spent four hours a day engaging in Guru Yoga practice, which is in the Guru Puja. That was his main practice and his main daily meditation to gain attainments. That is listed on Page 36. This tells you something about Pabongka Rinpoche’s mind, that he was very devoted to his guru and through this devotion he gained very high accomplishments.

On Page 39 in Footnote 93, you can also see that His Holiness the great 10th Panchen Lama, Chokyi Gyeltsen, also composed a fulfilment ritual to Dorje Shugden. So not only did the 10th Panchen Lama practise Dorje Shugden but he also composed texts, adding to the growing amount of teachings available on this protector. Here, we are not talking about local small-town lamas; we are talking about one of the highest lamas of Tibet who was well-known to be very well-attained and scholastic, and who also not only practised Dorje Shugden but also composed texts.

So overall, the commentary given by Repo is very unbiased, from which we can learn a lot, and one that gives you insight into Pabongka Rinpoche. He writes in a manner that is not for or against, but very eye-opening, telling you the character of Pabongka Rinpoche. We can conclude Pabongka Rinpoche to be non-sectarian and very learned, and although outwardly he showed some sort of slow student syndrome, he produced the greatest teachers, the highest ranking lamas, the most influential lamas who were all his disciples. At the same time he came out with 11 volumes of extant teachings on various subjects. This is indeed a very interesting commentary to read by Joona Repo, and I highly recommend everyone to read it very carefully.

Tsem Rinpoche

There is a famous story of how Heruka actually appeared to Pabongka when he visited Cimburi in Tibet, where there is an image of Heruka. This is where the Blood drinker’s mountains are and this name refers to Heruka – Drinker of Blood. Apparently, Pabongka went to this place three times during his lifetime. When he first went there, this image spoke to him, opened its mouth and a tremendous amount of nectar came out. Pabongka collected the nectar from the mouth of Heruka while in the presence of sixty or seventy people. This nectar was then made into nectar pills. The Gelugpa’s current nectar pills originate from there. It is also stated that this very same cave in Cimburi where Pabongka received the nectar from the Heruka image was the place where Heruka promised him the following: “From now on, for the next seven generations, whoever practices my teaching, I will protect and help.”

Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo: His Collected Works and the Guru-Deity-Protector Triad

His Holiness Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche is one of the greatest Tibetan Buddhist masters of the recent past. It is through his efforts in meditation, learning, and teaching that the core teachings of the Gelugpa tradition were preserved and passed down for future generations. There isn’t a Gelugpa master alive today, who is not connected to Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche in one way or another, such as belonging to either his sutric or tantric lineage, or having read or studied his many works.

Most famous for his experiential exposition of the Lam Rim, called Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, Pabongka Rinpoche’s holy legacy has permeated the entire lineage. In the work presented below, Dr. Joona Repo, from the University of Helsinki, Finland, provides an academic view of the life of Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche, and the Buddhist ideal that the guru, yidam and protector are one and the same, working together so that the practitioner is able to gain spiritual attainments and ultimately, enlightenment. The article published in Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, a bi-annual journal published by Le Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (the National Centre of Scientific Research) in Paris, is particular noteworthy.

Given the current misconceptions about Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche due to the ban on Dorje Shugden and the ensuing controversy, Dr. Joona Repo seeks to provide a much broader perspectives of the teachings and practices that Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche held and taught through examining his Collected Works. It is through the Collected Works that we come to understand that the accusations against Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche being a revisionist of the Gelug tradition is false. In fact we come to understand that Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche upheld the already established beliefs, teachings and practices within the Gelug tradition. In doing so he was a great master who upheld the traditions stemming from Lama Tsongkhapa. Please enjoy reading this great article that sheds light and dispels the darkness of misconception.

Click here to download the PDF file.

Credits: Joona Repo, http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_33.pdf

Credits: Joona Repo, http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_33.pdf

Credits: Joona Repo, http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_33.pdf

Credits: Joona Repo, http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_33.pdf

Credits: Joona Repo, http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_33.pdf

Credits: Joona Repo, http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_33.pdf

Credits: Joona Repo, http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_33.pdf

Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo:

His Collected Works

and the Guru-Deity-Protector Triad[1]

Joona Repo

(University of Helsinki)

Fully complete mandala of love [Jampa (byams pa)] and compassion,

Crowning ornament of the holders of the teachings [Tenzin (bstan ‘dzin)],

the source of bliss, The manifestation of your activities [Trinle (‘phrin las)] pervades the earth,

[You are the] lord of an all-pervading ocean [Gyatso (rgya mtsho)] of victors![2]

The above verse, which in the Tibetan weaves within it the names of the teacher it praises, Phabongkha Jampa Tenzin Trinle Gyatso (byams pa bstan ‘dzin ‘phrin las rgya mtsho, 1878-1941), also known as Dechen Nyingpo (bde chen snying po), are attributed to Gendun Choephel (dge ‘dun chos ‘phel, 1903-1951). The praise (bstod bsngags) was composed as an inscription (rgyab yig) to a drawing that Gendun Choepel made of the teacher, and demonstrates the high esteem in which Phabongkha was once held by one of the most forward-thinking Tibetan figures of the early twentieth century. The writings of Phabongkha contained within his Collected Works (gsung ‘bum) are today widely available in eleven volumes, together with a supplementary volume. The subjects of Phabongkha’s writings, and of his immediate teachers and students are diverse, reflecting both the conservative continuation of Tsongkhapa’s (tsong kha pa, 1357-1419) Gelug (dge lugs) tradition as well as a unique development of the same. Central to his teachings and writings were those of the Stages of the Path (lam rim) genre exemplified by his most famous teaching, Liberation in Your Hand (rnam grol lag bcangs)[11.1].[3] These were then supplemented at more advanced levels by tantric practices, which form the bulk of Phabongkha’s Collected Works, with an emphasis on the secret teachings of the Gelug tradition’s orally transmitted Ganden Hearing Lineage (dga ldan snyan brgyu), as well as a number of newer revealed teachings, or “pure visions” (dag snang).

