The Perfection of Concentration by Geshe Rabten

(By Tsem Rinpoche)

Concentration is important in both Dharma practice and ordinary life. The Tibetan word for the practice of concentration is zhi-nay (zhi-gNas). Zhi means peace and nay means to dwell; zhi-nay, then, is dwelling in peace or being without busyness.

If we do not carefully watch the mind it may seem that it is peaceful. However, when we really look inside we see that this is not so. Mind does not rest on the same object for even a single second. It flutters around like a banner flapping in the wind. No sooner does mind settle on one object than it is carried away by another. Even if we live in a cave on a high mountain the mind moves incessantly. When we are on the top of a tall city building we can look down and see how busy the city is, but when we are walking on the streets we are aware of only a fraction of the busyness. Similarly, if we do not investigate correctly we will never be aware of how busy the mind really is.

Primary consciousness itself is pure and stainless, but gathered around it are fifty-one secondary mental elements, some of which are positive, some negative and some neutral. Of these secondary elements, in ordinary beings, the negative ones are stronger than the positive. Most people never attempt to gain control of these secondary mental elements; if they did they would be amazed at how difficult such a task is. Because the negative elements have dominated the mind for countless lifetimes, overcoming them will require tremendous effort. Yet zhi-nay cannot be experienced until they have been totally subdued.

Thus the busyness of the mind is mind-produced. This means that a mental rather than a physical effort is required to eliminate it. Nonetheless, when engaging in an intensive effort to develop zhi-nay it is important to make use of certain secondary factors of a physical nature. For example, the place where one practises should be clean, quiet, close to nature and pleasing to the mind. And friends that visit should be peaceful and virtuous. One’s body should be strong and free from disease.

The practice of concentration requires sitting in your proper posture, to which there are seven points:

- Legs crossed and feet resting on the thighs, with soles turned upward. If this causes too much pain, it distracts from concentration. In which case, sit with the left foot tucked under the right thigh and the right foot resting on the left thigh.

- The trunk set as straight and erect as possible.

- Arms formed into a bow-shape, with elbows neither resting against the sides of the body nor protruding outward. The right hand rests in the left palm, with the thumbs touching lightly to form an oval.

- The neck straight but slightly hooked, with the chin drawn in.

- Eyes focused downward at the same angle as the line of the nose.

- Mouth and lips relaxed, neither drooping nor shut tightly.

- Tongue lightly held against the palate.

These are the seven points of the correct meditational posture. Each is symbolic of a different stage of the path. Also, there is a practical purpose in each of the seven:

- Having the feet crossed keeps the body in a locked position. One may eventually sit for a long period of time in meditation, even weeks or months in a single sitting. With legs locked, one will not fall over.

- Holding the trunk straight allows maximum functioning of the channels carrying the vital energies throughout the body. The mind rides on these energy currents, so keeping the channels working well is very important to successful meditation.

- The position of the arms also contributes to the flow of the energy currents.

- The position of the neck keeps open the energy channels going to the head and prevents the neck from developing cramps.

- If the eyes are cast at too high an angle the mind easily becomes agitated, if at too low an angle the mind quickly becomes drowsy.

- The mouth and lips are held like this to stabilize the breath. If the mouth is held too tightly shut, breathing is obstructed whenever the nose congests. If the mouth is help open too widely, breathing becomes too strong, increasing the fire element and raising the blood pressure.

- Holding tongue against the palate avoids an excessive build-up of saliva and keeps the throat from parching. Also, insects will not be able to enter the mouth or throat.

These are only the most obvious reasons for the seven points of the meditational posture. The secondary reasons are far too numerous to be dealt with here. It should be noted that the nature of the energy currents of some people does not permit them to use this position and they must be given an alternative. But this is very rare.

Although merely sitting in the vajra posture produces a good frame of mind, this is not enough. The main work, that done by the mind, has not yet even begun. The way to remove a thief who has entered a room is to go inside the house and throw him out, not to sit outside and shout at him. If we sit on top of a mountain and our mind constantly wanders down to the village below, little is achieved.

Concentration has two enemies, mental agitation, or busyness, and mental torpor, or numbness.

