Zanabazar: The First High Saint of Mongolia

(By Tsem Rinpoche)

Zanabazar (1635-1723) was the first high saint (Ondor Gegeen) of Mongolia. Although he was born to an aristocratic Khalkha Mongol family, Zanabazar is remembered today not for his privileged background, but for using his immense talent and charisma to propagate Buddhism and benefit his fellow countrymen.

Widely regarded as the “Michelangelo of Asia”, Zanabazar was a renowned painter, sculptor, architect and costume designer. His artistic skills were matched by his literary prowess as a Buddhist scholar, linguist and poet. Historians say that he single-handedly ushered Mongolia into a period of cultural renaissance. In addition to these talents, Zanabazar was a charismatic leader and an astute politician. Zanabazar’s use of his artworks as a tool of diplomacy was crucial to the survival of the Khalkha Mongols and the influence they wielded. Today, almost three centuries after his death, Zanabazar continues to inspire many to achieve their personal best and to be a beacon of light and hope.

Political Background

We have to understand the political circumstances into which Zanabazar was born, to fully appreciate his life, influence and the significance of his deeds. In 1578, approximately six decades before Zanabazar was born, Altan Khan (1507–1582), an ambitious Mongolian military leader forged a mutually beneficial relationship with Sonam Gyatso (1543-1588), a Tibetan Buddhist spiritual leader of the Yellow Hat (Gelug) tradition. Sonam Gyatso recognised Altan Khan as the reincarnation of Genghis Khan. In return, Altan Khan recognised Sonam Gyatso as the reincarnation of an influential 13th-century lama, Lama Drogon Chogyal Phagpa. He bestowed upon him the title of Dalai Lama (“Ocean Lama”) and Ochirdara (“Vajradhara”). The Dalai Lama title was posthumously conferred upon the two incarnations who preceded Sonam Gyatso as well.

This understanding between Altan Khan and Sonam Gyatso set an important precedent; the role of spiritual recognition in legitimising the power of Mongolian aristocracy. For the next century, the Mongol ruling class continued to seek the blessings of Tibetan spiritual leaders to affirm their authority. In return, these spiritual leaders were allowed to spread Buddhist doctrine and build temples (datsan in Mongolian) across the country.

However, by the 17th century, Mongolian power was in decline. In 1632, Emperor Hong Taiji (皇太極) (r. 1626 – 1643), the first emperor of the Qing Dynasty, launched a campaign against the unpopular Ligdan Khan (r. 1603–1634). Ligdan Khan fled to Kokenuur where he died of smallpox two years later. His son, Ejei Khan, was handed over to the Qing Dynasty, and this marked the beginning of the Qing Dynasty rule over Inner Mongolia.

Early Life

The birth place of Zanabazar

Zanabazar was born in 1635 to a prominent Khalkha Mongolian aristocratic family in present-day Yesönzüil, a province in Southern Mongolia. He was the second son of Tusheet Khan Gombodorj (1594-1655) and Khandojamtso. Zanabazar was given the birth name Eshidorji. His family’s ancestry could be traced back to the great Genghis Khan, and Zanabazar was the grandson of Altan Khan’s nephew, Abtai Sain Khan (1554–1588).

Just like his uncle, Abtai Sain Khan had been a great patron of the Gelug school and propagated this tradition among the Khalkha Mongols. Even as a child, Zanabazar displayed extraordinary intelligence and devotion. He was able to recite the Praise of Manjushri (Jambaltsanjod) perfectly when he was just three years old. Zanabazar also excelled in Tibetan and Indian scriptures, as well as in other fields as diverse as medicine, literature, philosophy, art and architecture. By 1640, Zanabazar’s extraordinary qualities had become widely known. The assembly of Khalkha nobles decided to acknowledge Zanabazar as a high saint (Ondor Gegeen) or “Holy Enlightened One” (Bogd Gegeen) and the Khalkha supreme religious leader. The members of the Khalkha aristocracy pledged their allegiance to him in Tsagaan Nuur.

Tsagaan Nuur, the place where Zanabazar was enthroned as Ondor Gegeen

After the acknowledgement, Zanabazar was selected to preside over the monastery near Tsagaan-nuur, in present-day Khovsgol Province. The recognition of Genghis Khan’s descendant as a living Buddha (khutagt) carried political significance. It strengthened the prestige of the Khalkha nobility and accorded them religious legitimacy.

In 1647, Zanabazar‘s relatives took him to Beijing to pay homage to the newly crowned Emperor Shunzhi (順治帝). Zanabazar became the first patriarch, the highest-ranking lama after the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama, to be recognised by the Qing Dynasty. In the same year, aged just 12, Zanabazar established his own monastery in a travelling ger camp. This monastery was initially known as Baruun Khuree or Monastery of the West and later renamed Shankh Monastery. In 1787, this monastery was located in Ovorkhangai Province, Mongolia.