Phabongkha is undoubtedly a highly contested and perhaps often misunderstood historical figure. As an important lineage holder of the Dorje Shugden (rdo rje shugs ldan)-cycle of teachings within the Gelug tradition, he has been reviled as a sectarian spirit-worshipper by some and lauded as a pivotal guardian and interpreter of Tsongkhapa’s lineage by others. The controversy surrounding the deity, who has today been abandoned by most Gelugpas, has already been documented in several important seminal studies by scholars such as Georges Dreyfus and Donald Lopez and thus this article will not touch upon these contemporary issues and developments.[4] Numerous publications produced by both sides of the heavily polarized debate also exist, however within this article I have largely avoided critiquing or analyzing these, even with regard to accounts of Phabongkha. The historical facts and arguments presented by both are often far too overshadowed by a clearly biased agenda and interpretation or a general lack of usage or citation of Tibetan textual sources, resulting in inaccuracies too numerous to address here.[5]

Phabongkha, due to his promotion of Shugden, is often blamed for attacking the Bon (bon) tradition and formenting sectarian discord against the Nyingma (rnying ma) lineage, especially in Kham (khams). It remains, however, to be established whether he was personally responsible for ordering any violent or sectarian acts or not, or if these were instead instigated and carried out independently by zealous extremist students.[6] Certainly many of Phabongkha’s students and followers from the period, and many modern Gelug teachers, hold the view that Phabongkha has been unfairly accused.[7] Thus although they do not deny that cases of sectarian discord may have taken place, they are adamant that these were not instigated or ordered by Phabongkha himself, who they say was a victim of baseless accusations due to his growing popularity.[8] Phabongkha’s direct role with regard to these unfortunate events thus remains unclear due to the lack of unbiased or independent accounts.

Phabongkha certainly held strong views and did not hold back from expressing them. He strongly believed that Tsongkhapa possessed a superior interpretation of the Buddhist path, especially with regard to Madhyamaka. However, whether or not he was uniquely sectarian when considering historical Tibetan religious figures as a whole is arguable, especially as his written works present both cases of polemical attacks on other traditions, while at other times stating the importance of being non-sectarian.[9] Far more research is certainly needed for us to have a clearer understanding of not only Phabongkha’s views of other sects, but also about the sectarian discord that took place in the eastern parts of Tibet. What is definitely unique, however, is how this Gelug-protectionism manifested in the belief that Shugden would specifically shield the lineage from being “corrupted” (log par spyod pa) by “the views and tenets of others” (gzhan phyogs pa’i lta grub) through engaging in often very wrathful activities.[10] Thus apart from the usual functions of a protector, Shugden perhaps also became an attractive deity-figure for those disposed to sectarianism.

Due to the contested nature of Phabongkha’s legacy amongst Tibetan Buddhist practitioners, it is perhaps impossible to empirically present a face of Phabongkha that will satisfy everyone. The current controversy is so polarizing that it has led to a distortion of facts from many different sides, especially in regards to what Phabongkha’s actual teachings consisted of. These strong and varying views of Phabongkha are certainly rooted in faith and the tantric interpretation of guru-devotion, which demands unfailing loyalty to one’s own teachers and their interpretations and presentations of their lineage history.

This article is not concerned with interpreting, refuting or defending Phabongkha’s views of other traditions or even with Shugden per se. Instead it aims at presenting an alternative view of Phabongkha’s works and what Phabongkha considered, or rather what he didn’t consider, as the central emphasis of his teachings. Lopez writes about Phabongkha, that:

“Under his influence something of a charismatic movement occurred among Lhasa aristocrats and in the three major Geluk monasteries in the vicinity of Lhasa…, with Vajrayogini as the tutelary deity (yi dam), Shugden as the protector, and Pha bong kha pa as the lama”.[11]

Through introducing and demonstrating the variety and richness of material composed by Phabongkha, this article will present a different view from this often-repeated and held perception, which is certainly an over-simplification, even if Phabongkha did undoubtedly play a seminal role in the dissemination of the practices of Vajrayogini and Shugden in the twentieth century.[12] I will suggest that Phabongkha’s vision was not a simplified trinity, or a revisionist presentation of Tsongkhapa’s practice lineages, as is often claimed or suggested. Shugden and Vajrayogini were part of a wider program, became elevated in importance, but they did not displace or relegate other practices to a lower status, or form a central pool of practices. Although the opposite may be true today in the case of several Gelug or Gelug-derived lineages which claim to follow Phabongkha’s lineage, this does not necessarily mean that this was the situation during Phabongkha’s lifetime, or in line with his original intentions.

Much information remains to be uncovered about Phabongkha, the understanding of whom this article hopes to make a small contribution to. Indeed how can we presume to understand such a significant historical figure from the very limited published research available today? In order to demonstrate that Phabongkha’s emphasis in terms of religious practice lay not only with Shugden and Vajrayogini, this article will also begin with a brief history of the compilation and a discussion of the rich variety of literature produced by this teacher as embodied in his Collected Works, which is often ig- nored or overshadowed by the emphasis placed on the authors’ Shugden-related works. It should be noted that considering the breadth of Phabongkha’s works and the topic, the current article can only present an extremely brief introduction to his Collected Works, which will also be compared to the contents of the collected works of his closest student, Trijang Rinpoche Lobsang Tenzin Gyatso (khri byang rin po che blo bzang ye shes bstan ‘dzin rgya mtsho, 1901- 1981). This brief presentation of these works will serve as a basis for the rest of the article and particularily its discussion of Vajrayogini and Shugden. Finally, the full contents of the Collected Works and the supplementary volume are listed and translated into English in the Appendix. The presentation of the contents in English will allow non- Tibetan readers a chance to browse the titles attributed to this im- portant twentieth-century teacher as well as clearly demonstrate the breadth of Phabongkha’s work.[13]

Phabongkha’s Collected Works

Phabongkha’s Collected Works in their two most widely available forms are: a reproduced edition published by Chophel Legdan in the 1970s in Delhi and the original Lhasa (lha sa) woodblock edition made available through the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (TBRC), both of which make up eleven volumes (see Appendix).[14] A supplementary volume was also later added to the Delhi edition.[15] The Lhasa edition of the eleven volume set comprises of 122 separate titles, a number that could be expanded if several smaller works subsumed under one title are taken into account. For example the second work of the sixth volume (cha), A Collection Regarding the Sadhanas of the Highest Deities such as “Guide to the Lifespan of Kurava” and Other Easy-to-Perform Recitation Practices [6.2], is composed of ten sadhanas of various deities.[16] Furthermore a number of Phabongkha’s compositions are today also missing from both the Delhi and Lhasa editions, as will be shown below.