Generally, agitation arises from desire. An attractive object appears in the mind and the mind leaves the object of meditation to follow it.

Torpor arises from subtle apathy developing within the mind.

In order to have firm concentration these two obstacles must be eliminated. A man needs a candle in order to see a painting which is on the wall of a dark room. If there is a draught of wind the candle will flicker too much for the man to be able to see properly and if the candle is too small its name will be too weak. When the flame of the mind is not obstructed by the wind of mental agitation and not weakened by the smallness of torpor it can concentrate properly upon the picture of the meditation object.

In the early stages of the practice of concentration mental agitation is more of a hindrance than torpor. The mind is continually flying away from the object of concentration. This can be seen by trying to keep the mind fixed on the memory of a face. The image of the face is soon replaced by something else.

Halting this process is difficult, for we have built the habit of succumbing to it over a long period of time and are not accustomed to concentration. To take up the new and leave behind the old is always hard. Yet, because concentration is fundamental to all forms of higher meditation and to all higher mental activity, one should make the effort.

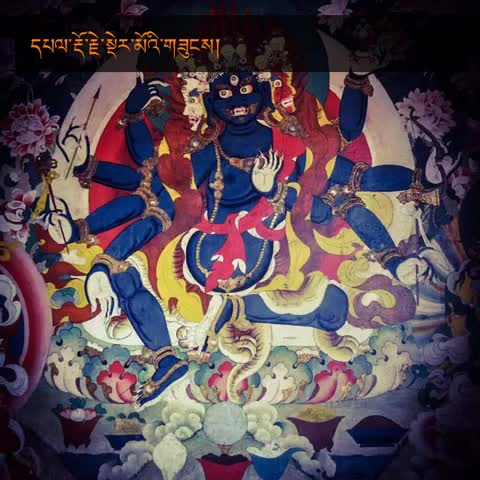

Mental agitation is overcome principally by the force of mindfulness and torpor by attentive application. In the diagram representing the development of zhi-nay there is an elephant. The elephant symbolizes the meditator’s mind. Once an elephant is tamed, he never refuses to obey his master and he becomes capable of many kinds of work. The same applies to the mind. Furthermore, a wild and untamed elephant is dangerous, often causing terrible destruction. Just so, the untamed mind can cause any of the sufferings of the six realms.

At the bottom of the diagram depicting the development of concentration the elephant is totally black. This is because at the primary stage of the development of zhi-nay mental torpor pervades the mind.

In front of the elephant is a monkey representing mental agitation. A monkey cannot keep still for a moment but is always chattering and fiddling with something, being attracted to everything.

The monkey is leading the elephant. At this stage of practice mental agitation leads the mind everywhere.

Behind the elephant trails the meditator, who is trying to gain control of the mind. In one hand he holds a rope, symbolic of mindfulness, and in the other he holds a hook, symbolic of alertness.

At this level the meditator has no control whatsoever over his mind. The elephant follows the monkey without paying the slightest attention to the meditator. In the second stage the meditator has almost caught up with the elephant.

In the third stage the meditator throws the rope over the elephant’s neck. The elephant looks back, symbolizing that here the mind can be somewhat restrained by the power of mindfulness. At this stage a rabbit appears on the elephant’s back. This is the rabbit of subtle mental torpor, which previously was too fine to be recognized but which now is obvious to the meditator.

In these early stages we have to apply the force of mindfulness more than the force of mental attentive application for agitation must be eliminated before torpor can be dealt with.

In the fourth stage the elephant is far more obedient. Only rarely does he have to be given the rope of mindfulness.

In the fifth stage the monkey follows behind the elephant, who submissively follows the rope and hook of the meditator. Mental agitation no longer heavily disturbs the mind.

In the sixth stage the elephant and monkey both follow meekly behind the meditator. The meditator no longer needs even to look back at them. He no longer has to focus his attention in order to control the mind. The rabbit has now disappeared.

In the seventh stage the elephant is left to follow of its own accord. The meditator does not have to give it either the rope of mindfulness or the hook of attentive application. The monkey of agitation has completely left the scene. Agitation and torpor never again occur in gross forms and even subtly only occasionally.