Baruun Khuree Monastery in Ovorkhangai Province, Mongolia

Zanabazar’s school dress (left) and the child dress that he was using at Baruun Khuree Monastery (right)

Recognition in Tibet

In 1649, Zanabazar entered Tibet’s famed Drepung Monastery.

Mongolia and Tibet enjoyed a close religious and political relationship and many Mongolian monks studied in Tibet. In 1649, Zanabazar entered Tibet’s famed Drepung Monastery, where he studied the profound sutric and tantric traditions under the guidance of the two highest Gelug lamas, the 4th Panchen Lama, Lobsang Chokyi Gyeltsen (1570-1662) and his disciple, the 5th Dalai Lama, Lobsang Gyatso (1617-1682). In Tibet, Zanabazar also studied various artistic techniques, including bronze casting.

The 5th Dalai Lama recognised Zanabazar as the reincarnate leader of the Jonang school, Taranatha (1575-1634), who entered clear light one year before Zanabazar’s birth. This lineage of incarnation could be traced back to Khutuktu Jetsundampa, one of Buddha Shakyamuni’s original disciples. Zanabazar was his 16th reincarnation. Taranatha was a legendary scholar and, as his reincarnation, Zanabazar was given the Sanskrit name of Jnana-Vajra, which means Wisdom Vajra. This name later became Zanabazar.

It was politically significant that Zanabazar accepted the Dalai Lama’s recognition of his incarnation line. It meant that Zanabazar accepted the authority of the Dalai Lama and the supremacy of the Gelug sect. After several years of study, the Dalai Lama advised him to return to Mongolia to propagate Buddhism.

About Taranatha

Taranatha (1575–1634) was a great scholar of the Jonangpa school of Tibetan Buddhism and a prolific writer. He was closely associated with the practice of Kalachakra Tantra and Tara. Taranatha studied under the guidance of many great masters that included the Indian teacher, Buddhaguptanatha as well as Je Draktopa, Kunga Tashi, Yeshe Wangpo and Jampa Lhundrup.

Among Taranatha’s important literary works are “History of Buddhism in India”, “The Golden Rosary”, “The Origins of the Tantra of the Bodhisattva Tara”, “Twenty-One Profound Meanings” and “Commentary on the Heart Sutra”. Several of these precious writings have survived the test of time and are available to modern readers in several languages, including English. In 1614, Taranatha went to Mongolia to propagate Buddhism and established several monasteries there.

Zanabazar: The God King of Mongolia

Rise to Power

In 1651, Zanabazar returned to Outer Mongolia, accompanied by 600 artists, craftsmen and monks. It was a testament to his remarkable charisma that, at the age of sixteen, he was able to inspire so many people to leave behind everything they knew to follow him.

Upon his return, Zanabazar assumed his place as the spiritual and political leader of the Khalkha Mongols. Besides the construction of many monasteries and temples, he introduced innovations in religious rituals, socialised the prayer texts that he composed and modified the chanting melodies. He designed new robes for the Mongolian monastics and sent monks to the three great Gelug monasteries (i.e., Sera, Gaden, Drepung) and Tashi Lhunpo for advanced studies. Zanabazar himself was known to have made another visit to Tibet in 1656.

Tovkhon Monastery

In 1653, he built Happy Secluded Place (Bayasgalant Aglag Oron) Monastery on the Shireet Ulaan Uul Mountain. The name of this monastery would later be changed to Tovkhon Monastery. Zanabazar produced many of his most famous works of art there. Among the other monasteries he built were Ikh Khuree on Khentii Mountain (1654), Saridgiin Monastery on Khentii Mountain (1680) where the remains of Taranatha were enshrined and Zuun Khuree (1702).

In addition to these permanent structures, Zanabazar built several mobile temples to adapt to the nomadic lifestyle of his followers. These temples contained religious sculptures, paintings and wall ornaments designed in beautiful Nepalese-Tibetan style. Some of the works were created by Zanabazar and his students while others had been brought from Tibet.

Zanabazar, an astute political and spiritual leader, accepted Qing’s sovereignty over Mongolia. By the late 1650s, he had managed to consolidate his authority over the Khalkha tribal leaders. In 1658, Zanabazar led the assembly of nobles at Erdene Zuu Monastery, which had been established by his grandfather, Abtai Sain Khan. In 1659, he conferred titles to Mongolian aristocrats at Olziit Tsagaan Nuur. Zanabazar utilised the gers offered by the Khalkha nobility during his recognition in 1639 as his mobile palatial residence (Orgoo). The mobile palace became known as Yellow Screen Palace (Shira Busiin Ord). In 1778, Zanabazar settled it near the Selbe and Tuul rivers at the foot of Bogd Khan Mountain. This location would later become known as Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia.