Included in the Collected Works are teachings and notes on philosophical topics such as pramaṇa (valid cognition), records of teachings he received, his correspondences, advice and even a biography he composed of his principal teacher [10.1], Dagpo Lama Lobsang Jamphel Lhundrup Gyatso (dwags po bla ma blo bzang ‘jam dpal lhun grub rgya mtsho, 1845-1919). Thus, the contents represent a variety of written materials which bring together not only Phabongkha’s own writings, but also works and notes on Phabongkha’s life, activities and teachings. The most famous example of a text penned by his students based on his oral discourses is Liberation in Your Hand [11.1], a teaching of Phabongkha’s compiled and edited by Trijang Rinpoche, and which takes up the entire eleventh volume (da) of the set.

On top of Liberation in Your Hand, around ten other Stages of the Path -related titles are listed in the contents of the Collected Works and the Delhi supplement, including instructions on the preliminary practices of the Stages of the Path (lam rim sngon ‘gro sbyor chos) [5.2, 5.3], an important set of explanations on the Four Interwoven Annotations of the Great Stages of the Path (lam rim chen mo mchan bu bzhi sbrags ma) [5.1] and a commentary on a combination of both Panchen Lobsang Yeshe’s (paN chen blo bzang ye she, 1663-1737) Swift Path Stages of the Path (lam rim myur lam) text and Tsongkhapa’s Middling Stages of the Path (lam rim ‘bring ba)[9.4].

The majority of Phabongkha’s works, however, concern tantric topics, ranging from subjects such as chod (gcod), for which he composed a text that is still used widely today by Gelug chod practitioners [5.10], to quintessential guru yoga texts. In terms of the latter, Phabongkha created an expansion of Panchen Lobsang Chokyi Gyaltsen’s (paN chen blo bzang chos kyi rgyal mtshan, 1570-1662) Six-Session Guru Yoga (thun drug bla ma’i rnal ‘byor) [9.3] manual and, for example, composed a secret variant of the standard Gelug guru yoga practice, Hundred Deities of Tushita (dga’ ldan lha rgya ma) [2.9], as well as a related transference of consciousness (‘pho ba) practice [2.11]. The Guru Pūja (bla ma mchod pa), another essential guru yoga text that is particularly central to the Ganden Hearing Lineage, likewise received Phabongkha’s attention. The text was used as a basis for the composition of, for example, a long-life ritual [2.6] as well as a unique rendition of the text focused on the deity Cakrasamvara [2.3].

The cycle of teachings related to Cakrasamvara was the single most important subject of Phabongkha’s writings. For example, one of Phabongkha’s additions to Chokyi Gyaltsen’s Six-Session Guru Yoga text was the inclusion of sixteen lines of praise to Cakrasamvara and his consort, Vajravarahi.[17] While most of Phabongkha’s writings on Cakrasamvara focus on the body mandala practice of the Ghaṇṭapa Lineage, he also composed texts on other forms of the deity, most notably the White Cakrasamvara long-life practice [3.13- 15], an uncommon transmission intimately connected to the Ganden Hearing Lineage and originating from Tsongkhapa’s vision-based Dharma Cycle of Manjusri (‘jam dbyangs chos skor), received via his teacher Lama Umapa Pawo Dorje (bla ma dbu ma pa dpa’ bo rdo rje, c.14th century).[18]

The majority of Phabongkha’s compositions on the Cakrasamvara cycle, however, relate to Vajrayogini Naro Kechari, a form of Cakrasamvara’s consort Vajravarahi. His compositions on the solitary female deity comprise a complete corpus of ritual texts including long and abbreviated sadhanas [4.1, 4.2], several gaṇacakra texts [4.1, 4.12], a self-entry ritual (bdag ‘jug) [4.3], burning offering (sbyin sreg) ritual texts [4.6-8, 4.10, 4.13], transference of consciousness instructions [4.14] as well as an important commentary on the generation (bskyed rim) and completion stages (rdzogs rim) [10.5]. Indeed Phabongkha wrote more individual texts on Vajrayogini than any other deity, although Vajrabhairava and Cakrasamvara come in close second. Cakrasamvara was apparently the principal practice of the lineage holders of the Southern Stages of the Path Lineage (lho rgyud lam rim), a Stages of the Path transmission which was not very widely practiced in Central Tibet and which Phabongkha had presumably received from Dagpo Jamphel Lhundrup.[19] This reason may well have contributed to Phabongkha’s devotion to the Cakrasamvara cycle.

It is interesting to note that although Phabongkha mentions Cakrasamvara, Guhyasamaja and Vajrabhairava, the three principal meditational deities promoted by Tsongkhapa, numerous times in his Liberation in Your Hand, Vajrayogini appears to get no mention. Phabongkha’s teachings that were subsequently transcribed by Trijang Rinpoche, eventually to be published as Liberation in Your Hand, were given in 1921. By this time Phabongkha was already enthusiastic about transmitting Vajrayogini teaching as is evident from his biography, The Melodious Voice of Brahma (tshangs pa’i dbyangs snyan), and the colophons of some of his texts. The colophon of Phabongkha’s Vajrayogini self-entry text, Festival of Great Bliss (bde chen dga’ ston), mentions that Phabongkha gave a teaching on the deity in 1910.[20] As is also mentioned in Phabongkha’s biography, at that time Lady Dagbhrum Jetsunma Thubten Tsultrim Drolkar (dwags b+h+ruM sku ngo rje btsun ma thub bstan tshul khrims sgrol dkar, d.u.) and one of Phabongkha’s managers (phyag mdzod), Ngawang Gyatso (ngag dbang rgya mtsho, ?-1936), both requested him to edit several Vajrayogini texts. Ngawang Gyatso requested for him to review a mandala-rite from the Ngor lineage (ngor mkha’ spyod sgrub dkyil) and Lady Dagbhrum, who wanted to produce new printing blocks of a Shalu commentary on Vajrayogini (zhwa lu khrid yig), requested Phabongkha to edit this.[21] Although a date is not given, the colophon of the Festival self-entry further adds that Lady Dagbhrum also later requested a new self-entry text to be written.[22] This tells us that the daily sadhana practice associated with the deity, Swift Path to Great Bliss (bde chen nye lam), was already composed before this, as it forms a basis for the self-entry text and indeed both the Swift Path and Festival are mentioned together in Phabongkha’s biography, in connection with this story.[23]

Phabongkha’s controversial Shugden material is all collected into the seventh volume (ja) of the set. The specific cycle of teachings associated with Shugden that Phabongkha taught to his students was believed to be based on the pure visions (dag snang) of his teacher, Tagphu Pemavajra Jamphel Tenpai Ngodrub (stag phu pad ma ba dzra ‘jam dpal bstan pa’i dnogs grub, 1876-1935), more commonly known as Tagphu Dorjechang (stag phu rdo rje ‘chang). Tagphu Pemavajra is believed by practitioners of this deity to have travelled to the pure land of Tuṣita and received the complete cycle of teachings related to this protector from Tsongkhapa and Duldzin Dragpa Gyaltsen (‘dul ‘dzin grags pa rgyal mtshan, 1357-1419).[24] The lineage then passes on to Phabongkha and then to Trijang Rinpoche, who then spread this even more widely throughout the Gelug tradition.