In the eighth stage the elephant has turned completely white. He follows behind the man for the mind is now fully obedient. Nonetheless, some energy is still required in order to sustain concentration.

In the ninth stage the meditator sits in meditation and the elephant sleeps at his feet. The mind can now indulge in effortless concentration for long periods of time, even days, weeks or months.

These are the nine stages of the development of zhi-nay. The tenth stage is the attainment of real zhi-nay represented by the meditator calmly riding on the elephant’s back.

Beyond this is an eleventh stage, in which the meditator is depicted as riding on the elephant, who is now walking in a different direction. The meditator holds a flaming sword. He has now entered into a new kind of meditation called vipasyana, or higher insight: (Tibetan: Lhag-mthong). This meditation is symbolized by his flaming sword, the sharp and penetrative implement that cuts through to realization of Voidness.

At various points in the diagram there is a fire. This fire represents the effort necessary to the practice of zhi-nay. Each time the fire appears it is smaller than the previous time. Eventually it disappears. At each successive stage of development less energy is needed to sustain concentration and eventually no effort is required. The fire reappears at the eleventh stage, where the meditator has taken up meditation on voidness.

Also on the diagram are the images of food, cloth, musical instruments, perfume and a mirror. They symbolize the five sources of mental agitation, i.e. the five sensual objects: those of taste, touch, sound, smell and sight, respectively.

Most people take the mental image of a Buddha-form their object of concentration in order to develop zhi-nay. First one must become thoroughly familiar with the object that one will focus on. This is done by sitting in front of a statue or drawing of the object for a few sessions and gazing at it. Then try sitting in meditation, holding the image of the form in mind without the aid of the statue or drawing. At first your visualization of it will not be very clear nor will you be able to hold if for more than a few seconds. Nonetheless, try to hold the image as clearly and for as long a period as possible. By persisting you will soon be able to retain the image for a minute, then two minutes and so forth. Each time the mind leaves the object apply mindfulness and bring it back. Meanwhile, continually maintain attentive application to see if unnoticed disturbances are arising.

Just as a man carrying a bowl full of water down a rough road has to keep one part of his mind on the water and another part on the road, in zhi-nay practice one part of the mind must apply mindfulness to maintain steady concentration and another part must use attentive application to guard against disturbances. Later, when mental agitation has somewhat subsided, mindfulness will not have to be used very often. However, then the mind is fatigued from having fought agitation for so long and consequently torpor sets in.

Eventually, a stage comes when the meditator feels tremendous bliss and peace. This is actually only extremely subtle torpor but it is often mistakenly taken to be real zhi-nay. With persistence, this too disappears. The mind gradually becomes more clear and fresh and the length of each meditation session correspondingly increases. At this point the body can be sustained entirely by the mind. One no longer craves food or drink. The meditator can now meditate for months without a break. Eventually he attains the ninth stage of zhi-nay, at which level, the scriptures say, the meditator is not disturbed even if a wall collapses beside him. He continues to practice and feels a mental and physical pleasure totally beyond description, depicted in the diagram by a man flying. Here his body is inexhaustible and amazingly supple. His mind, deeply peaceful, can be turned to any object of meditation, just as a thin copper wire can be turned in any direction without breaking. The tenth stage of zhi-nay—or actual zhi-nay, is attained. When he meditates it is as though the mind and the object of meditation become one.

Now the meditator can look deeply into the nature of his object of meditation while holding all details of the object in his mind. This gives him extraordinary joy.

Here, looking into the nature of his object of meditation means that he examines it to see whether or not it is pure, whether or not it is permanent, what is its highest truth, etc. This is the meditation known as vipasyana, or higher insight. Through it the mind gains a deeper perception of the object than it could through concentration alone.

