The Mystical Land of Shambhala

(By Tsem Rinpoche)

For thousands of years, stories have been told of a mystical paradise called Shambhala. Hidden within the Himalayan Mountains, it has come to be known by many other names: Shangri-La, the Land of White Waters, the Forbidden Land, the Land of the Living Gods, the Land of Radiant Spirits, and the Land of Living Fire. The Chinese call it Hsi Tien. The Hindus call it The Land of the Worthy Ones or Aryavartha. The Russians refer to it as Belovoyde, and to the Bön, it is called Tagzig Olmo Lung Ring.

Shambhala has sparked the imagination and curiosity of many generations, faiths, cultures, and nationalities, and those with adventurous natures have even attempted to search for the physical location of this paradise, which is said to be filled with wish-fulfilling trees and clear jewel-like lakes.

In the English translation of “The Journey to Śambhala” (Sambalai Lam Yig) provided below, His Holiness the 6th Panchen Lama describes in great detail how to enter this mystical land. This text was translated into German from the original Tibetan, and I had it translated into English. It was expensive and took many months of translating, editing and checking, but I decided to proceed with this endeavour for the benefit of you, the readers.

The purpose of this article is to explain about the realm of Shambhala from both Buddhist and Western perspectives, to introduce the Kalachakra Tantra which is linked to Shambhala and the Panchen Lama’s incarnation lineage. This article also provides information on His Holiness the 6th Panchen Lama and his official seat, Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. May this article be of benefit to those who wish to learn more about this land of spiritual evolution, peace and happiness.

Tsem Rinpoche

The Legend of a Mystical Paradise Called Shambhala

The name Shambhala in Sanskrit means ‘a place of peace/tranquility/happiness’ or ‘place of silence’. It is considered a pure land within the Human Realm. Pure lands are places where one’s physical needs are easy and worry free, and because of that one can concentrate on spiritual practice to achieve higher states of consciousness. In essence, pure lands provide practitioners with the most effective circumstances to progress on their spiritual path. Whereas most pure lands exist in higher realms of existence such as the God Realm, Shambhala is unique. It exists in our very own Human Realm. The existence of this specific mystical paradise is mentioned extensively in the Kalachakra Tantra.

There are many places within our Human Realm, where according to Tantric scriptures, energies from different dimensions or levels of consciousness converge. These are extremely sacred and mystical sites, and our experiences when, we visit these sites, vary according to our spiritual maturity. For example, the Heruka Chakrasamvara Tantras speak of 24 such locations in India and in each of these locations the entire mandala of Heruka Chakrasamvara is present. Those who practice Tantra in these locations are said to excel in their practice due to the enlightened energies there, which facilitate internal energetic processes better than in other physical locations. Shambhala is another location where there are perfect conditions for us to practice, especially the Tantric practice of Kalachakra. But unlike the 24 sacred sites associated with Heruka Chakrasamvara in India, Shambhala exists as its own kingdom separated from the worldly affairs of other countries and kingdoms.

According to the Kalachakra Tantra scriptures, the first king of Shambhala, King Suchandra, requested Buddha Shakyamuni to bestow upon him a practice that would not require the renunciation of his secular responsibilities to govern over his kingdom and people. Upon receiving this request, Lord Buddha bestowed the complete initiation into the Kalachakra practice to the king, and also expounded the Kalachakra Root Tantra to the monarch and his entourage of 96 minor kings and officials at the site of Dhanyakataka, located in the present-day Andhra Pradesh in south-eastern India.

In the Paramadibuddha, the Kalachakra Root Tantra, it is said:

“Then Vajrapani’s emanation, King Suchandra from famous Shambhala, miraculously entered into the splendid sphere of phenomena. First, he circumambulated to the right, then he worshipped the teacher’s lotus feet with flowers made of jewels. Placing his hands together, Suchandra sat before the perfect Buddha. Suchandra requested the Buddha for the tantra, redacted it, and taught it too.”

Source: dalailama.com

It is said that at the time Buddha Shakyamuni bestowed the Kalachakra practice, he held another teaching session simultaneously on the Prajnaparamita Sutra at Griddhraj Parvat (Vulture’s Peak), in what is the present-day Bihar.

The king and his entourage returned to Shambhala, and King Suchandra practised the Kalachakra Tantra diligently and gained many spiritual attainments. Then, he spread the Kalachakra teachings amongst his subjects and to the next king. Since then, all the subsequent kings of Shambhala became the lineage holders of the Kalachakra Tantra, and Shambhala produced many powerful Kalachakra practitioners. Two of the Shambhala’s kings, Manjushri Yashas and Pundarika, composed a condensed form of the Kalachakra Tantra called the “Shri Kalachakra Laghutantra”, and its commentary, the “Vimalaprabha”, that have become the heart of contemporary Kalachakra practice today.

The existence of Shambhala is also mentioned in the old scriptures from Zhang Zhung, an ancient pre-Buddhist kingdom in western or north-western Tibet. The Vishnu Purana, a Hindu scripture, also refers to Shambhala as the future birthplace of the final incarnation of the god, Vishnu, who will welcome a new Golden Age to the world.

According to the legend, Shambhala is a place where wisdom and love reign, and there is no crime. The kingdom of Shambhala is said to be in the form of an eight-petaled lotus, and the king of Shambhala rules from the city of Kalapa at the centre of this lotus. The residents of Shambhala have pure hearts, and they are immune to suffering, aging, and want. They are healthy and live for hundreds of years, and the food that they need for sustenance grows easily. The people of Shambhala consist of several well-defined classes: the farmers, the scholars, and the nobles, who all live harmoniously together.

In our world, the Panchen Lama’s line of incarnations are considered to be the emanations of one of the kings of Shambhala, King Manjushri Yashas, and are some of the greatest holders of the Kalachakra Tantra. Until today, there is a custom in Tibet for the Panchen Lama to give public Kalachakra initiations. Though Tantra is usually practised in private, the Panchen Lama incarnations bestow the initiation to huge crowds, and it is considered a very rare and special blessing to receive the initiation from the Panchen Lama. The Kalachakra Tantra is also practised strongly at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, the official seat of the Panchen Lama in Shigatse, Tibet.

His Holiness the 11th Panchen Lama Gives Kalachakra Initiation

Or view the video on the server at:

https://video.tsemtulku.com/videos/PanchenLamaKalachakra.mp4

The Location of Shambhala

Altai folklore has it that the gateway to Shambhala is located on Mount Belukha

There are many legends associated with the location of Shambhala. The Zhang Zhung scriptures mention that Shambhala is located in the Sutlej Valley in Punjab, while the Mongolians believe that it is located in a valley in Southern Siberia. Altai folklore has it that the gateway to Shambhala is located on Mount Belukha, and modern Buddhist scholars believe that Shambhala is located in the high reaches of the Dhauladrar Mountain Range in the Himalayas.

The geographical teachings in the Kalachakra Tantra indicate that Shambhala is located to the north of India, and according to the measurements provided by these teachings, this pure land is located in a sacred place for Buddhists, Hindus, Bön and Jains, Mount Kailash.

Mount Kailash

The Kalachakra teachings also give a vivid description of Shambhala, and it is said to be located in a valley surrounded by mountains. Within this valley, there are two lakes that are conjoined by land, upon which the 1st Shambhala king built his palace.

In his book titled “Shambhala: In Search of the New Era”, Nicholas Roerich wrote:

“Great Shambhala is far beyond the ocean. It is the mighty heavenly domain. … Only in some places, in the Far North, can you discern the resplendent rays of Shambhala.”

Source: Roerich, Nicholas, “Shambhala: In Search of the New Era”, Vermont, Inner Traditions, 1990, p. 2

His Holiness the 3rd Panchen Lama Ensapa Lobsang Dondrup stated that the kingdom of Shambhala is actually three different things:

- A symbol representing the attainment of the Kalachakra practice

- An enlightened pure land

- An actual physical location

Whichever it may be, the kingdom has a special place in the hearts of devotees as each of these is important for practitioners of the spiritual path. This is one of the reasons why the myths, legends and stories about Shambhala are so varied. Some are meant to be taken literally while others are metaphors for one’s spiritual journey to a higher state of consciousness.

It is also stated that even though you may have reached the physical location of Shambhala, you may not necessarily realise you are there, because of your karma. For example, on the physical level you may see a river of water, but the same river will be seen by hungry ghosts as pus; aquatic animals will see it as their home; and the gods and those with higher spiritual attainments will see the river as divine nectar. In the same manner, though you may have reached the physical site of Shambhala on the earthly plane, you may not be able to recognise it on the spiritual plane as you may not have the karma to see and experience it. This theory accords with the fact that Shambhala can be viewed as a convergence of different dimensions or realms.