Interestingly, out of the complete collection of Phabongkha’s writings, only five are concerned exclusively with the propitiation of Dorje Shugden: two texts related to the life-entrustment (srog gtad) [7.11, 7.12], or rather life-initiation (srog dbang), of the protector, an extensive and middle-length fulfillment ritual (bskang chog) [7.14, 7.15] and a presentation of related explanations and ritual activities [7.13]. Fulfillment rituals are the central practices of Shugden, as they are of other protectors, and function to bond the practitioner with the fierce deity and to exhort them to fulfill their role as guardians of the Buddhist teachings. A brief libation (gser skyems) is also included under a title that incorporates practices of several deities [7.10]. Phabongkha’s actual contribution to the body of Dorje Shugden literature was therefore relatively small when compared to those of his students, specifically that of Trijang Rinpoche, who carried on Phabongkha’s lineage by composing nine separate texts uniquely devoted to the protector. This is fractionally a far larger amount considering that Trijang Rinpoche’s Collected Works, according to the content pages of the volumes, comprise of only sixty-eight titles.[25] Although this numerical comparison certainly gives us a rough idea of the relative amounts of Shugden texts composed by these authors, it is also important to bear in mind that Trijang Rinpoche, in the colophons to his Shugden works, in keeping with the concept of lineage in Tibetan Buddhism, often cites Phabongkha as the source of the teachings which form the basis of his writings. It is unlikely, however, that the various texts were placed whimsically within the two collected works. Instead, I would suggest, the process was very much informed by those works that were actually composed, either orally or in writing, by the teacher whose collected works they were placed inside of.

Trijang Rinpoche’s works combine with Phabongkha’s to create a comprehensive set of Shugden ritual texts. All of these texts are contained within the fifth volume (ca) of Trijang Rinpoche’s Collected Works, which is almost completely devoted to Shugden, although an offering and invocation ritual of Namkha Bardzin (nam mkha’ sbar ‘dzin) who is linked to Shugden’s retinue and is a protector of Dungkhar Monastery (dung dkar dgon) in Dromo (gro mo), is also found, along with the method for performing a life-energy ransom (srog glud gtong tshul) ritual of Hayagriva.[26] Trijang Rinpoche’s works on Shugden include a number secondary ritual texts, for example burning offering rituals related to pacification, controlling, increasing and wrathful activities. He also composed several instructions on the preparation of supporting (rten), protective (bskyang) and repelling (bzlog) thread-cross structures of the deity (mdos). These include associated ritual recitations and drawings of Shugden’s manifestations, retinue and other related paraphernalia needed for the construction of the supporting thread-cross structure (rten mdos). Perhaps his most important work on Dorje Shugden, however, was Music Delighting an Ocean of Oath-Bound Protectors (dam can rgya mtsho dgyes pa’i rol mo), a descriptive text on the activity of the deity that also includes a history of his previous incarnations.[27]

While the two main deities focused on in Phabongkha’s Collected Works were Cakrasamvara and Vajrayogini, the two main deities on which Trijang Rinpoche’s Collected Works focus are both pure vision teachings stemming from the Tagphu incarnation lineage: Shugden and Tara. The Tagphu incarnations were famed as mahasiddhas and were believed to have a close relationship to Tara, especially in her Cittamani, or “Heart-Jewel”, form. Trijang Rinpoche himself received the initiations into the practice of the Cittamani Tara cycle not only from Phabongkha but also directly from Tagphu Pemavajra.[28] While Phabongkha is included as a lineage holder of this practice, his Collected Works in their current widely available format only contain one single stand-alone work on the deity, Garland of Cittamani (tsit+ta ma Ni’i do shal) [3.16], a commentary on the generation and completion stages. Trijang Rinpoche’s Collected Works, however, devote eleven titles to Cittamani Tara, which, as is the case with his Dorje Shugden works, together form a comprehensive set of ritual texts to comple- ment Phabongkha’s contributions and those of past Tagphu incarnations.

Trijang Rinpoche’s Cittamani works include a burning offering ritual, a ganacakra text, extensive and brief versions of the four- mandala offering and a self-entry ritual amongst others. In the colophon to a set of instructions on how to engage in the Cittamani approximation retreat (bsnyen pa) and its preliminary rituals, Trijang Rinpoche notes that this text, which he composed, is based on the works of various teachers, including Phabongkha’s instruction manuals on the generation stage of the deity, of which he says there are two, one presumably being the Garland of Cittamani.[29] Thus, as a continuation of a type of successive lineage effort, it was Trijang Rinpoche who brought to completion the textual cycles of these two visionary cycles received from the Tagphu lineage, although Gelug teachers before both Trijang and Phabongkha Rinpoche had already composed works on the two deities concerned.[30]

Finally, as noted earlier, although here the focus has been on Phabongkha’s guru yoga and tantric texts, Phabongkha also taught and authored extensively on many other non-esoteric topics apart from the Stages of the Path, including the Bodhisattvacaryavatara [4.18-20] and the Seven-Point Mind Training (blo sbyong don bdun), of which he released a well-known edition [5.9].

The Compilation and Publication of Phabongkha’s

Collected Works

The compilation of Phabongkha’s Collected Works took a number of years and was spearheaded by Trijang Rinpoche together with Denma Lobsang Dorje, who was not only the author of Phabongkha’s biography, but also his close student and secretary.[31] Both of these figures also disseminated the oral transmission lineage of the Collected Works.