Merely having zhi-nay gives tremendous spiritual satisfaction; but not going on to better things is like having built an aeroplane and then never flying it. Once concentration has been attained, the mind should he applied to higher practices. On the one hand it has to be used to overcome karma and mental distortion, and on the other hand to cultivate the qualities of a Buddha. In order to ultimately accomplish these goals, the object of meditation that it takes up must be voidness itself. Other forms of meditation are only to prepare the mind for approaching voidness. If you have a torch with the capacity to illuminate anything you should use it to find something important. The torch of zhi-nay should be directed at realization of voidness for it is only a direct experience of voidness which pulls out the root of all suffering.

In the eleventh stage on the diagram two black lines flow out of the meditator’s heart. One of these represents klesavarana, the obscurations of karma and mental distortion. The other represents jneyavarana, the obscurations of the instincts of mental distortion. The meditator holds the wisdom-sword of vipasyana meditation, with which he plans to sever these two lines.

Once a practitioner has come close to understanding voidness he is on his way to the perfection of wisdom. Prajna-paramita, the ultimate goal of the development of concentration.

(Translated by Gonsar Rinpoche. Prepared by Glenn Mullin and Michael Lewis. Printed in From Tushita, edited and published by Michael Hellbach, Tushita Editions, 1977.)

Source: http://www.abuddhistlibrary.com/Buddhism/A%20-%20Tibetan%20Buddhism/Authors/Geshe%20Rabten/The%20Perfection%20of%20Concentration/The%

20Perfection%20of%20Concentration%20by%20Geshe%20Rabten%20Rinpoche.htm

Geshe Rabten Rinpoche’s biography

“From the time I was a small child, I met monks in their maroon robes returning from the great monastic universities near Lhasa. I admired them very much. I also occasionally visited the large monastery in our region; and when I watched the monks debating, I was again filled with admiration. When I was about fifteen years old I began to notice how simple, pure and efficient their lives were. I also saw how my own home life, in comparison, was so complicated and demanding of tasks that were never finished. In order to be counted as a qualified monk in the nearby Dhargye Monastery, one had to spend at least three to four years studying and training one’s mind in the Buddha Dharma in one of the three monastic universities near Lhasa. With the thought of becoming such a monk in Dhargye Monastery, I decided at the age of seventeen to go to one of these monastic universities, although at that time I had no desire to become greatly learned in the Dharma”.

Extract from Geshe Rabten’s Biography, “Life of a Tibetan Monk”, Edition Rabten, 2000

When he was eighteen Geshe Rabten went on a three month journey from his birthplace in Kham in the Eastern province of Tibet to Lhasa in central Tibet where he became a monk in the monastic university of Sera. Very soon teachers and fellow students became aware of his magnificent character traits. While studying and meditating he went through unbelievable hardship. Hence teachers and fellow students gave him the name ‘Milarepa’. Due to his clear and precise way of logical debate, people compared him to Dharmakirti, the great Buddhist logical thinker. After having studied for about twenty years, he passed the Geshe exam in front of monks from the three great monasteries. He was given the title of the highest rank, ‘Geshe Lharampa’. This is the greatest honor, which is given by the examiners and by His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

In 1964 Geshe Rabten was chosen to be the philosophical assistant of the H.H. Dalai Lama. In 1969 the Dalai Lama first of all sent Western students to Geshe and then later, due to the amount of Western students that had accumulated he asked Geshe to move to the Tibetan monastery in Rikon, Switzerland to become the Abbot of that monastery. At that time Geshe had many students in the big monastic universities in India and as his master Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche was getting old and because Geshe did profess to have any interest in the comfort and money of the West, he would have preferred to have stayed in India. Only when his master pointed out that his teachings would be a great blessing to the people of the West did Geshe agree to go.

Geshe was the first Buddhist master to introduce the complete Vinaya-tradition and the original study of Buddhism to the West. Hence Geshe became the ‘path breaker’ of the complete and complex teachings of Buddhism in the West. Many masters, who are famous in the West today, were Geshe’s students, namely: Gonsar Rinpoche, Khamlung Rinpoche, Sherpa Rinpoche, Tomthog Rinpoche, Zopa Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe, Geshe Penpa, Geshe Tenzin Genpo, Geshe Thupten Ngwang, Geshe Thubten Trinley etc.