The Kings of Shambhala

There are 32 known kings of Shambhala (past, present, and future), comprising seven Dharmarajas and 25 Kalki Kings. The first known ruler was Suchandra, who received the Kalachakra Tantra teaching directly from Buddha Shakyamuni, and spread the Tantric practice to the next king and to the citizens of Shambhala.

There were two other notable kings, Manjushri Yashas and Pundarika. Manjushri Yashas wrote a condensed form of the Kalachakra Tantra titled “Shri Kalachakra Laghutantra”. He was also known for converting a group of non-Buddhist priests in Shambhala and initiating them into Kalachakra practice. Manjushri Yashas also predicted the arrival of “Barbarian Dharma” 800 years later (about 600 CE). The prophecy came true with the arrival of non-Buddhist invaders in South Asia around 636-643 CE. In his introduction to the German version of “The Journey to Śambhala” which was written by the 6th Panchen Lama Lobsang Palden Yeshe, Albert Grunwedel, a German Tibetologist, wrote that:

“…the Panchen had a duty to gather together the material about a wonderland, in which he himself should have been the king in his previous existences, because he was once the celebrated [Manjushri] Yasas or Manjughosa(kirti)”

Source: Grunwedel, Albert, “The Journey to Śambhala”, Munich, Bavarian Academy of Sciences, 2010, p. 4

Manjushri Yashas is said to have abdicated and passed the throne to his son, Pundarika. Not long after his abdication, Manjushri Yashas entered clear light and achieved the state of Buddhahood. Pundarika was known for writing the commentary to the Shri Kalachakra titled the “Vimalaprabha” (Stainless Light). Both the Shri Kalachakra and Vimalapraba are the source texts for Kalachakra Tantra that are still in use today.

The complete list of Shambhala kings are as follows:

The Seven Dhamarajas

- Suchandra – a manifestation of Vajrapani

- Devendra, Fond of Sentient Beings – a manifestation of Ksitigarbha

- Tejasvin, Bearer of the Dharma Wheel and the Auspicious Conch – a manifestation of Yamantaka

- Somadatta, Lord of Speakers – a manifestation of Sarvanivarnaviskambhin

- Deveśvara/Sureśvara, Destroyer of the City of Delusion – a manifestation of Jambhaka

- Viśvamūrti, Conqueror of False Leaders, Holding a Lotus – a manifestation of Manaka

- Sureśana, Cutter of Delusion, Uprooter of Karma and Klesha – a manifestation of Khagarbha

The Twenty-Five Kalki Kings

- Manjushri Yashas – a manifestation of Manjushri

- Pundarika, White Lotus, Cherished by the Lord of Potala – a manifestation of Avalokiteshvara

- Bhadra, One Who Rules by the Thousand-spoked Wheel – a manifestation of Yamantaka

- Vijaya, Attractor of Wealth, Victorious in War – a manifestation Kshitigarbha

- Sumitra, Integrator of Method and Wisdom, Victorious over Samsara – a manifestation of Jambhaka

- Raktapani, Holder of the Blissful Vajra and Bell – a manifestation of Sarvanivarnaviskambhin

- Vishnugupta, Smiling Holder of the Trident and Rosary – a manifestation of Manaka

- Suryakirti, Annihilator of Wild Demons – a manifestation of Khagarbha

- Subhadra, Holder of the Sword and Shield – a manifestation of Vighnantaka

- Samudra Vijaya, Annihilator of All Types of Devils – a manifestation of Vajrapani

- Aja, Who Binds with Unbreakable Iron Chains – a manifestation of Yamantaka

- Surya/Suryapada, All-Pervading, Radiant Jewel Light – a manifestation Kshitigarbha

- Vishvarupa, Holder of the Vajra Prod and Noose – a manifestation of Jambhaka

- Shashiprabha, Lord of Secret Mantras, Holder of the Wheel and Conch – a manifestation of Sarvanivarnaviskambhin

- Ananta/Thayä, Holder of the Mallet that Crushes False Ideas – a manifestation of Manaka

- Shripaala/Parthiva, Holder of the Cleaver that Cuts the Bonds of Ignorance – a manifestation of Khagarbha

- Shripala, Annihilator of the Host of Demons – a manifestation of Vighnantaka

- Singha, Who Stuns the Elephant with His Vajra – a manifestation of Vajrapani

- Vikranta, Subduer of the Mass of Foes, the Inner and Outer Classes of Devils – a manifestation of Yamantaka

- Mahabala, Tamer of All False Leaders by Means of the Sound of Mantra – a manifestation of Kshitigarbha

- Aniruddha (the current king), Who Draws and Binds the Entire Three Worlds – a manifestation of Jambhaka

- Narasingha, Ruling by the Wheel, Holding the Conch – a manifestation of Sarvanivarnaviskambhin

- Maheshvara, Victorious over the Armies of Demons – a manifestation of Khagarbha

- Anantavijaya, Holder of the Vajra and Bell – a manifestation of Vajrapani

- Raudra Chakrin, Forceful Wheel Holder – a manifestation of Manjushri

Raudra Chakrin is believed to be the future and final king of Shambhala. According to a prediction within the Kalachakra Tantra, Raudra Chakrin will defeat the degenerated rulers of the future and usher in the last Golden Age. Following that Golden Age, the Dharma will degenerate and completely disappear from the world. After hundreds of thousands of years without the Dharma, the next Buddha of our time, Maitreya, will take birth once again to turn the wheel of Dharma.

The Prophecy of Shambhala

The Kalachakra Tantra predicts that the world we live in will degenerate into war and greed as materialism and self-indulgence spreads, and those who follow the ideology of materialism will be known as barbarians (mleccha). In the future, when the barbarians and the evil kings who rule them, believe that there is nothing else for them to conquer, the mist that keeps Shambhala hidden will disappear, and the physical location of this paradise will become known to the barbarians.

The barbarians and their kings will attempt to invade Shambhala with their huge armies and their dreadful and powerful weapons. In response to this attack, the 25th Kalki King of Shambhala, Raudra Chakrin, will lead a vast army to eliminate the dark forces and usher in a Golden Age to our world.

According to Alexander Berzin, this event will occur in 2424 CE. However, some theologians interpret this war to only be a symbolic one, because the Buddha’s teachings do not support violence. The battle represents the inner conflict as the practitioner fights against their negative tendencies, such as greed, anger, and selfishness. This is consistent with the explanation given by Khedrub Je, one of Lama Tsongkhapa’s students:

“[The] ‘holy war’ symbolically, teaching that it mainly refers to the inner battle of the religious practitioner against barbarian tendencies.”

Source: en.wikipedia.org

The force of karma is what controls sentient beings who are driven by selfish instincts, customs, and habits created by not understanding the nature of reality. Therefore, these beings hurt and fight each other and create karma. This karma develops into habits and tendencies to continue the cycle, which creates new forces of karma.

It is because of this, the battle described in the Kalachakra prophecy is an inner one, and the invaders are the winds of delusions and afflictive emotions caused by karma running wild within our body. Practitioners of Tantra bring these psychic winds together and dissolve them in the heart chakra. When practitioners succeed in achieving this, they will then see the subtlest level of the mind, the clear light mind. This clear light mind is the deepest and most ultimate meaning of Inner Shambhala, the land of peace.

Therefore, from this prophecy, it can be said that in the future, King Raudra Chakrin will lead sentient beings in a fight against their negative tendencies which create so much suffering, and usher in a Golden Age rather than doing battle against an actual outer enemy.

How to Travel to Shambhala

Although Shambhala exists within the Human Realm, it lies within a different dimension that we usually cannot interact with. It is said that only those who have the merits and affinity will be able to visit this pure realm. The 14th Dalai Lama mentioned that:

“Although those with special affiliation may actually be able to go there through their karmic connection, nevertheless it is not a physical place that we can actually find. We can only say that it is a pure land, a pure land in the human realm. And unless one has the merit and the actual karmic association, one cannot actually arrive there.”

Source: ancient-origins.net

Those who wish to travel to Shambhala can reach their destination by three methods:

- By birth

- By physically finding the place

- By astral travel

There are many accounts of yogis who, being advanced in their meditation, have visited Shambhala by astral travel, and have described the size, location, and appearance of the place, along with instructions on how to reach it. Other practitioners have also travelled physically to Shambhala.

In his book, “Shambhala: In search of the New Era”, Nicholas Roerich wrote:

“We know which Tashi Lama (Panchen Lama) visited Shambhala. … We know how some high lamas went to Shambhala, how along their way they saw the customary physical things. We know the stories of the Buryat lama, of how he was accompanied through a very narrow secret passage. We know how another visitor saw a caravan of hill-people with salt from the lakes, on the very borders of Shambhala.”