Erdene Zuu Monastery

Zanabazar’s Yellow Screen Palace

Zanabazar established several departments to manage the monasteries and temples including:

- Department of Treasury

- Department of Administration

- Department of Meals

- Department of the Honoured Doctor

Artistic Endeavours

Zanabazar is regarded as an artist extraordinaire and the face of the Mongolian Renaissance. His fame spread to other Buddhist countries during his lifetime and travelled even further in the centuries since. In addition to his skills in medicine, language and astronomy, he was a talented painter, musician and bronze and copper caster. Together with his students and craftsmen, Zanabazar produced many bronze Buddha statues and Buddhist paintings (thangkas).

Zanabazar admired the Nepalese artistic style which was prevalent in the Gelug School at the time. His admiration is apparent in the artwork that he produced. In the 1670s and 1680s, Zanabazar and his apprentices produced hundreds of Buddhist-inspired artworks at Tovkhon Monastery. He wanted to fill the monasteries and temples with these inspiring pieces and connect the spirit of Buddhism to the masses beyond the confines of the nobility and the monastic community.

The statues were made in the style known today as the “Zanabazar School”, which uses a hollow yet seamless brass casting technique. Zanabazar discovered the sculpting technique known as lost-wax casting that allowed him to make brass statues without the need for welding. The statues are usually depicted in deep meditation, guided by the desire to liberate sentient beings from their delusions. Zanabazar’s female Buddhas are infused with feminine beauty. They are typically depicted with arched eyebrows, small but fleshy lips, high nose and forehead. Among his greatest surviving works are the statues of Green Tara, White Tara, Standing Maitreya, Twenty-One Taras, the Five Dhyani Buddhas, Vajrasattva, Sitasamvara and Vajradhara.

Nicholas Roerich, a renowned Russian painter, archaeologist and writer of the 19th century wrote that Zanabazar’s work represents “the nomads’ aesthetic views on art, their worldview and mentality.” [mfa.gov.mn]

Zanabazar continued to produce these beautiful statues and other artworks at Tovkhon Monastery until 1688, when the Dzungar Oirat Mongols destroyed the premises in their war with the Khalkha Mongols.

Writing Scripts

Soyombo Script

In 1686, Zanabazar designed a writing script known as the Soyombo Script. It was based on the Lantsa script from India. Soyombo was also known as “Svayambhu”, which means “self-sprung”. In the same year, Zanabazar commenced his project to translate the Kangyur, the spoken words of the Buddha into Mongolian. He also printed many Mahayana Sutras and the texts that he had composed.

Today, Soyombo Script can still be found in inscriptions in Mongolian temples and historical texts. Since 1921, Soyombo symbols have been featured on Mongolia’s national emblem and can be found on its currency, stamps and the national flag.

Horizontal Square Script

In addition to the Soyombo Script, Zanabazar designed the Horizontal Square Script (Xawtaa Dorboljin) for writing Sanskrit, Tibetan and Mongolian. The script has similarities with the Tibetan script and the Phags-pa script, which was created by Drogon Chogyal Phagpa, a 13th-century Mongolian lama. This script is less common and mainly used in calligraphy manuals. Presently, the Horizontal Square Script and Soyombo Script could be found in Buddhist inscription known among the limited group of learned Buddhist scholars in Mongolia.

Selected Readings (Free Download)

The texts above were sourced from legitimate book-hosting services offering these texts for free download. They are made available here for purely educational, non-commercial purposes.

Art as a Tool of Diplomacy

As a farsighted politician and an astute diplomat, Zanabazar used his artworks to win protection, appease enemies and forge bilateral relationships with considerable success. When conflict threatened the peace between the Khalkha and the Dzungar Mongols, Zanabazar used his sacred text and artwork to earn the trust of Galdan Boshugtu Khan (1644-1697), the Dzungar leader. Like Zanabazar, Galdan had studied Buddhism in Tibet under the guidance of the 4th Panchen Lama and the 5th Dalai Lama. In 1686, Zanabazar attended a peace conference initiated by the Qing Emperor Kangxi (康熙) (1654-1722) to forge reconciliation between the Khalkhas and the Dzungars. The 5th Dalai Lama also advocated peace and advised Galdan Boshugtu Khan to maintain the spirit of non-aggression in the region.

Unfortunately, the fragile peace between the Khalkhas and the Dzungars collapsed when the forces of Khalkha Tusheet Khan killed Galdan Boshugtu Khan’s brother in 1687. The hideous conflict culminated in an all-out war between the Khalkhas and the Dzungars that led to the destruction of Zanabazar’s beloved Tovkhon Monastery and several other important places of worship. In 1688, Zanabazar and 20,000 Khalkha refugees had to escape to Inner Mongolia and seek the protection of Emperor Kangxi.