Almost unlike any other, Geshe Rinpoche was able to bring the essence of the thoughts of Buddha close to the listeners. No matter if the listener was from the West or the East, whoever followed his words felt all the unclearness disappear and in its place a clearness and calmness started to spread in one’s mind. His examples encouraged people to adopt a sincere way of acting. Whatever he explained, gave the pupil a feeling of hearing a description of the past, the future or of hearing deepest secrets as if all these things were in Geshe’s hand.

Geshe founded the center for higher Tibetan studies, Rabten Choeling at the lake of Geneva (originally Tharpa Choeling), the Tibetan center in Hamburg, Tashi Rabten at the Letzehof, Puntsog Rabten in Munich and Gephel Ling in Milan.

Source: http://www.rabten.at/GesheRabten_A1en.htm

Please support us so that we can continue to bring you more Dharma:

If you are in the United States, please note that your offerings and contributions are tax deductible. ~ the tsemrinpoche.com blog team

A profound teachings by Geshe Rabten the first Tibetan Buddhist master to introduce the complete Vinaya-tradition to the West.The Venerable Geshe Rabten Rinpoche was a Tibetan debater, scholar, and meditation master and he also as known as Milarepa. His teachings of how the mind operates and concentrates been explained. There’s so many knowledge to learn from/

Thank you Rinpoche for this great sharing.

Thank you Rinpoche, for this sharing which I found very useful knowledge . Some thing new for me and I am glad I came across this wonderful post. I have bookmarked this post to reread it from time to time till I could able to concentrate a single image of Buhhda better and to increase the strength of my focus. Its a good teachings from this post ,having all the methods, stages explained in such away all of us could understand how the mind works through diagrams of a story.

Rinpoche has mentioned that it is better to visualise virtuous object such as Buddha rather than any other object. Even the recent article that I’ve read here “The Supreme Path to the Three Kaya” https://www.tsemrinpoche.com/tsem-tulku-rinpoche/buddhas-dharma/the-supreme-path-to-the-trikaya.html , Geshe Thupten Lama mentioned that “All lamas agreed on this point!” (To concentrate on Buddha’s form).

Often, I heard Rinpoche describing the Buddha’s form in detail, such as Lady Vajrayogini, White Tara, Lama Tsongkhapa and so forth. It actually helped me visualising it better and then we just have to focus one part and make it bigger and bigger. But sadly, due to wordly activities, I have stopped doing that. Guess, I need to push up a bit. And this leads me to the point that Milarepa has once said, “The affair of the world will go on forever. Do not delay to practice the meditation. ”

Thank you Rinpoche for this article.

Rinpoche spoke about this subject matter rather simply in this teaching ( https://youtu.be/y3iXcAeGi3c?si=0WhB2GxacS8gM_1z ) , yet I find it profound. Very profound.

It should be done everyday and I didn’t. What a waste of time, but I will do it. Even if I can’t do it perfectly, I must try.

Thank you Rinpoche for this article.

This is my preliminary attempt to understand the profound process of concentration. I have recapped here a few points that I felt is important for me to take note off:

1. Our mind is fickle and cannot stay focus. Any attempt to keep it focus is daunting. “When we are on the top of a tall city building we can look down and see how busy the city is, but when we are walking on the streets we are aware of only a fraction of the busyness.”

2. Our primary consciousness is surrounded by 52 secondary mental elements; some negative, some positive, and some neutral. For us normal beings, the negative ones are the strongest.

3. Zhi Nay or concentration can only be achieved when one subdue the negative mental elements.

4. While the negative mental elements is a mental issue, a proper Vajra position can help practice concentration.The proper Vajra position comprises of 7 points which symbolizes the various stages of the path.

5. There are 2 enemies to concentration, they are (a) mental agitation, and (b) torpor. Agitation arises from desire. Torpor arises from subtle apathy developing within the mind. Mental agitation is overcome principally by the force of mindfulness and torpor by attentive application.

The blog post had so kindly provided a diagram to denote the stages of developing / cultivating concentration (Zhi Nay). I will certainly bookmark this and read it again.

Thank you Rinpoche for sharing this teaching from Geshe Rabten. I have learnt something new today.