Source: Roerich, Nicholas, “Shambhala: In Search of the New Era”, Vermont, Inner Traditions, 1990, p. 2

The Line of Panchen Lamas

The Panchen Lama’s line of incarnations are believed to be the emanations of the Buddha Amitabha and at the same time they are considered to be emanations of King Manjushri Yashas. The Panchen Lamas are also considered to be one of the most important tulkus (reincarnated masters) within the Gelug lineage. The word “Panchen” is an abbreviation of the Sanskrit word “Pandita”, which means “Scholar”, and “Chenpo”, a Tibetan word which means “Great”. Therefore, “Panchen Lama” means “Great Scholar-Teacher”.

The first Panchen Lama to receive this title was Lobsang Chokyi Gyaltsen, the teacher of His Holiness the 5th Dalai Lama. Lobsang Chokyi Gyaltsen is considered to be the 4th Panchen Lama. Khedrup Gelek Pelzang (Khedrup Je), Sonam Choklang, and Ensapa Lobsang Dondrup were posthumously acknowledged as the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Panchen respectively. The 5th Dalai Lama also offered Tashi Lhunpo Monastery in Shigatse (which was built by the 1st Dalai Lama) to the Panchen Lama and his subsequent incarnations. Because the Panchen Lama’s main seat is at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, some westerners, like Nicholas Roerich, refer to him as the Tashi Lama.

Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, Shigatse

When the 4th Panchen Lama entered clear light, the 5th Dalai Lama initiated the search for his reincarnation. He also reserved the title “Panchen” for the subsequent Panchen Lama. In 1713, Emperor Kangxi bestowed the title “Panchen Erdeni” to the 5th Panchen Lama. “Erdeni” in the Manchu language means “treasure”.

The Panchen Lama is a highly realised being, and his incarnations can be traced back to the time of Buddha Shakyamuni. He is said to have many emanations not only on our planet but in various other dimensions and world systems.

The 6th Panchen Lama

His Holiness Lobsang Palden Yeshe (1738 – 1780 CE), the 6th Panchen Lama, was the author of “The Journey to Śambhala”. He was also the brother of an important Kagyu Lama, the 10th Shamarpa, Mipam Chodrup Gyamtso.

Early Life

The 6th Panchen Lama was born in Rangdi Tashi Ze in Southern Tibet to a man named Tangla, and a lady of aristocratic background named Nyida Angmao. After going through strict religious rituals and exhaustive tests, he was identified as the reincarnation of the 5th Panchen Lama. The 7th Dalai Lama sent officials to confirm the boy’s identity and invited him and his guardians to Lhasa. The 7th Dalai Lama then informed the Qing Amban (the grand minister of the Qing Empire in Tibet), Ji Shan about the discovery of the 6th Panchen Lama. Upon receiving the approval from Emperor Qianlong (1711 – 1799 CE), the 7th Dalai Lama bestowed the 6th Panchen Lama his Buddhist name, Lobsang Palden Yeshe.

The enthronement ceremony of the 6th Panchen Lama was held on June 4, 1741 at the Riguang Hall (Sunlight Hall) of Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. The grand event was attended by influential personalities including the emissaries of Emperor Qianlong and the 7th Dalai Lama.

When His Holiness the 7th Dalai Lama entered clear light in 1757, the 6th Panchen Lama instructed the monks at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery to recite Buddhist scriptures for three consecutive days to pay homage to the great spiritual leader. In June of the same year, the 6th Panchen Lama received full monastic ordination from his Sutra teacher, Luosang Qunpei.

One year later, in April 1758, an influential Buddhist teacher from the Qing Court, Changkya Rolpai Dorje, visited the 6th Panchen Lama to discuss the religious and political affairs of Tibet. It seemed that the two influential lamas bonded and forged a great relationship with each other. In February 1759, Changkya Rolpai Dorje invited the 6th Panchen Lama to hold a mass Kalachakra initiation for 6,000 lay people and members of the monastic community. This ceremony coincided with the inauguration ceremony of the 7th Dalai Lama’s reliquary stupa.

The Search for the 8th Dalai Lama

The line of Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas have a very special relationship; when one passes into clear light, the other searches for the correct reincarnation, enthrones them and ensures that they receive the teachings of the lineage. In this way the teachings are preserved and spread for the benefit of countless people. This was evident in the manner that the 7th Dalai Lama found and enthroned the 6th Panchen Lama.

Following this important tradition, in 1760 the 6th Panchen Lama dispatched a group to search for the reincarnation of the 7th Dalai Lama. Later, with Emperor Qianlong’s blessings, he brought the boy who was the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation to Tibet. The 6th Panchen Lama gave the boy his ordination vows, hosted his enthronement ceremony at the Potala Palace, and gave him the name Jamphel Gyatso. The 6th Panchen Lama also acted as a regent to the youthful 8th Dalai Lama.

The 6th Panchen Lama’s management of Tibetan spiritual and political affairs seemed to impress the powerful Emperor Qianlong. In 1766, the Emperor sent his envoy to Tashi Lhunpo Monastery to convey his imperial edict that read:

“The Panchen Lama is a highly accomplished lama of noble character and prestige, who as the guru of the Dalai Lama and is proficient in Dharma, should preach to the clergy and lay people to abide by the commandments strictly, consolidate the Buddhist course of development that safeguards Tibet, and strive to teach virtue and courtesy to every common person in Tibet.”

Source: eng.tibet.cn

With this imperial edict, Emperor Qianlong offered the 6th Panchen a golden seal that weighed 11.5 kg (25.3 lbs) with his title carved on it. The 6th Panchen Lama wrote a memorial to Emperor Qianlong to express his appreciation.

The Progressive Lama

The 6th Panchen Lama was known for his progressive thinking, his writings, and his diplomatic roles and interests. He was also known as a peacemaker, especially in regional conflicts; for playing an important role in maintaining Tibet’s safety; and for his influence in the Qing Court.

In 1774, the British East India Company, which represented the interest of Britain in the Indian Ocean region, was engaged in a military conflict with the Kingdom of Bhutan. The king of Bhutan (Druk Desi) at the time, Kunga Rinchen, requested the 6th Panchen Lama’s help to mediate the conflict and negotiate peace with the British envoys. Druk Desi was the secular leader of Bhutan, while Je Khenpo, the religious leader, held spiritual leadership in Bhutan.

Sensing the opportunity to widen the influence of the British Empire, Warren Hastings, the Governor General of India, sent George Bogle, a Scottish diplomat, to meet the 6th Panchen Lama at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery to establish free trade between China, Tibet, and Britain. The 6th Panchen Lama explained to Bogle in an Indian language that Bhutan was China’s Vassal State, and Tibet was part of China. Therefore, a decision that involved a foreign force such as Britain was the privilege of the Emperor Qianlong.

The 6th Panchen Lama Received George Bogle, an oil painting by Tilly Kettle c. 1775

After this conversation, Bogle was forced to abandon his plan to set up a representative office in Lhasa, and instead set out to meet with a Chinese Amban or high official. Druk Desi then proceeded to sign a peace treaty with Britain, which required Bhutan to return to its pre-1730 boundaries, and allowed the British to harvest timber in Bhutan. The Bhutanese were also requested to offer 5 horses as a symbolic tribute to Britain. Although the negotiation did not end well for Bogle, it is said that he continued to be courteous to the 6th Panchen and their relationship was amicable.

In addition to his powerful connections, the 6th Panchen Lama was known for his literary endeavours. He wrote “The Journey to Śambhala”, which contains detailed descriptions of how to enter the kingdom and lists its geographical attributes.

Relationship with the Qing Court

Xumi Fushou Temple

In 1778, Emperor Qianlong invited the 6th Panchen Lama to his 70th birthday celebration in Beijing. The 6th Panchen Lama accepted the invitation and left with a large entourage in 1780, and Chinese officials greeted him along the way to the capital. To mark the arrival of the 6th Panchen Lama in China, Emperor Qianlong ordered the construction of Xumi Fushou Temple on Chengde Mountain, which was modelled after Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. Throughout his stay in Beijing, the 6th Panchen Lama was showered with riches and honour.

Unfortunately, in that same year, the 6th Panchen Lama entered clear light in Beijing on November 2, 1780.