After Phabongkha’s death a search began to collect scattered notes based on Phabongkha’s oral teachings, and any works penned by him. Various texts were found, although not all of them could be trusted and thus Denma Lobsang Dorje went through all the texts to check their condition.[32] Any notes and other writings that were found or believed by the team to be inaccurate were then corrected. Although the texts are included in Phabongkha’s Collected Works, it was not unusual for the notes of students to form the basis for the creation of works which were then attributed to the teacher, as was the case with Liberation In Your Hand.

The creation of the Collected Works was also a costly affair, as is evident from Trijang Rinpoche’s introduction to the set, which mentions donations given during the carving of woodblocks for volumes one to eight (ka-nya), the first to be created.[33] Phabongkha’s influence and popularity was largely focussed on Lhasa and pockets of Kham and thus sponsors, who included incarnate lamas, geshes and other important religious figures, aristocrats and other officials, tended to be mainly from these regions. Sponsors from Eastern Tibet hailed from areas such as Dragyab (brag g.yab), Lithang (li thang) and Barkham (bar khams). A number of sponsors also came from different parts of both Ü (dbus) and Tsang (gtsang). The introduction lists with transparency how much each sponsor donated, listing the most illustrious donor first- the Fourteenth Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso’s (ta la’i bla ma bstan ‘dzin rgya mtsho,1935-) senior tutor Ling Rinpoche Thubten Lungtok Namgyal Trinle (gling rin po che thub bstan lung rtogs rnam rgyal ‘phril las, 1903-1983), who offered 1000 silver coins (dngul srang). Trijang Rinpoche includes himself at the end of the list, and donated 4000 silver coins. He also makes a special mention of the aristocrats Lhalu Tsewang Dorje (lha klu tshe dbang rdo rje, 1914- 2011) and Lhalu Lhacham Yangdzom Tsering (lha klu lha lcam g.yang ‘dzoms tshe ring, d.u.), who were devoted students of Phabongkha and not only offered 2321 silver coins but also other necessities required for the creation of the new printing blocks as well as earlier work on the collection which took place at Tashi Choeling Hermitage (bkra shis chos gling ri khrod). These two central patrons also receive a special dedicatory mention by Trijang Rinpoche, who, amongst many other aspirations, hopes that through the merit the sponsors accumulate through their offerings, they will always be cared for by Guru Vajradhara (i.e. Phabongkha), and that they may never be parted from Tsongkhapa’s “stainless teachings”.[34]

The carving of the wood blocks for volumes one to eight had begun by 1948 and appears to have carried on through until 1951 and beyond.[35] This means that the collection and checking of texts, which began after Phabongkha’s death in 1941, would have taken more than eight years to complete considering that the remaining volumes following the eighth volume, also had to be prepared.

According to a student of Phabongkha, the original Collected Works was composed of more than the eleven volumes which are currently widely available.[36] Woodblocks for a twelfth volume (na) were carved and texts printed from these. A thirteenth and fourteenth volume was also planned, although these were never published. The twelfth volume, however, appears to not have been included into the publicly distributed editions of the Collected Works due to the inauspicious connotations related to the term “na”, which in Tibetan is a homonym for the word “illness”.[37] This discarded volume and its blocks, along with any of the material intended for the two additional volumes were thought to have been lost during the Cultural Revolution, although it now appears that a copy of the twelfth volume, or rather, what had originally been planned to be released as a twelfth volume, did survive in the Potala Palace’s collection.[38] Although currently I have been unable to definitely ascertain what works were intended for the never-published thirteenth and fourteenth volumes, it may be that the other of the two works by Phabongkha on which Trijang Rinpoche’s Cittamani Tara approximation retreat manual was based (one being Garland of Cittamani) was amongst these texts.[39]

The twelfth volume’s contents are also significant due to the fact that out of eight texts, four are on Vajrabhairava. These include a text for the Vajrabhairava approximation retreat’s preliminary ritual [12.6], a burning offering ritual [12.5] as well as a related explanatory work [12.7], and a self-entry ritual [12.8]. Added to the Vajrabhairava works in the other volumes, these come together to create a comprehensive set of practice texts related to this deity, showing how Phabongkha placed a significant emphasis on this particular practice, which had also been emphasised by Tsongkhapa.

Following the upheavals of the late 1950s and 1960s, the eleven volume Lhasa edition-Collected Works was eventually republished under the title of Collected Works of Pha-bong-kha-pa Byams-pa-bstan- ‘dzin-‘phrin-las rgya-mtsho, between 1973 and 1974 in New Delhi by Chophel Legdan under the guidance of Trijang Rinpoche.[40] This reproduction was based on surviving copies of the various xylographs printed from the Lhasa woodblocks. Several texts, which had origi- nally been included in the tenth volume, tha, but which had been omitted from the republished Delhi edition, were later collected, along with other texts, into an additional volume: A Supplement to the Collected Works of the Lord of Refuge, Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo (skyabs rje pha bong kha pa bde chen snying po’i gsung ‘bum kha skong), published in 1977 by Ngawang Sopa in New Delhi.[41] The contents of the 1977 supplementary volume are as follows:

1. A Collection of The Lord of Refuge, Kyabdag Dorjechang Phabongkha’s Minor Compositions and Instructions

khyab bdag rdo rje ‘chang pha bong kha pa’i bka’ rtsom dang phyag bzhes phran tshegs skor phyogs su bkod pa/

2. Bestowing the Supreme All-Illuminating Wisdom: The Recitation Rituals of the Sadhana of Venerable White Manjusri Set Together Side by Side

rje btsun ‘jam dbyangs dkar po’i sgrub thabs kyi ‘don chog zur du bkod pa kun gsal shes rab mchog sbyin/

3. Extensively Elucidated Outlines of the Essential Instructions of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment Together with Notes which Easily Point Out the Pith Instructions of the Essential Points

byang chub lam gyi rim pa’i dmar khrid kyi sa bcad rgyas par bkral ba/ nyer mkho’i man ngag ‘tshol bde’i mchan dang bcas pa/

4. An Ornament Embellishing Arising Wisdom: An Explanation of the Make-up of the Vairocana-Abhisambodhi [42]

rnam snang mngon byang gi thig ‘grel sher ‘byung dgongs rgyan

5. The Way to Perform the Long-Life Accomplishment Ritual Related to Sita-Tara Cintacakra

sgrol dkar yid bzhin ‘khor lo’i sgo nas tshe sgrub bya tshul/

6. The Essence of the Nectar of Holy Dharma: The Way to Practice the Profound Instructions of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment, Explained in Verse

byang chub lam gyi rim pa’i gdams pa zab mo rnams tshigs su bcad pa’i sgo nas nyams su len tshul dam chos bdud rtsi’i snying po/