Zanabazar gave his beautiful artwork to Emperor Kangxi and offered to make Khalkha Mongols lands a protectorate of the Qing Empire. His sincerity, wisdom and knowledge of Buddhism earned the trust, respect and admiration of Emperor Kangxi.

The Battle of Jao Modo

Background

In 1691, Zanabazar convinced three Khalkha rulers to submit themselves to Qing authority (click to enlarge)

Emperor Kangxi knew that if the Dzungars prevailed over the Khalkha, they would pose a threat to the relatively young Qing Empire. No Qing ruler wanted a unified Mongolia; tales of the devastation wreaked by the 13th century Mongol conquests weighed heavily on their minds. Emperor Kangxi agreed to send his army to help subdue Galdan Boshugtu Khan’s forces. In 1690, the Qing managed to lure the Dzungars to an area 350 km (217.4 mi) north of Beijing with the promise of peace negotiations. Here, the Khalkhas with the support of the Qing army ambushed them in what we know today as the Battle of Ulan Butung.

The Battle of Ulan Butung

The outraged Galdan Khan and his remaining forces managed to escape to the upper part of the Kherlen River where they camped for the next six years. During this period, Zanabazar spent his time in China as the spiritual mentor of Emperor Kangxi, who bestowed upon him the title of “Da Lama” (Great Lama). Zanabazar divided his time between Beijing in the winter and Jehol in the summer. In 1691, Zanabazar convinced three Khalkha rulers to submit themselves to Qing authority. With their troops added to the emperor’s army, the force was so large that they required 1,333 carts just to carry food provisions. Emperor Kangxi began to prepare for a decisive battle against the Dzungars.

The Battle

In March 1696, Emperor Kangxi led 80,000 troops and 235 cannons across the Gobi Desert. His General-In-Chief, Fiyanggu led an army of 30,000 troops with another 10,000 on standby to trap Galdan Khan. At first, Galdan Khan outsmarted them and escaped from his camp at the Kherlen River. On June 12, 1696, 5,000 of Galdan Khan’s soldiers were sent to fight the Fiyanggu army. Unfortunately, this manoeuvre sent them to the heart of the Qing army and forced them to fight for their lives. The Qing army gained their first victory and seized the surrounding hills, which then served as strategic locations from where they could attack the Dzungars.

They fired their cannons and used wooden barricades as shields from counter attacks. Perhaps because he had predicted his own doom, Galdan Khan instructed his troops to attack the heart of the Qing army. The suicidal strategy seemed to work and the centre of the Qing army was in disarray. However, another detachment attacked the Dzungars from behind to capture their provisions, and the Dzungar troops started to flee. Galdan Khan’s warrior queen, Anu, led a counterattack to enable her husband to escape. She was successful but died in the process. Galdan Khan escaped to the Altai Mountain with his few remaining troops and died of illness on April 4, 1697.

Aftermath

After their defeat at the Battle of Jao Modo, the Dzungars were pushed to the westernmost part of the Qing Empire until their ultimate defeat in 1758 at the battle of Oroi-Jalatu and Khurungun.

The Spiritual Mentor to the Qing Emperor

Zanabazar stayed in China for several years after the battle of Jao Modo. He was a respected member of the Qing Court, renowned for his wisdom. Emperor Kangxi and many in the court became devout Buddhists. His contributions to the Qing Court allowed the Mongols to preserve their unique identity, lifestyle and political borders. In 1698, Emperor Kangxi invited Zanabazar to go with him on a pilgrimage to Mount Wutai, the earthly abode of Manjushri, the Buddha of Wisdom. In 1699, Zanabazar visited Khalkha Mongolia briefly to attend the funeral of his elder brother, Tusheet Khan Chankhuundorj. Even after Zanabazar returned home permanently in 1701, he made annual journeys to Beijing to visit the emperor.

Later Life and Death

Erdene Zuu Monastery

Upon his return to Khalkha Mongolia in 1701, the 66-year-old Zanabazar started to work on the restoration of Erdene Zuu Monastery. It had been severely damaged by Galdan Khan’s troops in 1688. He also oversaw the construction of various other Buddhist monasteries and places of worship.

On December 20, 1722, Zanabazar’s patron and student, Emperor Kangxi passed away. Despite his advanced age, Zanabazar travelled to China to preside over the funeral rites at Yellow Monastery (Huang Si, 黃寺) in Beijing. On February 18, 1723, less than two months after Emperor Kangxi’s demise, Zanabazar entered clear light at 88 years of age. There were rumours that the new emperor, Yongzheng (雍正) poisoned him. However, this allegation has never been proven. He was embalmed and his body was returned to Urga, the present-day Ulaanbaatar.