Prayers

The 6th Panchen Lama was well known for his works related to both Kalachakra practice and also Shambhala. He wrote a handful of prayers which united both concepts of Tantric practice and the mythology of Shambhala together. These prayers are actually intended for daily practice and take the form of Guru Yoga meditations. Each of these prayers begins with the visualisation of the 25th Kalki King Raudra Chakrin, sitting in the central courtyard of his palace at the centre of Shambhala. The king takes on the appearance of a mighty warrior. As the emanation of Manjushri, meditating on Raudra Chakrin is very beneficial. In one of the prayers below, the Panchen Lama mentions Shambhala as a physical location, a pure land and at the same time, a symbol of the spiritual attainment granted through the Kalachakra practice.

SHAMBHALA PRAYER

By His Holiness the 6th Panchen Lama Lobsang Palden Yeshe

Homage to the kind spiritual master

Inseparably one with glorious Kalachakra,

Who has attained to the state of the empty body,

With the great unchanging bliss possessing all excellences

In constant embrace with the beautiful dharmadhatu lover.

To the north of India lies the fabulous land of Shambhala,

With the city of Kalapa a jewel at its heart.

There at its centre, seated on a throne studded in gems,

As though riding a magical flying horse

Is Raudra Chakrin, Wrathful Holder of the Wheel.

I call to him, an embodiment of the Three Jewels:

Come forth with your weapon of inconceivable wisdom;

Slay from within me my every delusion

And my habit of grasping at a truly existent self.

Bless me that I may behold you in Shambhala,

Wisely guiding your throngs of devotees.

And when the time comes to tame the barbarians,

May you keep me in your inner circle.

Should I die before achieving enlightenment

May I be reborn in Shambhala, in the city of Kalapa,

And have the good fortune to drink the honey

Of the sublime teachings of the kalkin masters.

May I take to completion the profound non-dual message

Of the two yogic stages of tantric practice as taught in Guhyasamaja, Yamantaka, Heruka Chakrasamvara and Kalachakra;

Thus in this very lifetime may I achieve realisation of

The clear light and illusory body in perfect union,

Or the empty body conjoined with the unchanging bliss.

Source: Mullin, Glenn H. The Practice of Kalachakra (pp. 150-151). Shambhala. Kindle Edition.

About Tashi Lhunpo Monastery

Tashi Lhunpo Monastery was built by His Holiness the 1st Dalai Lama, Gedun Drub, with financial help from local nobles, in 1447. The name Tashi Lhunpo means “heap of glory” or “all fortune and happiness gathered here”. The great monastery is located in Shigatse, in the Tsang Region, the second most important cultural city in Tibet after Lhasa.

The 5th Dalai Lama offered Tashi Lhunpo Monastery to his teacher, the 4th Panchen Lama, and since then, the monastery has been the official seat of the Panchen Lama’s line of incarnation. The 4th Panchen Lama raised funds and expanded Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, and due to his efforts, Tashi Lhunpo Monastery was accorded a status equal to the three great Gelug monasteries: Gaden, Sera, and Drepung.

The Gorkha Kingdom (the present-day Nepal) invaded Tibet, captured Shigatse, and ransacked Tashi Lhunpo Monastery in 1791

After the passing of the 6th Panchen Lama, the Gorkha Kingdom (the present-day Nepal) invaded Tibet, captured Shigatse, and ransacked Tashi Lhunpo Monastery in 1791.

It was fortunate that the 6th Panchen Lama had built a strong rapport and goodwill with China, as Emperor Qianlong sent his army to Tibet, and the combined Qing and Tibetan army defended Tibet and forced the Gorkha army out as far as the outskirts of Kathmandu. The Gorkha were also forced to sign a treaty to maintain peace and pay tribute every five years. Most importantly, the Gorkha were forced to return whatever they looted from Tashi Lhunpo.

The magnificence of Tashi Lhunpo Monastery has continued to impress visitors for hundreds of years after it was first built. According to Captain Samuel Turner, an East India Company officer who visited the monastery in the 18th century:

“If the magnificence of the place was to be increased by any external cause, none could more superbly have adorned its numerous gilded canopies and turrets than the sun rising in full splendour directly opposite it. It presented a view wonderfully beautiful and brilliant; the effect was little short of magic, and it made an impression which no time will ever efface from my mind.”

Source: en.wikipedia.org

At one point, Tashi Lhunpo Monastery was the residence of over 4,000 monks. It consisted of four Tantric Colleges, and each college had its own abbot. These four abbots held the primary responsibility to search for the next reincarnation of the Panchen Lama after his death.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guards ransacked Tashi Lhunpo Monastery and burnt holy scriptures it contained. They also opened the reliquary stupa of the 5th and 9th Panchen Lamas, threw their relics into the river, and damaged the monks’ quarters. The residents of Shigatse managed to save some of the 5th and 9th Panchen Lama’s remains. However, Tashi Lhunpo Monastery fared better than other religious structures in Tibet because the 10th Panchen Lama chose to remain in Tibet.

In 1985, the 10th Panchen Lama commenced the construction of a new reliquary stupa to house the remains of the 5th and 9th Panchen Lamas. On January 22, 1989, the 10th Panchen Lama consecrated this stupa before he himself entered clear light six days later at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery.

Today, the magnificent Tashi Lhunpo Monastery stands on 150,000 metre2 (15 hectares) of land and is surrounded by a 3,000 metre (9,842 ft) long wall. The monastery complex contains 58 Sutra Chapels and approximately 3,600 rooms. A unique feature of Tashi Lhunpo Monastery is that most of the structures in the complex have golden glazed tiles and interlaced walls. Many pilgrims come to circumambulate the monastery because it is considered a holy site.

The main features of Tashi Lhunpo Monastery are:

- The great statue of Maitreya in the Maitreya Temple which was built by the 9th Panchen Lama. The statue is 26.2 metres (85.9 ft) high and 11.5 metres (37.7 ft) long. The lotus foundation alone is 3.8 metres (12.5 ft) high. The statue is also adorned with precious jewels and gold and brass coating.

- The reliquary stupas of the previous Panchen Lamas, where visitors can read the achievements of each Panchen Lama carved on the surrounding walls.

- The Panchen Lama Palace, or the White Palace, which contains embroidered silk thangkas that relate the events in the lives of the Panchen Lamas, together with many inscriptions. However, the living quarters of the Panchen Lama are not open to the public, thus visitors should be content with the small halls in front of the palace.

- The Thangka Exhibit Platform which celebrates the birth, enlightenment, and parinirvana of Buddha Shakyamuni. The platform was originally built in 1468 under the supervision of the 1st Dalai Lama. The Thangka Exhibit Platform is a special symbol of Shigatse, and is 32 metres (104.9 ft) high and 42 metres (137.7 ft) long.

- Various other chapels and halls, including the magnificent Dorje Shugden chapel.

Thangka Sunning Festival at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery

Every year, from May 14-16, Tashi Lhunpo Monastery holds a Thangka Sunning Festival. This event culminates each day with the unveiling of three thangkas. On the first day a thangka of the Buddha Amitabha (who gained enlightenment in a previous aeon) is unveiled, reminding practitioners to cherish the Dharma they have received in the past. On the second day, a thangka of Buddha Shakyamuni (the present Buddha) is unveiled, to remind people to engage in virtuous actions and practice the Dharma now. On the third day, a thangka of Maitreya (the future Buddha) is revealed to remind practitioners to think of their future rebirths, and remind them to make auspicious prayers to progress on their spiritual practice. It is said that every year, the event attracts over 20,000 followers.

Introduction to the Kalachakra Tantra

The Kalachakra is one of most advanced Tantric practices that were brought from India to Tibet. Kalachakra means the “cycles of time”. The tantra explains both universal and spiritual progress through the use of three cycles:

- External cycle

- Internal cycle

- Alternative (spiritual) cycle

A Kalachakra sand mandala

These three cycles are included in the five chapters of the Kalachakra Tantra. The first and second chapters are known as Ground Kalachakra.

- Chapter 1 contains information about the outer or physical Kalachakra or cycle. This includes information about the Kalachakra calendar system, the working of elements, our solar systems, and the death of the universe.

- Chapter 2 contains information about the inner Kalachara, and the functions and classifications of the human body and its experiences. The human body consists of several components such as the winds, channels, and drops, while the human experience is described as waking, dreaming, deep sleep, and the energy of sexual orgasm.

The third to fifth chapters are known as the Path and Fruition.

- Chapter 3 contains information about the preparation for meditational practice, which is the Kalachakra initiation.

- Chapter 4 explains the actual meditation practice on the mandala, the deities in the generation stage practices, and the completion or the perfection stage of the Kalachakra’s Six Yogas.

- Chapter 5 describes the fruit of the practice, the state of enlightenment.