7. Newly Arranged Diagrams for the Stages of samatha as Taught in Lord Maitreya’s Mahayanasūtralamkara

byams mgon gyis mdo sde rgyan las gsungs pa’i zhi gnas kyi dmigs rim rnams re’u mig tu gsar bskrun/

8. The Calling the Guru from Afar [Practice Entitled] “The Inseparable Three Bodies”: A Song of Longing Swiftly Drawing the Blessings of the Guru

bla ma rgyang ‘bod sku gsum dbyer med bla ma’i byin rlabs myur ‘dren gdung dbyangs/

The three texts that were already included in the tenth volume (tha) of the original Lhasa edition of the Collected Works but were not included in the 1973-1974 New Delhi edition of the eleven volume set were the collection of minor writings, the Vairocana text (An Ornament Embellishing Arising Wisdom), and the Sita-Tara ritual. This is clear as the folios of each of these works, which were collected by Trijang Rinpoche from surviving manuscripts of the original Lhasa edition, are marked by the letter tha.[43]

Furthermore, two of the works from this supplement, namely the first work, A Collection of The Lord of Refuge, Kyabdag Dorjechang Phabongkha’s Minor Compositions and Instructions [10.3, 12.2] and An Ornament Embellishing Arising Wisdom [10.4, 12.3], are both listed in the Potala’s catalogue as being part of the twelfth “na” volume of the Potala’s edition. These two texts then, can today be found in three separate volumes: the Delhi supplement, the tenth volume of the widely known Lhasa edition, and the twelfth volume of the rare edi- tion in the Potala’s collection. The Sita-Tara text [10.8], however, is only found in the Delhi supplement and in the tenth volume of the Lhasa edition.

The fact that the Minor Compositions and An Ornament Embellishing Arising Wisdom are found in the widely known eleven-volume Lhasa edition, gives credence to the fact that the twelfth volume, as held today in the Potala, was never released to a wider audience. For whatever reason, both works were instead selected to be moved from the planned twelfth volume into the tenth volume of the official Lhasa edition, because, as mentioned above, publishing and distributing a “na” volume would have been inauspicious in this case. As a result, two texts which were already positioned as the third and fourth works of the tenth volume, The Mirror of the View (lta ba’i me long), a commentary to a Kadampa (bka’ gdams pa) transference of consciousness practice, and a text entitled Abbreviated Rites to Protect Harvests from Rain, Frost, Hail, Disease, Drought and So Forth (lo tog gi rim ‘gro dang/ char ‘bebs/ sad ser btsa’ than sogs srung thabs mdor bsdus la/) were removed from the volume, replaced by Minor Compositions and An Ornament Embellishing Arising Wisdom, and are thus today no longer included in the widely available Lhasa edition. A comparison with the Potala catalogue likewise reveals that a Vajrayogini gaṇacakra ritual text was removed to make place for the Sita-Tara Cintacakra longevity practice [10.8], although the work did not come from the twelfth volume. The tenth (tha) volume in the eleven-part Lhasa set contains no contents pages, the only multi-work volume without one, which also points towards a reconfiguration of the volume’s original contents.[44] We know that the volumes were carved and printed gradually and thus volumes one to nine were probably already printed and set at the time that the Minor Compositions and An Ornament Embellishing Arising Wisdom were transferred into the tenth volume. The tenth was probably deemed as a more suitable location for these texts than the eleventh volume, which was reserved exclusively for Liberation in Your Hand.[45]

The remaining texts in the supplementary Delhi volume were most likely drawn from material which would have been included in the thirteenth or fourteenth volumes, should they ever have been published, and thus the folios do not contain any Tibetan letters marking them as belonging to any specific volume.

Some texts that are in wide circulation and use today may also well have been planned to be included in the never-released thirteenth and fourteenth volumes, but were omitted from both the Lhasa and Delhi eleven-volume editions as well as the Delhi supplement. For example, Phabongkha’s re-composition of the common sixty-four part torma offering to the protector Kalarūpa, The Accomplishment of the Four Activities: A Recitation Arrangement of the Sixty-Four Part [Torma Offering Ritual] Organised for Easy and Convenient Recitation (drug cu ma’i ‘don bsgrigs ‘khyer bde nag ‘gros su bkod pa las bzhi’i ‘phril las myur ‘grub), which is widely used and found in numerous Gelug prayer books, appears to be excluded from both the Delhi and Lhasa editions of the Collected Works and is not listed amongst the twelve volumes available in the Potala’s collection.[46] Also excluded from the Collected Works are polemical notes compiled by Denma Lobsang Dorje based on teachings given by Phabongkha in Chamdo, discussing the views of other Tibetan Buddhist schools, as well as Bon.[47]

Another text that does not appear to have been included in the original Lhasa edition of the Collected Works, its later reproductions and reprints, the Delhi supplement, or the Potala edition, is a new initiation ritual manual composed by Phabongkha for the Thirteen Pure Visions of Tagphu (stag phu’i dag snang bcu gsum), also known as the Thirteen Secret Dharmas (gsang chos bcu gsum) or Thirteen Secret Visions (dag snang gsang ba bcu gsum). These “Thirteen Secret Dharmas” refer to a cycle of visionary teachings originating from Tagphu Tulku Lobsang Chokyi Wangchuk (stag phu sprul sku blo bzang chos kyi dbang phyug, 1765-c.1792) and transmitted through his incarnation lineage, down to Tagphu Pemavajra and from him to Phabongkha. The cycle contains practices of deities such as Amitayus, Vajravarahi, Hayagriva, Avalokitesvara and, most importantly, Cittamani Tara. The new initiation manual, entitled The Power to Magnificently Fully Gather The Fruit of the Two Aims: The Rain- fall-Array of Ripening Initiation Rituals of The Thirteen Sealed Secret Dharmas of the Glorious Tagphu, however, appears to have been included in the collected works of Tagphu Pemavajra instead, most likely because the work is directly related to Phabongkha’s teacher’s visionary lineage.[48] It is recorded in Phabongkha’s biography that in the Fire-Horse Year (1906) he requested permission from Tagphu Pemavajra to compose a new initiation manual on the Thirteen Secret Dharmas, the permission-initiations of which he then subsequently bestowed upon a gathering of fifteen high-ranking incarnate lamas over a period of about a week.[49] The woodblocks for the text were apparently only carved in 1935.[50]