Zanabazar’s tomb temple

After the demise of Zanabazar, his brother’s great-grandson was recognised as his incarnation. He was enthroned with the support of the Qing court and the Yellow Hat clergy in Lhasa, Tibet.

To enshrine Zanabazar’s remains, Emperor Yongzheng had a monastery built at the spot where his mobile residence was encamped at the time of his passing. Constructed at a cost of 100,000 liang silver (approx. USD 2.2 million in today’s money), its architecture resembled that of the emperor’s own palace. It was dedicated to Zanabazar’s main deity, Maitreya.

Amarbayasgalant Monastery

This monastery would later become known as the Amarbayasgalant Monastery. It was completed in 1736, one year after Emperor Yongzheng’s death. Zanabazar’s remains were finally laid to rest in a stupa at Amarbayasgalant Monastery in 1779. It was partly destroyed during the Stalinist purges of 1937 and the remains of the great Zanabazar were removed and cremated in the nearby hills. Today, only 28 of the 40 original buildings of the complex remain. UNESCO has been funding a restoration project at this historic site since the late 1980s.

Amarbayasgalant Monastery complex

Amarbayasgalant Monastery

How Zanabazar’s Contribution is Viewed Today

Today, Zanabazar is considered a larger than life historical figure. Not only is he celebrated for his role in propagating Buddhism in Mongolia, but also for ushering the Mongols into a period of cultural renaissance and establishing their unique cultural identity.

Even during Mongolia’s socialist era from 1921 to 1991, Zanabazar was acknowledged for his artistic achievements, cultural contribution and as a great scholar. However, Socialists regarded Zanabazar as a traitor for capitulating to Qing sovereignty and for his role in having three Khalkha rulers follow suit in 1691. In today’s post-socialist era, however, Zanabazar has been absolved from that treasonous image. It is generally agreed today that he was acting for the long-term interest of Mongolia by allying himself with the Qing Empire.

Zanabazar’s shirt

Today, a Mongolian artist painter and a Buddhist teacher, Gankhuugiin Purevbat, is working with his disciples to revive the Mongolian Renaissance that was started by Zanabazar almost three centuries ago.

With the help of his disciples, Purevbat rebuilt the Zanabazar Mongolian Institute of Buddhist Art, which was a part of Gandantegchinlen Monastery. The Communists destroyed the monastery in 1937. With this institute, Purevbat promotes the education of artists and art teachers and regularly organises exhibitions on various art forms such as dance, painting, and sculptures.

Purevbat’s Dream: The Renaissance of Buddhist Art in Mongolia

The Portraits of Zanabazar

As he was one of the greatest Buddhist masters of his time, Zanabazar’s images have been treated as objects of devotion. They have been crafted using materials ranging from wood, bronze and smaller moulds. This suggests that these images were mass-produced and in high demand. Many of them still survive today. The two more common ones are:

Zanabazar Holding Vajra and Bell

In this image, Zanabazar is depicted holding two implements that he inherited from Taranatha, his previous incarnation. His right-hand holds a vajra at his chest, and his left-hand holds a ritual bell at his stomach. It is also said that the vajra and bell represent wisdom and compassion, the two essential qualities that will lead practitioners to enlightenment. Zanabazar’s head was round, which is attributed to the comment that Emperor Kangxi’s mother made when she first saw him, “This Blessed One of yours is a beautiful lama, like [a] full moon.” [asianart.com]

Zanabazar Cutting Meat

It is generally accepted that the image of Zanabazar holding the vajra and bell is for religious practitioners. For other Mongolians, Zanabazar wanted an image depicting him cutting a cooked sheep with a sharp knife. The meat represents abundant wealth, and the sharp knife represents the Mongolian people’s intelligence. In this painting, Zanabazar is depicted in a Mongolian attire.

According to Aleksei Pozdneyev, a 19th-century Russian who specialised in Mongolian studies, the 4th Bogd Gegeen instructed that the reliquary stupa that housed Zanabazar’s mummified body be opened in 1798. This was to allow a talented artist to paint a realistic portrait of Zanabazar.

The Fine Arts Zanabazar Museum

The Fine Arts Zanabazar Museum

In 1966, the Fine Arts Zanabazar Museum was established in the Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar. The museum displays paintings, carvings and sculptures by Zanabazar, including the five Dhyani Buddhas. It also contains works by other artists from the 17th to the 20th century, Buddhist ritual items such as the tsam mask and many precious artefacts.

Since 2004, the Zanabazar Museum of Fine Art has been part of the UNESCO Programme for the Preservation of Endangered Movable Cultural Properties and Museum Development.