How the Kalachakra Tantra Went from India to Tibet

The Kalachakra Tantra reached India through the efforts of a great saint named Kalachakrapada the Elder. It is said that one day Manjushri, who was Kalachakrapada’s yidam (meditational deity) appeared to him and entreated him to travel to the north of India. There, he encountered the Kalki King Aja who is considered to be an emanation of Yamantaka. King Aja bestowed upon him the complete initiation and commentary to the Kalachakra practice. Therefore, Kalachakrapada became the first in the line of Indian masters who propagated the practice.

After he returned to India, Kalachakrapada defeated the abbot of Nalanda Monastery, Naropa, in a debate and initiated him into the practice of Kalachakra. Naropa then legitimised the practice of Kalachakra in Nalanda and initiated great masters, such as Atisha, into the practice.

There are two main lineages of the Kalachakra Tantra that came to Tibet: The Ra and the Dro lineages. The Ra lineage descended from Samantashri, a Kashmiri master, and Ra Lotsawa Dorje Drak, a Tibetan translator. Prominent Sakya masters such as Drogon Chogyal Phagpa (1235-1280), Sakya Pandita (1182-1251), Buton Rinchen Drup (1290-1364), and Dolpopa Sherab Gyeltsen (1292-1361) practised the Ra lineages.

The Dro lineage descended from Somanatha, another Kashmiri scholar who travelled to Tibet, and translator Dro Lotsawa Sherab Drak. The Dro lineage was widely practised within the Jonang School. A famous Jonang scholar, Taranatha, wrote a commentary to the Dro lineage of Kalachakra. Both Buton Rinchen Drup and Dolpopa Sherab Gyeltsen were holders of Kalachakra Tantra from both the Ra and Dro lineages.

The Kalachakra Tantra came to the Gelug school through Lama Tsongkhapa. It is said that Lama Tsongkhapa had a pure vision of Kalachakra and auspicious signs while examining this Tantra. The deity put his primary hands on Lama Tsongkhapa’s head and declared, “Concerning the Kalachakra Tantra, you have appeared like King Suchandra himself.” One of Lama Tsongkhapa’s main disciples, Khedrup Je, who would later be recognised as the 1st Panchen Lama, wrote a commentary to the Kalachakra Tantra.

Today, the Kalachakra Tantra is practised by all Tibetan Buddhist schools, and prominently featured within the Gelug lineage.

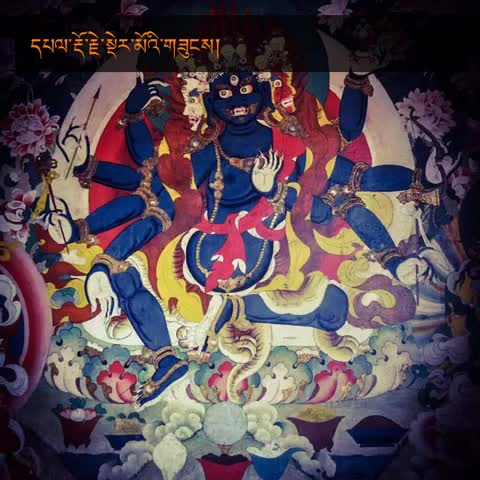

Iconography of Shri Kalachakra

The following are the main features of Shri Kalachakra’s iconography:

- His body is blue in colour.

- He has four faces. The main face is blue-black, with a fierce expression and bared teeth. The face on the right is red in colour with a desirous expression. The face on the left is white with a peaceful expression. Finally, the face on the back is yellow in colour and in Samadhi. Each of the faces has three eyes.

- His hair is tied and adorned with vajrasattva, vishvavajra, and a crescent moon as a crown.

- Kalachakra wears include Vajra earrings, necklaces, bracelets, a Vajra jewel, anklets, belt, mala, and a loose tiger skin skirt.

- He has six pairs of shoulders. The first and second pairs on the left and right are blue. The third and fourth pairs are red, and the fifth and sixth are white.

- Of his twelve upper arms, the first four arms (left and right) are black in colour, the second four arms are red, and the third four arms are white.

- On his twenty-four hands, all the little fingers are green, the ring fingers are black, the middle fingers are red, the index fingers are white, and the thumbs are yellow. All the fingers are radiant and beautiful.

- In his twelve right hands, the first four black hands hold a vajra, sword, trident, and a curved knife. The four red hands hold a flaming arrow, vajra hook, a rattling damaru, and a hammer, while the four white hands hold a wheel, a spear, a stick, and a battle axe.

- In his twelve left hands, the first four black hands hold a vajra bell, shield, Katvanga, and a blood-filled skull cup. The four red hands hold a bow, vajra, lasso, jewel, and a white lotus, while the four white hands hold a conch, a mirror, a vajra chain and the four-faced head of Brahma adorned with a lotus.

- The right leg is extended and red in colour. It steps on a being named Kamadeva who has four hands and one face. Kamadeva’s four hands hold five flowers, a bow, a lasso, and a hook.

- The left leg is white, and steps on a being named Rudra, who has a white face, four arms, and three eyes. The four arms hold a trident, damaru, a skullcup, and a katvanga.

- Holding the soles of Kalachakra’s feet are two demons, Uma and Rati, who lie in a woeful position.

The following are the main features of Vishvamata’s (Shri Kalachakra’s consort) iconography:

- Her body is yellow in colour.

- Her four faces, from right to left, are the colours yellow, white, blue, and red. Each face has three eyes.

- Her four right hands hold a curved knife, a hook, a rattling damaru, and a bead mala.

- In her four left hands are a skull cup, a lasso, an-eight-petal lotus, and a jewel.

- Her crown holds an image of Vajrasattva.

- Her left leg is extended.

Shri Kalachakra and Vishvamata reside in the centre of the Kalachakra mandala. The weapons and shield held by Shri Kalachakra represent triumph over Mara, and his ability to protect sentient beings. Robert Beer, researcher of symbolism mentioned the following regarding the weapons held by the deities:

“Many of these weapons and implements have their origins in the wrathful arena of the battlefield and the funereal realm of the charnel grounds. As primal images of destruction, slaughter, sacrifice, and necromancy, these weapons were wrested from the hands of the evil and turned – as symbols – against the ultimate root of evil, the self-cherishing conceptual identity that gives rise to the five poisons of ignorance, desire, hatred, pride, and jealousy. In the hands of siddhas, dakinis, wrathful and semi-wrathful yidam deities, protective deities or dharmapalas, these implements became pure symbols, weapons of transformation, and an expression of the deities’ wrathful compassion which mercilessly destroys the manifold illusions of the inflated human ego”

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Kalachakra Practice

The 11th Panchen Lama giving Kalachakra initiation to a mass audience

The Kalachakra Tantra is unique because of its tradition of being delivered to a mass audience. It is said that practising Kalachakra creates the cause for one to be born in Shambhala. The benefits to be reborn in Shambhala are so that one can continue spiritual practice without disturbances. The Kalachakra initiation enables practitioners to practice yoga as described in the Kalachakra Tantra with the aim of achieving the state of Shri Kalachakra.

Requirements and Motivation

To be properly initiated in Kalachakra practice, the teacher and disciple should meet certain qualifications. According to the 4th Panchen Lama, Lobsang Chokyi Gyeltsen, the qualification of a teacher is as follows:

“He should have control over his body, speech, and mind. He should be very intelligent, patient, and without deceit. He should know the mantras and tantras, understand reality, and be competent in composing and explaining texts”

Source: dalailama.com

The student should have experienced, or at least have intellectual understanding and appreciation of the three principal aspects of the Mahayana path:

- Renunciation of samsara

- Bodhicitta

- Understanding of emptiness

Out of the three, the most important is Bodhicitta, which should be the primary reason for one to be initiated. In the Abhisamayalankara text, Lord Maitreya defined Bodhichitta as “the desire for true, perfect enlightenment for the sake of others.” In the context of Kalachakra, practitioners should have the following motivation:

“For the sake of all sentient beings, I must achieve the state of Shri Kalachakra. Then I will be able to establish all other sentient beings in the state of Shri Kalachakra as well”

Source: dalailama.com

Overall, there are eleven initiations within Kalachakra practice. The first seven initiations are considered the first set, and are about preparing for generation stage meditation in Kalachakra. The second set, the remaining four initiations, are to prepare for the completion stage meditations. Those who do not have any intention to practice Kalachakra are only given the first set of initiations.

Western Perspectives of Shambhala

For hundreds of years, westerners have been fascinated with Shambhala. The ideas of early westerners about Shambhala were based on fragmented accounts from the Kalachakra Tantra. The first known western account of Shambhala was from Estevao Cacella (1585-1630), a Portuguese Jesuit Missionary. Cacella is said to have come across references to Shambhala, which he pronounced as Cembala. He tried to find the kingdom but was unsuccessful.