The Guru-Deity-Protector Triad

The life-entrustment ritual of Dorje Shugden, The Chariot of the Jewel of Faith Drawing Together a Precious Mass of Blessings [7.11], composed by Phabongkha dates from 1935, when he was visiting Tagphu Dorjechang at the latter’s monastery of Tagphu Drubde Geden Lugzang Kunphelling (stag phu sgrub sde dge ldan lugs bzang kun ‘phel gling) in Nagshoe (nags shod), Kham. The colophon to the text states that it was both Phabongkha, as well as his visionary teacher, who together brought the “profound words” of the ritual to maturation.[51] Phabongkha’s close affinity to Shugden, however, does not appear to have been confined to the final years of his life. In the colophon to The Melodious Drum Victorious in All Directions [7.14], Phabongkha’s seminal fulfillment ritual of Dorje Shugden, he describes how he had been lovingly cared for by Shugden, who was compassionately at- tached to him like “the body is to a shadow”, since his youth (“lus dang grib ma bzhin du brtse bas bskyangs bskul”).[52] The composition of the text in question, whose block prints for the Collected Works are dated 1948, thus amongst the first to be carved, was begun in the Wood-Ox Year of 1925 when Phabongkha was in his late 40s, but the complete text with its colophon and its verses of auspiciousness appears to have only been finalized by Phabongkha in 1929.[53]

Shugden, as is obvious from the epithets that Phabongkha used in relation to the deity: “Protector of Lord Manjusri [Tsongkhapa]’s Teachings (‘jam mgon bstan srung)” and “Protector of the Virtuous [Gelug] Teachings (dge ldan bstan srung)”, was indeed considered by Phabongkha as an important protector of the Gelug tradition.[54] Without Phabongkha’s efforts and writings based on the revelation of the cycle by Tagphu Pemavajra, the cult of the deity would most likely not have become as widespread as it is today. Yet, based on what we can deduce from his Collected Works, did Phabongkha lead a “charismatic movement”, or similar, centred on Shugden, Vajrayogini and himself as a sacred triad of esoteric Gelug doctrine, as Donald Lopez suggests? Georges Dreyfus agrees and writes, perhaps more strongly, that Phabongkha “created a new understanding of the Ge-luk tradition focused on three elements: Vajrayogini as the main meditational deity (yi dam), Shuk-den as the protector, and Pa-bong-ka as the guru”.[55] Although this is a commonly held view, here I would like to at suggest that Phabongkha created no such understanding.

Despite the epithets that Phabongkha used in relation to Shugden in his works, he was not exclusively focused on Shugden as the only protector worthy of writing on. Most Tibetan Buddhist works bestow superlative epithets to the deities they are focused on and thus these titles alone cannot tell us how important or central a specific deity was. Compiled together with Phabongkha’s Shugden works in the same volume is another set of five texts, these being focused on “The Glorious Four-Faced Protector” (dpal mgon gdong bzhi pa), Caturmukha Mahakala, who in the Gelug tradition is a protector of the Cakrasamvara cycle.[56] These include a long ritual text of permission initiations (rjes gnang) for the different manifestations of the deity, and various other works [7.5-7.9]. It is not surprising, considering Phabongkha’s emphasis on Cakrasamvara, that he would compose a substantial set of texts on this form of Mahakala, which in simple terms of page numbers, is considerably larger than his writings on Shugden. This demonstrates that while Phabongkha himself promoted Shugden as an important protector, the deity nevertheless remained within a wider pantheon of wrathful deities that Phabongkha considered important. Interestingly Phabongkha’s writings on Shugden, based on Tagphu Pemavajra’s pure visions, prescribe a life-entrustment initiation, usually reserved for more lowly worldly protectors (‘jig rten pa’i srung ma), instead of a permission initiation, such as those bestowed for the different manifestations of Caturmukha Mahakala and other deities categorized as enlightened. Clearly Phabongkha did not take that one step further and promote Shugden directly to the level of an enlightened protector, which may well have been too obtrusive a move, but instead kept him ranked at the level of a worldly protector, who nevertheless, in reality, is an emanation of Manjusri simply appearing as a gyalpo, or “king”-spirit (rgyal po), as a manifestation of his enlightened activities.[57] Shugden, as numerous textual sources attest, certainly existed within the Gelug and other lineages, specifically those of the Sakya sect, before Phabongkha and his teachers, and appears to have been consistently classed as a gyalpo.

Shugden’s ranking as a worldly being is clear from a comparison with another popular protector, Pehar (dpe har). Like Shugden, Pehar is classed as a gyalpo being, and both are often referred to with the titles of either “Gyalpo” or “Gyalchen” (rgyal chen), meaning “great king”- although the titles can also be used as an honorific and not necessarily to refer to a class of spirit. The same is true for Pehar’s five manifestations, the Five Gyalchen (rgyal chen sku lnga), who, like Shugden, have an associated life-entrustment ritual instead of a permission initiation.[58] Pehar is a protector of the Tibetan Government hailing from the Nyingma tradition who through his minister, Dorje Drakden (rdo rje grags ldan), makes himself manifest through the Nechung Oracle (gnas chung sku rtan), a human medium who in turn functions as the primary state oracle. Shugden likewise manifests through human mediums, relegating his outward ranking to that of a worldly deity in the eyes of most Tibetan Buddhists, as enlightened protectors are generally understood not to take possession of mediums, an activity reserved for worldly spirits and protectors. Shugden’s actual nature as a manifestation of Manjusri is likewise highly contested by most Tibetan Buddhists, however a number of other protectors, including Pehar, are also the subject of disagreements (as to whether or not they are truly enlightened), although certainly not as heated.[59]