Zanabazar Museum Ulaanbaatar

Or view the video on the server at:

https://video.tsemtulku.com/videos/ZanabazarMuseumUlaanbaatar.mp4

Other Legacies

Today, almost three centuries after his death, Mongols continued to revere Zanabazar and promote his legacy:

- In 1970, the Zanabazar Buddhist University was established in Ulaanbaatar

- A street in the centre of the Mongolian capital is named Ondor Gegeen Zanabazar after him (Өндөр Гэгээн Занабазарын гудамж)

- In 2009, a genus of dinosaur was named after Zanabazar.

A genus dinosaur named after Zanabazar

Selected Artworks Related to Zanabazar

Standing Manjushri (left), Standing Maitreya (middle), and Sitting Maitreya (right) by Zanabazar (click to enlarge)

Sources:

- “Zanabazar”, Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, 15 August 2018, [website], https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zanabazar (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Taranatha”, Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, 18 October 2018, [website], https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taranatha (accessed 18 October 2018).

- “Battle of Jao Modo”, Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, 16 September 2018, [website], https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Jao_Modo (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Galdan Boshugtu Khan”, Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, 16 September 2018, [website], https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galdan_Boshugtu_Khan (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Queen Anu”, Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, 25 October 2017, [website], https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen_Anu (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Mongolian Exhibition”, Asian Arts, [website], http://asianart.com/mongolia/zanabazr.html (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “MONGOLIAN LEGENDARY PERSONS: ZANABAZAR (1635-1723)”, Legend Tour, [website], https://www.legendtour.ru/eng/mongolia/history/zanabazar.shtml (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Fine Arts Museum, Ulaanbaatar: Zanabazar and his school”, University of Washington, [website], https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/museums/ubart/zanabazar.html (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “The rise of Genghis Khan”, ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA, [website], https://www.britannica.com/place/Mongolia/The-rise-of-Genghis-Khan#ref1111706 (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts”, Lonely Planet, [website], https://www.lonelyplanet.com/mongolia/ulaanbaatar/attractions/zanabazar-museum-of-fine-arts/a/poi-sig/434876/357066 (accessed 10 October 2018).

- Watt, Jeff, “Teacher: Yeshe Dorje (Zanabazar) Cutting Meat”, Himalayan Art Resources, December 2015, [website], https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=4230 (accessed 10 October 2018).

- Croner, Don, “Guide to Locales Connected With The Life of Zanabazar: First Bogd Gegeen Of Mongolia”, BookSurge Publishing, March 2, 2006.

- Tsultemin, Uranchimeg, “Zanabazar (1635–1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia”, Oxford Scholarship Online, [website], http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199958641.001.0001/acprof-9780199958641-chapter-7 (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “The Fine Arts Zanabazar Museum, Mongolia”, ASEMUS: Asia – Europe Museum Network, [website], http://asemus.museum/museum/fine-arts-zanabazar-museum-mongolia/ (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “The Fine Arts Zanabazar Museum”, Google Arts & Culture, [website], https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/the-fine-arts-zanabazar-museum (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “BabelStone Zanabazar”, BabelStone Fonts, [website], http://www.babelstone.co.uk/Fonts/Zanabazar.html (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Zanabazar Square”, ScriptSource, [website], http://scriptsource.org/cms/scripts/page.php?item_id=script_detail&key=Zanb (accessed 10 October 2018).

- Aldrich, M.A., “The Dalai Lama in Mongolia: ‘Tournament of Shadows’ Reborn”, The Diplomat, 3 December 2016, https://thediplomat.com/2016/12/the-dalai-lama-in-mongolia-tournament-of-shadows-reborn/ (accessed 10 October 2018).

- Khash-Erdene, B., “Zanabazar – the Michelangelo of Asia” UB Post, 20 August 2012, http://ubpost.mongolnews.mn/?p=619 (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Undur Gegeen Zanabazar”, Buddhist tour Mongolia, 9 May 2016, [website], https://www.buddhisttourmongolia.com/buddhism-in-mongolia/undur-gegeen-zanabazar/ (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “G.ZANABAZAR, HIGH PRIEST AND ARTIST”, Angelfire, [website], http://www.angelfire.com/mn2/zanabazar/english/biogriphy.htm (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “1st Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, Zanabazar”, chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com, [website], http://www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com/en/index.php?title=1st_Jebtsundamba_Khutuktu,_Zanabazar (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Beginning of Spread of the Yellow Sect of Buddhism in Mongolia”, Mongols.eu, [website], http://www.mongols.eu/mongolia/history-buddhism-mongolia/history-of-the-yellow-sect-of-buddhims-in-mongolia/ (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “Undur Gegeen G. Zanabazar”, Google Arts & Culture, [website], https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/undur-gegeen-g-zanabazar/_QHVVsjza7D_vA (accessed 10 October 2018).