In 1833, a renowned Hungarian scholar, Sandor Korosi Csoma (1784-1842), who was one of the first Europeans to learn the Tibetan language, read the Kangyur, and put together the first Tibetan-English dictionary. After this, he wrote an article about Kalachakra, and in this article he mentioned Shambhala. According to Csoma, this mystical land was located between 45′ – 50′ north latitude, which pointed to an area of low mountains, lakes, and green hills in eastern Kazakhstan. After spending many years travelling, Csoma planned to go to Lhasa in 1842, but unfortunately he contracted malaria, and died before his wish was realised.

In the 1860s, a German national named Schlagintweit wrote a book titled “Buddhism in Tibet” in which he mentioned Shambhala. In the 19th century, the founder of the Theosophical Society, Blavatsky, who claimed to be in contact with the Himalayan adepts, mentioned Shambhala as a great spiritual land without giving it special emphasis.

American author Alice A. Bailey (1907–1942) mentioned that Shambhala was “an extra-dimensional or spiritual reality on the etheric plane, a spiritual centre where the governing deity of Earth, Sanat Kumara [lives].”

Alexandra David-Neel, a French Buddhist explorer associated Shambhala’s location with Balkh, which is the present-day Afghanistan. John, G. Bennett, a British Mathematician speculated that Shambhala was a Bactrian sun temple named Shams-i-Balkh. In the 1930s, several science fiction novels mentioned Shambhala, including one of the most famous, James Hilton’s Lost Horizon.

Expeditions in Search of Shambhala

The fascination that westerners had with Shambhala did not stop at mere speculation. Several of them initiated expeditions in search of this hidden paradise. However, none of these expeditions provided conclusive evidence about the physical location of Shambhala.

The Roerich Expedition

Nicholas and Helena Roerich

In 1925 – 1928, Russian explorers Nicholas and Helena Roerich led an expedition to the Altai Mountains in search of Shambhala. The Roerichs believed that Shambhala was the source of all Indian spiritual teachings, including the power of fire (agni) for purification which originated from the earliest Hindu spiritual texts, the Vedas. For them, Shambhala was a land of peace and spiritual practice. The Roerichs established a spiritual system based on their beliefs called Agni Yoga.

The Bolsheviks

Tibet Road in the Himalayas, photographed in 1867 by Samuel Bourne

In the 1920s, Russian writer, chief Bolshevik cryptographer, and one of the most influential leaders of the Soviet Secret Police, Alexander Barchenko, initiated an expedition to search for Shambhala in order to retrieve wisdom from its inhabitants. Their goal was to synchronize the Kalachakra Tantra with Communism. They planned to embark on an expedition to Inner Asia in search of the hidden paradise. However, due to political intrigue, this plan did not go through. In 1924, the Soviet Foreign Commissariat sent a rival expedition to Tibet instead, which was not successful.

The Agharti/Shambhala Expedition

![An artist illustration of Agharti]](https://www.tsemrinpoche.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Shambhala038.jpg)

An artists illustration of Agharti

Inspired by two 19th century French novels that mentioned a place called Agharti, a Polish captain named Ossendowski and an anti-Bolshevik Austrian-born Russian, Baron Ungern-Sternberg (1886 – 1921) searched for Agharti in Mongolia. Agharti was described as an underground kingdom whose inhabitants practised magic, and would emerge to help the residents of the world to overcome destructiveness and materialism. These two explorers confused Shambhala with Agharti, and using speculation from Blavatsky that mentioned Shambhala was located in the Gobi desert in Mongolia, they tried to find Agharti in Mongolia or Central Asia.

Laurence Brahm’s Expedition

In more recent years, author, political columnist, and international mediator Laurence Brahm embarked on an expedition to search for Shangri-La. His expedition is documented in the two-part documentary, “Searching for Shangri-La – Laurence Brahm, 2002 Expedition” and “Shambhala Sutra – Laurence Brahm, 2004 Expedition”.

Searching for Shangri-la — Laurence Brahm, 2002 Expedition

Or view the video on the server at:

https://video.tsemtulku.com/videos/SearchingForShangriLaLaurenceBrahm2002.mp4

In the first documentary, Brahm describes his frustrations with the modern hectic urban lifestyle in China. He then interviews various personalities in China (artists, singers, tourists, monks) about the meaning and location of Shangri-La. His search leads him to Lhasa, where he visits Jokhang Temple and several other places in the area.

Shambhala Sutra — Laurence Brahm, 2004 Expedition

Or view the video on the server at:

https://video.tsemtulku.com/videos/ShambhalaSutraLaurenceBrahm2004.mp4

In the second documentary, Brahm encounters “The Journey to Śambhala” (Śambalai lam yig) by the 6th Panchen Lama. He brings the old scriptures, and asks the monks and high lamas he encountered to explain to him about the directions to Shambhala based on the scriptures. He embarks on an expedition to search for Shambhala following the description in the 6th Panchen Lama’s book. The journey brings him to many remote and ancient places in Tibet, such as the ruins of the Guge kingdom and Mount Kailash. Finally, his quest leads him to seek an audience with the incarnation of Shambhala’s king, the 11th Panchen Lama from whom he received this precious advice:

“Help others with compassion even though it may bring loss to yourself. Then peace will come. If you cause damage to others due to your selfish actions or to fulfil your own aims, then there will be no peace in the world. Moreover, in my opinion, to make guns and weapons of mass destruction, other countries spend large sums of money… This will make the countries have more military power. But it will bring harm to the world. If these countries instead use the same money to buy medical equipment to help the sick and disabled people and support students or for medical research to close gaps between the rich and poor and between developed and underdeveloped nations, then the world will have more peace, and society will enjoy better development. But by investing money on military force and weaponry, it is equivalent to throwing wealth into a vast ocean. What a complete waste.” ~ The 11th Panchen Lama

Source: Brahm, Laurence, “Shambhala Sutra 2004 Expedition”, Discovery Publisher, 2004

Finally, the 11th Panchen Lama gave the following message to Laurence Brahm to bring to the rest of the world:

“First, I wish for peace to be with the world. People all over the world unite together to help each other and be filled with love. I wish people of different religions and beliefs may be tolerant with each other. Second, Tibetans both here and abroad should love their country and make efforts to develop their hometown economy, so as to improve living standards. Lastly, every day I will pray for the world in English:

I pray for peace in the world.

May Buddha bless human beings.” ~ The 11th Panchen Lama

Source: Brahm, Laurence, “Shambhala Sutra 2004 Expedition”, Discovery Publisher, 2004

Shangri-La in Yunnan Province, China

Another documentary about a city named Shangri-La, formerly known as Zhongdian, in Yunnan Province, China. The narrator mentioned that the location of Shangri-La is similar to the location of mystical land described in James Hilton’s best selling novel, Lost Horizon.

The Real Shangri-La: Everything You Didn’t Know | China Revealed | TRACKS

James Hilton’s Lost Horizon

Lost Horizon (1973)

Or view the video on the server at:

https://video.tsemtulku.com/videos/ShambhalaVid01LostHorizon1973-1.mp4

James Hilton (1900–1954), a British-American author, wrote about Shambhala or Shangri-La in his world-famous novel Lost Horizon in 1933. It is said that James Hilton was inspired to write this novel after reading an article in the National Geographic Magazine about Joseph Rock’s travels in the border regions of China and Tibet. Lost Horizon tells the story of a group of people who board a plane to escape chaos in Central Asia. When their plane crashes, the group are stranded in the Himalayan region, and find a community at a Lamasery in a lost Tibetan valley called Shangri-La.

The book has inspired two blockbuster Hollywood movies with the same title. A high-end hotel chain, Shangri-La, was named after the hidden paradise in the book.

Introduction to James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon” by Tsem Rinpoche

Or view the video on the server at:

https://video.tsemtulku.com/videos/ShambhalaLostHorizonIntroduction.mp4

Click here to learn about H.E. Tsem Rinpoche’s introduction to James Hilton’s Lost Horizon

Transcript

There are many levels of existence, and there are many dimensions of existence, and they are numberless and countless. There are many realms of existence, dimensions of existence, and modes of existence. But within all these existences, there are numberless amounts of sentient beings. There is no count. When people refer to a realm, they always talk about the human realm. But that’s very limited, that’s a speck in the vastness of the galaxy. And within that speck you have various dimensions, you have various levels of existence. All of this in Buddhist terminology you call Samsara. So Samsara is not about seven billion people on the planet, it’s much more than that. So that is why when we refer to benefiting sentient beings we are talking about innumerable, numberless sentient beings, because they are so vast in number you don’t actually have a count of them.