Humbly, bowing down.

Stella Cheang

Dear Rinpoche,

This is a really interesting post. I like the illustration with the elephant and monkey as it describes the various state of our minds perfectly. Thank you for this beneficial post and may all attain the perfection of concentration.

With folded hands.

Wow! Too bad I missed this incredible blog post! It has a tremendous teaching and understanding of how the mind operates. I think that the Zhinay meditation as explained above gives a rather powerful roadmap of the stages of achieving control over the mind. I find it a rather powerful teaching and I think it is rather exciting because I guess, I need to develop better concentration especially on virtuous objects rather non-virtuous objects.

I think some time ago, Rinpoche did explain to me that all of us have powerful concentration, it is just selective especially to ourselves, the things we like. Most of the time, our concentration is expanded to objects and activities that are non-virtuous or that do not really bring us long term benefit and happiness. I guess that’s why I find these teaching to be particularly powerful and something I will need to read and re-read in order to develop the stages carefully.

This is my Master.

Thank You for sharing this Dear Rinpoche 🙂

im so happy and thankfull to have found Geshe Rabten now Tulku Rabten Rinpoche,His reincarnation 🙂

iam as often as i can in the Tashi Rabten Monastery in Austria,there is the Stupa of the venerable Geshe Rabten.

iam from Germany but its no problem for me to drive there and stay for a few days. If there are no obstacles in the next time,i will be there in September this year,i want to request for ordination to be a Monk.i ll write You.

Tashi Deleg

sincerelly Yours

alex

Dear Rinpoche

This article is to be translated to lamatsongkhapa.com

Warm regards

Valentina

Wow, Geshe Rabten! I read his book, The life of a Tibetan monk, last September, shortly after attending a Dharma talk for the first time in my life, given by Gonsar Tulku Rinpoche, who spoke with great devotion about his master, Geshe Rabten! Thank you for this article!

Thanks Rinpoche. I shall read and study this over and over again. May we all have the merits to practice this perfection along the path.

Thank you, Rinpoche, for sharing (in this post), “The Perfection of Concentration” teaching of Geshe Rabten Rinpoche and a biography of Geshe Rabten himself.

I find the teaching on The Perfection of Concentration very powerful and precious. I now understand more clearly why this unruly mind of mine requires tremendous effort to tame with mindfulness and concentration.

Rabten Geshe Rinpoche himself has indeed attained the Perfection of Concentration and Wisdom(in tandem) among all his other attainments. This has manifested in his achieving such clear and precise style of logical debate as to result in his being compared to the great Dharmakirti,the great Buddhist logical thinker. He was also chosen to be the Philosophical Assistant of the Dalai Lama in 1964, a mark of recognition of his great mental prowess and wisdom.

Furthermore, he was a great teacher of Dharma for his ability to bring the “essence of the thoughts of Buddha close to the listeners”.People who listened to his teachings felt “all the unclearness disappear” and a “calmness and clearness” would take its place and spread in the mind. This is further indication of how he has used his mastery of clarity, focus and calmness of mind to benefit all beings through the teaching and spread of Dharma.

I prostrate in body, speech and mind to the great and humble Master of our time, Geshe Rabten Rinpoche.

Love this!!!!!!!

Dear Rinpoche,

I think I kinda understand the agitation with your examples, but I don’t quite get the part on torpor and how to apply the attentive application..

How do we differentiate torpor from the actual concentration? Can you give some examples on how to apply attentive applications?

Thank you Rinpoche.

Lew

Dear Rinpoche,

Thank you for sharing this article. I love it. It explains the meditation process in such a simple, easy to understand form.

Plus, I now know the meaning behind this beautiful painting.

Wishing you a beautiful day.

Dee Dee

Dear Dee Dee, it takes a special intelligence coupled with merit to appreciate what is taught on this article. I am most glad to see you have interest in it. It shows you are very deep. If you pursue the study, practice and application of Dharma, I know you will have results. Focus and determination are all that is needed. I hope you will grab this opportunity and go all the way. I am here and my purpose is to bring this to you and others who are ready…I wish you so much luck.

TR