- “A Mongolian tsatsa with a portrait of Ondor Gegeen Zanabazar (1635-1723), in a ga´u. 19th century”, lempertz.com, [website], https://www.lempertz.com/ru/catalogues/lot/1112-1/38-a-mongolian-tsatsa-with-a-portrait-of-oendoer-gegeen-zanabazar-1635-1723-in-a-gau-19th-cent.html (accessed 10 October 2018).

For more interesting information:

- Buddhism in the Mongol Empire

- 10,000 Mongolians Receive Dorje Shugden

- Zaya Pandita Luvsanperenlei (1642 – 1708)

- Emperor Kangxi | 康熙皇帝

- Emperor Kangxi and Wu Tai Shan

- The Imperial Tomb of Emperor Kangxi

- Kalmyk People’s Origin – VERY INTERESTING

- Danzan Ravjaa: The Controversial Mongolian Monk

- Agvan Dorjiev: The Diplomat Monk

- Mongolian Astrology and Divination

- The Fifth Dalai Lama and his Reunification of Tibet

- Tsem Rinpoche’s Torghut Ancestry

- My recollection of H.E. Guru Deva Rinpoche

- The Ethnics Groups of China

- Archaeologists Unearth Tomb Of Genghis Khan

- Incredible Geshe Wangyal

- Tsem Rinpoche’s heritage in China

- Auspicious Mongolian Omen

- Namkar Barzin

Please support us so that we can continue to bring you more Dharma:

If you are in the United States, please note that your offerings and contributions are tax deductible. ~ the tsemrinpoche.com blog team

Awesome life’s story and legacy of Ondor Gegeen Zanabazar the first Jebtsundamba Khutuktu of the Gelugpa lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia and his profound impact on Mongolian Buddhism. Zanabazar a man of all trades was a prodigious sculptor, painter, architect, poet, costume designer, scholar and linguist .He was a descendant of Chingis Khan, born into a prominent Oirot Mongol family. Considered to be a living reincarnation of one of the important earlier Buddhist leaders in Mongolia. Zanabazar showed signs of advanced intelligence, linguistic abilities, and religious devotion from an early age. He is much revered for his contributions to Buddhist learning and for his reforms of Mongolian Buddhism. He was best known for his intricate and elegant Buddhist sculptures. Viewed as one of Mongolia’s most prominent historical figures, celebrated for propagating Tibetan Buddhism throughout Mongolia to this day.

Thank you Rinpoche for this sharing of the first high saint of Mongolia.

Zanabazar was the sixteenth Jebtsundamba Khutuktu and the first supreme spiritual authority, of the Gelugpa lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia. Zanabazar was a talented scholar and an influential leader. A descendant of Ghingis Khan, he is best known for his intricate and elegant Buddhist sculptures created in the Nepali-derived style. The two most famous being the White Tara and Varajradhara, sculpted in the 1680s. Mongolia as the northern center of Buddhist culture, he promoted peace and enlightenment in an era of extreme political instability in Central Asia. Zanabazar revolutionized the outdated beliefs and ideologies of 17th-century Mongolian nomadic culture. For over two centuries after his death, Zanabazar’s work continued to inspire artists to create in the likeness of his masterpieces. His legacy lives on through the artists of the School of Zanabazar to this day. Interesting read.

Thank you Rinpoche for sharing this inspiring

Interesting biography of a great Lama Zanabazar was a renowned painter, sculptor, architect and costume designer. He was known as“Michelangelo of Asia”, for his artistic skills which were matched by his literary prowess as a Buddhist scholar, linguist and poet. Zanabazar as a historical figure played an important role in propagating Buddhism in Mongolia. He had established Mongolian unique cultural identity. Zanabazar was the first Bogd Gegeen or high-saint-of-mongolia or supreme spiritual authority, the Gelugpa lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Outer Mongolia. He is believed to be a Geluk protagonist whose alliance with the Dalai and Panchen Lamas was crucial to the dissemination of Buddhism in Khalkha Mongolia. Interesting read with all the rare pictures shared.

Thank you Rinpoche for this sharing.

Thank you so much for this article. This article is mainly about Zanabazar, the first high saint of Mongolia. After reading this article, i get to know that Zanabazar was a renowned painter, sculptor, architect and costume designer where his artistic skills matched by his literary prowess as a Buddhist scholar, linguist and poet.

This understanding between Altan Khan and Sonam Gyatso is an important precedent and the role of spiritual recognition in legitimizing the power of Mongolian aristocracy. Thank you.