It is said only a Buddha has the omniscience to perceive how many exact sentient beings there are. But it is certain that the amount of sentient beings is much more than the grains of sand on every single beach on this planet. Now, within this planet we have very different dimensions. For example, we are right now in Kechara Forest Retreat. We are existing in one dimension, but simultaneously, there are spirits, land gods, and nature devas. They exist. They are in another dimension but we exist simultaneously. Sometimes we cross paths, and we can see each other; sometimes we don’t. But just because we don’t see them, it doesn’t mean they are not existing right here. So they can be existing in the same dimension, and we can cross sometimes. So therefore, the amount of beings that exist in different types of dimensions, in different modes of existence are quite diverse, innumerable and without count.

Now, in Buddhist terms, when we talk about a pure land such as Sukhavati, the western paradise of Amitabha Buddha or we talk about Tushita (dga’ ldan yid dga’ chos ‘dzin) the Paradise of Maitreya, or we talk about Kechara, or the paradise of Heruka or Yamantaka, or the paradise of Manjushri, Chenrezig Avalokiteshvara (such as Potala), or Akshobhya Buddha and so on, those are places that you travel to with the mind, or in other terminology, with the consciousness or soul. So those places you ascend mostly with your consciousness. There are exceptional cases where people ascend to Kechara Paradise with their very bodies and transform. The reason for that is because the bodies are made up of four elements so the rougher, grosser elements become lighter and they become even more lighter elements such as light. But on this planet, we also have many types of existences. Existences and places where nagas exist, the places where yakshas and rakshas exist, the places where spirits exist, and they are simultaneous with us. Spirits can have a little community and they can be living right next to you, you won’t see them. But they are still existing in the same space as you but on a different dimension. I repeat, they exist in the same space as you but on a different dimension. Hence, many types of beings can exist and live in one spot, and you don’t crisscross.

Shambhala is said to exist within the Himalayan Mountains

Now there’s a pure land that is physical, that you can actually go to on this planet. And it is called Shambhala. Shambhala is a pure land that is said to exist within the Himalayan mountains. You have to understand the Himalayan mountain range is massive. It’s just huge, and it’s massive and most of it is unexplored because people simply just can’t get there. So within the Himalayan mountain range, which is Karakorum, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tibet, Nepal, China (part of it), India – this whole area is surrounded by these countries, and within these countries, it’s the Himalayan region. So the Himalayan region expands to most of Tibet if not all of Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, North India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, parts of China, and maybe Nepal.

So this is the Himalayan range, and it is massive. Now, there are people living there, there are animals living there, there are Yetis living there, there are birds living there, there are insects, there are microscopic animals or beings living there. They have a different way of existence because of the cold. They have a different way of functioning and eating and defecating, and sleeping, and procreating, because of the cold but they still exist. Now, within that Himalayan range or region of land, is where Shambhala is said to be located. Now, Shambhala is a place that is surrounded by mountains, but the people in the city live in the valley. Because they live in the valley, they get very fresh water from the mountains that is snow-capped. So the snows melt and they get fresh water.

And the people who live there, they grow their own food, it is said that they are vegetarian, and they eat grains, they eat vegetables, they don’t eat rough, fleshy, bloody food. They eat very light, natural food they grow, so it is very healthy for their body. There are no toxins and pollution there because they don’t have modern amenities such as electricity, cars, you know, petrol usage, they don’t have oil usage, they don’t have anything that leaves a footprint in the environment and damages the environment. And also, everything they have, everything they do there, it is generated within themselves. But it is said because the valley is extremely well located, and I am talking about in a geographical sense, where the sun comes at the right time, the seasons come at the right time, and also there’s water there, there’s heat, there’s moisture, there’s also dryness, there’s lakes and all that. So a lot of things there grow naturally, spontaneously because of the geographical configuration. You see in some parts of our planet, things just grow very easily, there are some places on our planet where nothing grows or it is very difficult to grow.

So that is the geographical configuration of the location. And the people who live there are basically a monarchy, and they are ruled by saintly kings one after another. Now, this becomes a little mythological, but the kings are said to be emanations of Lord Manjushri. So, of these kings, the first king actually left the kingdom and he went to Lord Buddha. He heard about Lord Buddha’s fame and he went to request and receive teachings from Lord Buddha. And among the many teachings that Lord Buddha had conferred on him, was the famous tantra of Kalachakra. The famous inner, outer and secret Kalachakra Tantra that was conferred to him, and he took the tantras of Kalachakra and he also took the teachings of Buddha and went back to the Shambhala Kingdom, and he practised it, and he was said to have gained very high realisations.

And after that he taught his kingdom; he taught his ministers; he taught the people that were interested; and therefore a lot of qualified masters were produced during his time. Which after this king passed away, the next generation taught it, and the next generation taught it. Mind you, they live for hundreds of years. How many hundreds of years, the scriptures vary, some say 500 to 600 years, some say 100 to 200 years, it differs.

So in their place, things grow very easily. It is always green. This place doesn’t freeze over. They have plenty of water. They have plenty of sunshine. They are protected by a ring of mountains. And it is said that when you travel, some travellers have come across the entrance. The entrance is marked, there are markings to find the entrance. But it is said that you have to have a very strong karmic affinity to be able to find this place. So you can literally get your trekking gear, you can literally get your trekking stuff, and you can trek to the mountain to find them because people in the past have done that and have found the entrance. Some go in and stay, some go in and come back and tell us about it.

And so people there live very long lives. There, they don’t have any diseases as we know. They don’t have greed because their society is not based on money. It’s not based on acquisition. It’s not based on material things. Things grow, so people help each other to build houses, they live together, they produce their own clothes, so there is no need for greed, and there is no need for acquisition or materialism because everything they have, they share. It’s just like some of the ‘primitive people’ we see today still living in South America, in the Philippine islands, and some of the Caribbean islands. They don’t have greed. You know they live as a community, sorry to say they kill a pig in the forest, they share the pig, they share their clothes, they share whatever grows. There is no sense of I own this, I own that, I own this. You know what I mean? So that does exist in the outside world, outside of Shambhala. So in Shambhala there is no sense of greed because people share their resources, and there is no acquisition of wealth. They basically have families, they get married, they grow vegetables, they have arts, they have music, they have singing, they write books, and on top of that they study the Dharma and they practice the Kalachakra Tantra in particular.

Now, how can someone go there? You can physically go there if you have the directions or you can astrally travel there. In the Tibetan tradition, there have been many lamas, who have astrally travelled to Shambhala and came back to give a very strong and very clear and accurate description. One of them was His Holiness the Panchen Lama. The Panchen Lama’s line of incarnations are considered the emanations of one of the kings of Shambhala, so he has a very strong connection to Shambhala. And in Tibet, there was a very strong tradition of His Holiness Panchen Lama giving Kalachakra teachings and initiations to people, and it was highly sought after because he was considered the emanation of their king.

So therefore, inadvertently, the Kalachakra teaching became associated with Shambhala. They were not associated initially. Kalachakra is a teaching, and Shambhala is a place. But because the king went to receive teachings from Lord Buddha Shakyamuni, and he practised it, it then became inadvertently associated. So, now this Shambhala, there are few Tibetan texts that talk about it. There are few Tibetan texts that talk about how to get there, and there are few Tibetan texts that talk about how to meditate and astrally get there. And there are very renowned, famous, well known, learned lamas who tell you they travel there psychically or they travel there astrally. So when someone of that calibre like Panchen Lama tells you, it’s hard to doubt him because everything else he does is nearly perfect.

So, if someone like Jack Ma told you if you do this you’ll get rich, I mean, we will do it because he has a reputation of making things successful, right? So you know, if Tsem Rinpoche told you this is how you will get rich, you say ok, let’s research it first, because I don’t have a reputation of doing well in business. But if Jack Ma tells you, why not? So the Panchen Lama is like the Jack Ma of Buddhism. If he tells you it exists, you don’t doubt because he has done so much already. So therefore we can visit Shambhala or go there in two ways, physically, because it is a physical place, people can find it, and it’s a place that you can travel astrally if you are physically unable to go due to age, or, you know, you have disease because not everybody can walk through the snow. So, Kalachakra is associated with Shambhala in that way in a nutshell.

We can also make prayers to take rebirth in Shambhala. What’s the benefit of taking rebirth in Shambhala? You are a human, you are on this earth, you eat, you sleep, you defecate, you get old, you also die but you live a very long life because it’s a very peaceful place, it’s a very quiet place, it’s a spiritually charged place that is free of greed. So a lot of human aggression, a lot of human negative aggression and greed and anger and all that is hardly in existence in Shambhala. Does it mean that everybody in Shambhala is a Buddha? No, it doesn’t mean that, it just means that it’s a place that doesn’t breed and encourage those kind of actions.