Phabongkha’s promotion of Vajrayogini as a meditational deity is not unique within the Gelug tradition and has an established history within the lineage. Tagphu Lobsang Tenpai Gyaltsen (stag phu blo bzang bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan, 1714-1762), for example, composed a commentary on the two stages (rim gnyis) and Tuken Lobsang Chokyi Nyima wrote a large collection of practice texts and instructions on the deity that rival Phabongkha’s in breadth, and which Phabongkha himself used as a basis for his own compositions, along with the related works of Ngulchu Dharmabhadra (dngul chud+harma b+ha dra, 1772-1851) and others.[60] Art historical evidence also confirms the existence of Vajrayogini in the Gelug tradition in the eighteenth century, as can be seen from a number of thangka (thang kha) paintings and other works produced at the Qing court during the period of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735- 1796), and his guru Changkya Rolpai Dorje (lcang skya ro pa’i rdo rje, 1717-1786), for example, who was also a Vajrayogini practitioner, as well as many other instances.[61] Thus while the Vajrayogini Naro Kechari lineage was passed into the Gelug tradition from the Sakya (sa skya) lineage, and all evidence points to the fact that the practice of the deity and all of these works in the Gelug tradition are certainly post-Tsongkhapa, it is clear that Phabongkha was drawing from an already well-established practice within his own lineage. Despite the unique Vajrayogini lineage stemming from Phabongkha being the most well-known today, it appears that another lineage or lineages of practice stemming from Amdo (a mdo)-based teachers such as Tuken were previously widely practiced, at least in their native regions. Although today these lineages have become rare, they are apparently not extinct.[62]

Phabongkha’s many compositions on Vajrayogini do not mean that he had a calculated plan for the practice to become an institutionalized central facet of the Gelug tradition. It is obvious from the colophons of a number of his compositions on the deity that requests came from many of his close students, including several high-ranking aristocratic women. A number of female practitioners were understandably attracted to this solitary female deity, whose teachings and practice, furthermore, are relatively simple compared to those of the three main Gelug meditational deities, including Cakrasamvara, and in particular the sixty-two deity body mandala (lus dkyil) form emphasized by Phabongkha. Women, lay or ordained, did not have access to religious education as monks or even lay men did, and thus Vajrayogini presented them with a simple and efficacious alternative. Even today all of the Gelug nunneries in Lhasa, as well as many in India and Nepal, continue to practice Phabongkha’s Vajrayogini gaṇacakra and/or self-entry rituals communally in their assembly halls on a monthly basis, whereas this is unheard of in male Gelug monastic institutions. This analysis, however, does not exclude men, who would also of course have benefited from such a concise yet profound practice, making the attraction of the deity to a large following of adherents easy to understand. Phabongkha clearly had a connection on a spiritual level with the deity (as he did with Shug- den) and the reasons for his composition of works on Vajrayogini’s practice may not have been any more unusual than those of previous Gelug teachers who taught and wrote on the deity, and indeed on any deity- being that they were requested by students and saw a need for new texts. In fact some of these reasons are included within the colophons or introductions to his texts.[63] Texts that were written by a teacher out of his own accord or for his own personal practice are often noted as such in the colophon. However it was common for Tibetans to request their own teachers to re-write existing sadhanas, usually resulting in minor differences.[64] Phabongkha’s Vajrayogini sadhana, The Swift Path to Great Bliss (bde chen nye lam), was based on existing Gelug examples, most obviously Tuken’s sadhana, which has the same title, and follows the same schemata and essential visualizations, however Phabongkha clearly expanded on the work.[65]

In relation to Phabongkha’s promotion of Vajrayogini, Dreyfus writes that “The novelty of his approach is even clearer when we consider Pa-bong-ka’s emphasis on Tara Cintamaṇi [sic] as a secondary meditational deity, for this practice is not canonical in the strict sense of the term but comes from the pure visions of one of Pa-bong-ka’s main teachers, Ta-bu Pe-ma Baz-ra (sta bu padma badzra) [sic]”.[66] Dreyfus goes on to say that although Phabongkha did not introduce these deities into the tradition himself, but rather received them from his teachers, it is his unprecedented promotion of these “secondary practices” by making them “widespread and central to the Ge-luk tradition and claiming that they represented the essence of Dzong-ka- ba’s [Tsongkhapa’s] teaching” which made him innovative.[67] This statement is only partly true. For example, Phabongkha appears to have only composed one or two texts on Cittamani Tara, i.e. the commentary on the generation and completion stages mentioned earlier, which does not suggest an emphasis on the practice.[68] Vajrayogini, as has already been noted, was already a very popular deity amongst a number of highly influential eighteenth century scholars such as Tuken, who wrote on the practice extensively. More importantly it is clear from the works of these scholars that Vajrayogini was already considered by a number of leading teachers as the “uncommon secret dharma hidden in the mind” of Tsongkhapa, i.e. his secret meditational deity.[69] If this belief was already extant in the eighteenth century amongst high-ranking religious figures, then it is certainly understandable as to why Vajrayogini was considered so important and why Phabongkha would follow the same tradition and its interpretations. In this sense, Phabongkha was far from innovative.

Dreyfus also repeats, specifically in relation to Shugden, that Phabongkha “transformed a marginal practice into a central element of the Ge-luk tradition. This transformation is illustrated by the epithets used to refer to Shuk-den”.[70] Although these epithets have already been mentioned above, here it is also necessary to point out that epi- thets like “Protector of Lord Manjusri [Tsongkhapa]’s Teachings”, like the view of Vajrayogini as Tsongkhapa’s secret meditational deity, far predate Phabongkha, and thus do not in themselves prove his elevation of Shugden into a “central element”. In fact one of the exact same epithets used by Phabongkha, i.e. “Protector of Lord Manjusri [Tsongkhapa]’s Teachings” can be found in the title of a text by the seventeenth to eighteenth century teacher Dragyab Lobsang Norbu Sherab (brag g.yab blo bzang nor bu shes rab, d.u.), entitled The Way to Perform the Invocation of Gyalchen Dorje Shugden Tsal, Protector of Lord Manjusri [Tsongkhapa]’s Teachings, one of the earliest instances of the usage of the title.[71] A number of other later usages of this or similar titles pre-dating Phabongkha do exist, suggesting that Phabongkha was following the example of select previous Gelug teachers in his propitiation of Shugden. It is almost impossible to estimate the popularity of Shugden in the various regions of Tibet and Mongolia before the twentieth century. The major difference with these earlier teachers and Phabongkha, however, was the latter’s popularity, which resulted in a wider dissemination of anything he taught, often to an audience of politically and religiously influential figures. This, as with the case of Vajrayogini, however, should not necessarily be taken to mean that he purposefully conceived of disseminating the practice of the protector more than his predecessors.