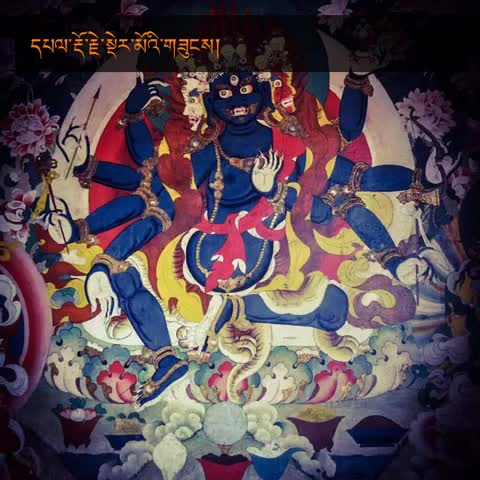

The great Protector Manjushri Dorje Shugden depicted in the beautiful Mongolian style. I hope many Mongolians will print out this image and place in their houses to create an affinity with Dorje Shugden for greater blessings. To download a high resolution file: https://bit.ly/2Nt3FHz

The powerful Mongolian nation has a long history and connection with Manjushri Dorje Shugden, as expressed in the life of Venerable Choijin Lama, a State Oracle of Mongolia who took trance of Dorje Shugden among other Dharma Protectors. Read more about Choijin Lama: https://bit.ly/2GCyOUZ

The Tara made by Zanabazar are truly amazing, and beautiful. When statues are made so beautifully, it acts an inspiration for practitioners.

以下是扎纳巴扎尔的一些中文简介,希望给大家对扎纳巴扎尔有个基本的印象:

扎纳巴扎尔(Zanabazar)是第一世哲布尊丹巴呼图克图。哲布尊丹巴呼图克图是外蒙古藏传佛教最大的活佛世系,属格鲁派,于17世纪初形成,与内蒙古的章嘉呼图克图并列为蒙古两大活佛。是与达赖喇嘛、班禅额尔德尼、章嘉呼图克图齐名的藏传佛教的四大活佛之一。

然而扎纳巴扎尔最广为人知的,却是他在佛教艺术上的贡献。他所创造的佛像深具个人特色,继而开创了蒙古佛教艺术的新纪元。他也因此被称为“亚洲的米开朗基罗”。扎那巴扎尔的佛教造像整体浇铸,再用金属钉组装固定在一起,人物比例精准、造型优美、面部清秀俊朗、气质典雅。他的白度母造像更被誉为史上最美的《白度母坐像》。

扎纳巴扎尔的其他著名创作包括绿度母、弥勒佛、五方佛等。目前他的大部分作品都被收藏在蒙古的扎纳巴扎尔博物馆内。

I really enjoyed reading this article about Zanabazar, may the dharma reach its golden age once more under the auspices of the high lamas there. Zanabazar was also a very farsighted leader, and led his people to less bloodshed than if he had led using the sword. he used his wisdom and intelligence to help his people during a period of strife amongst Mongolians. The Khalka Mongols then were sandwiched between the newly formed Qing Empire and the Dzungzar Mongol a potent force in itself. Also the statues Zanabazar made were of the finest qualities and one feels very inspired just looking at them.

Zanabazar was born to a prominent Khalkha Mongolian aristocratic family in present-day Yesönzüil, a province in Southern Mongolia. He was the second son of Tusheet Khan Gombodorj and Khandojamtso. Zanabazar was given the birth name Eshidorji. Widely regarded as the “Michelangelo of Asia”, Zanabazar was a renowned painter, sculptor, architect and costume designer.His artistic skills were matched by his literary prowess as a Buddhist scholar, linguist and poet.The 5th Dalai Lama recognised Zanabazar as the reincarnate leader of the Jonang school, Taranatha, who entered clear light one year before Zanabazar’s birth.

Zanabazar returned to Outer Mongolia, accompanied by 600 artists, craftsmen and monks. It was a testament to his remarkable charisma that, at the age of sixteen, he was able to inspire so many people to leave behind everything they knew to follow him.Zanabazar built several mobile temples to adapt to the nomadic lifestyle of his followers. These temples contained religious sculptures, paintings and wall ornaments designed in beautiful Nepalese-Tibetan style. Some of the works were created by Zanabazar and his students while others had been brought from Tibet.Zanabazar is regarded as an artist extraordinaire and the face of the Mongolian Renaissance.

His fame spread to other Buddhist countries during his lifetime and travelled even further in the centuries since. In addition to his skills in medicine, language and astronomy, he was a talented painter, musician and bronze and copper caster. Today, Zanabazar is considered a larger than life historical figure. Not only is he celebrated for his role in propagating Buddhism in Mongolia, but also for ushering the Mongols into a period of cultural renaissance and establishing their unique cultural identity. Thank you Rinpoche and blog team for this great and inspiring write up!????