Path to Shambhala, a painting by Nicholas Roerich

So, there are communities throughout the planet earth where people’s greed and people’s materialism is much less because the society doesn’t support it. It’s very simple, ok? Now, once you go there what do you do? You live just like we live here but we have less problems, less sickness to bear with, almost none, we have less materialism, less fighting, less danger, and it’s a very beautiful, natural place to live, no toxins, no pollution.

So, Tibetan lamas, Mongolian lamas, Nepali lamas, Bhutanese lamas, Indian Mahasiddhas, Indian great masters, basically in the Himalayan region, Himalayan kingdom, renowned people have talked about this place over and over and over again. Everybody cannot be lying. One of the biggest promoters of this region in the western world was Nicholas Roerich, who named this movement the Shambhala movement and he wanted to visit this place, he wrote about it and he told people in Russia where he was from, and in the west it became a new age thing now where such a holy place exists in the world. So Nicholas Roerich in the western world was renowned for promoting the land of Shambhala. And he didn’t see it as a mystical land. He saw it as a spiritually potent land where you can really go.

Song of Shambhala, a painting by Nicholas Roerich

So, is it good for us to take rebirth there? Of course, it is. If we can take rebirth there, why not? Why not? So how do you take rebirth there? Well, you can pray to the kings there, you can pray to the kings, focus on the kings, ‘May I take rebirth there’ You can focus on Shambhala itself and think ‘May I take rebirth there’ You can focus on Kalachakra Buddha and say ‘May I take rebirth there’ You can focus on Shakyamuni and you think ‘May I take rebirth there’ So taking rebirth there is just a wish.

Now, because the Himalayan lamas have talked about this for 2,500 years, the west has heard about it. So, there’s this person who [inspired] the Shangri-La hotel, chain of hotels back in the 30s, James Hilton. Shangri-La hotel was named after the legendary land featured in James Hilton’s Lost Horizon. He was a very intelligent man and he was a writer and he heard about this. So he wrote a very famous book, which I have, I’ll show you, it is called Lost Horizon.

Now, James Hilton never went to Shambhala but he heard about it from whomever, and he made up his own story based on the eastern stories about that and he wrote a beautiful little short book that two movies have been made from. A movie back in, a black and white one, back in the 50s I think, the 40s which I have, and one in the 70s and they are called Lost Horizon. But the movies are based on Shambhala and they are similar to Shambhala, but the plot changes of course. So, a synopsis of the movie Lost Horizon, which is one of my favourite movies, is a group of people are trying to escape from wherever it was, China, and they were westerners, they were missionaries, and they were diplomats, and there were some turmoil going on at that time because this was written in the 30s.

And so they got into a plane, and the plane crashed-landed in the Himalayas, and everybody in the plane minus the pilot survived. And so they were all in the plane and each of them, the characters had their own neurosis, they had their own fears, they had their own issues. And so they were in the middle of the Himalayas, they don’t know how they would survive, and then they were stuck there overnight, then what they see is a bunch of lamas, monks, lamas, with torches coming and they are rescued. And the lamas came to the airplane and rescued them, and took them back. They had to trek through the snow for a few days, they took them back to Shangri-La, the entrance, and they arrived at Shangri-La, there’s a marking, as it is said in the scripture, and then they entered a huge massive cave. The cave has two entrances, you enter and you exit, or you enter you exit.

So, they entered this massive cave, and as they pass through the cave, the cold starts to diminish. When they arrived at the other side of the cave, there is a huge opening and they look out, it’s the land of Shambhala, green with monasteries, with birds, with lush vegetation, beautiful, youthful people walking around, calm, quiet, no cars, no airplanes, no machineries, and everybody’s so welcoming. So the character, the main character is looking behind and he turns around he looks and guess what, there is all this snow, they look in front of him, and there is this lush valley and he just can’t believe where he is. So the lamas bring them down, to their monastery, and they treat them as guests. And they talk to them, and they give them food, they help them to heal. So each of them, one of the ladies in the book, the character was very unhappy with her life, she wanted to commit suicide. So the lama saved her life and talked to her and released her pain, released her guilt, released her feeling of emptiness, released her feeling of emptiness and loneliness because she ran around taking- she was a photo journalist- she ran around taking pictures of people getting killed, and shot and hurt so it affected her and she couldn’t live anymore, so by living in Shambhala, she healed herself and she wanted to stay.

Then there’s another person who was a comedian and he was a performer, and although he was doing ok, he wasn’t happy in the outside world, he decided to stay. So the movie focused on each character and their own personal issues and problems and how they all heal. There was only one person there who was not happy and he wanted to get out of Shambhala and so what happened was the main character, the main person in the book, was granted audience with the highest lama of Shambhala. So it’s very mystical, so they take him to all these dark chambers and he goes and he meets the high lama. The high lama in the book turns out to be like a Christian priest, a friar of some sort. But he doesn’t promote Christianity or anything, but he happens to be a missionary, who went there. And in the book, he formed Shambhala. Of course, that’s not what it is, but that’s the James Hilton version. But in any case, it’s quite mystical, and everything is very Tibetan, very Buddhist you know, and so he’s not talking about Christianity, he’s talking about universal compassion. He is talking about no greed. He is talking about love, being polite and working together creating harmony.

So what happens is this lama is dying, and he’s over 200 years old or whatever it is. And he needs to pass the leadership to this person that they have predicted will come. So he’s grooming this person to pass the leadership over to him and this person is having conflicts whether he should stay or not because he’s a high profile diplomat. And along the way, he falls in love with a lovely lady in Shangri-La and she never wants to leave, she wants to live there, she was brought there when she was very young. And then his brother who also wanted to leave also falls in love with another lovely lady in Shangri-La who wants to leave too. So there’s this conflict going on. And how they can leave is every two to three years, porters come from the outside world to deliver some goods. The real Shambhala doesn’t need porters. So in the book they have porters come. so when they come, you can follow the porters back to civilisation.

So what happened is the porters showed up, so this diplomat’s brother wants to leave, he doesn’t want to stay in Shambhala, he’s not interested. He wants money, he wants fun, he wants the cities. And this girl from Shambhala who they fell in love with each other wanted to leave also. So the lama said to him basically look, don’t take her out. If you take her out she is going to die because she is like a 100 years old. But she’s this beautiful woman, young with lush black hair, you know, you know just very vibrant and alive. And she’s telling the diplomat, look at me, do I have the skin of an old woman? Do I have the passion of an old woman? He’s like, no, you don’t look like an old woman at all. So anyway, the porters come, the brother convinces the diplomat to go with them. So the diplomat, the brother and this Shambhala girl, Shangri-La girl, leave with them and they go with the porters.

So the porters are very fast and they go ahead, and they are left behind so they shout “eh wait for us, wait for us, wait for us”, and they created an avalanche. And the avalanche carries away the porters and these three are stuck in the snowstorm. They are stuck in the middle of the Himalayas, but it’s actually filmed in Pasadena, California. They are stuck in this huge snowstorm. There are three of them, the girl from Shangri-La or Shambhala, whatever you prefer, the diplomat, and his brother, and the girl says I just can’t go on anymore, I am so tired, so they found a cave nearby, and they carried her, and when she arrived at the cave, she became an old woman. Her skin became wrinkled, her hair became white, and the diplomat realised everything the lama told them was true. That when you are in Shangri-La, your youth is preserved for a long time. The diplomat’s brother who didn’t believe that, was in shock because he said “They are lying to you, this girl isn’t a 100 years old, she’s young, look at her, we are going to go out and have a good time in New York, in Paris, Tokyo, we are not going to stay here.”

So in front of his eyes, he couldn’t accept it, he saw. So he ran out and he fell over the cliff. So the diplomat was stuck in the snow and he walked down to civilisation, and they put him in a hospital. So because he was a high diplomat, people had been sent to go and get him back to the western world, and when they came to his room in the hospital after he had recovered from dehydration and a little bit of frostbite, he ran away. And the end of movie is so beautiful because there’s singing and all that, he ran away and you see him arriving at the entrance of Shangri-La, because he is prophesied to take over as the next world leader for Shambhala after the old lama had passed away.

But in between all this, when they are inside Shambhala, what’s beautiful is that each one of them, each one of the characters goes through their own transformations. They become light, unmaterialistic, happy, they let go of all their burdens, they let go of all their stress, they let go of all their memories and they just become happy, they live there in simplicity. They live there in simplicity, in happiness, in pureness, and that’s what Shambhala is all about.