Vows: The Roots of All Attainments

“To take vows is to consciously eliminate the stimuli that would further reinforce negative habits and also to cut them. Vows is the key.” — His Eminence the 25th Tsem Rinpoche

(By Tsem Rinpoche and Pastor Adeline)

Dear friends,

It is with great humility that I have been given the opportunity to present to you this research on vows on His Eminence the 25th Tsem Rinpoche’s sacred space.

In Buddhism, the practice of upholding vows is one of the Three Principle forms of Buddhist training that all Buddhists engage in along with the other two trainings – meditation and wisdom. The root of all attainments is to keep vows and commitments intact regardless of obstacles and difficulties faced. In other words, keeping vows will guarantee a stream of spiritual attainments. According to the 15th day of teachings in Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, H.H. Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche said:

“…it is more beneficial in these degenerate times to uphold one’s ethics than to make offerings constantly, throughout the day and night, to the Buddhas of the three times. It is more beneficial to keep the ethics of our Teacher Sakyamuni’s doctrine for a day in this human world of sorrows than to keep our ethics for eons in Buddha Ishvaraja’s pure land of northeast quarter. They say it is more beneficial to keep just one form of ethics now than to have completely kept the basic trainings during the earlier parts of this eon; this is a greater act than making offerings to many Buddhas for tens of millions of eons.”

Therefore, to be able to hold vows in these degenerate times is very meritorious, thereby allowing us to expedite our practice if the vows and commitments are kept well. It is with this belief that I sincerely wish that the content below will provide a better understanding for everyone regarding the function of vows and their benefits.

I would like to take this opportunity to extend my sincere appreciation to Pastor David and Pastor Jean Ai for their time, valuable advice, as well as editing of this article.

Lastly, I am greatly indebted to my Guru, the precious and rare jewel, His Eminence the 25th Tsem Rinpoche for his invaluable guidance, love, care, support and trust without whom I would not have accomplished what I have so far and be who I am today.

Humbly,

Pastor Adeline

- History

- Vows Type

- Nun’s Order

- Refuge Vows

- Five Precepts

- Eight Precepts

- Pratimoksha Vows

- Bodhisattva Vows

- Tantric Vows

- Other Vows

- Broken Commitments

Homage to Shakyamuni, guru and Victorious One.

I make offerings to you.

I take refuge in you.

OM MUNI MUNI MAHAMUNIYE SOHA

History

Some 2,550 years ago, after the Buddha attained enlightenment, he was hesitant to teach the Dharma he had realised because he felt that no one would be able to understand the subtle aspects of his teachings. However, the gods Brahma and Indra descended and implored the Buddha to teach. They did this by telling the Buddha that the world would continue to suffer endlessly if the Buddha decided not to teach. In addition, there would be at least a few people who would be able to understand and grasp even the most difficult aspects of the Dharma.

Out of great compassion, the Buddha finally accepted their request and went to Sarnath and taught the Four Noble Truths to his five former companions in the Deer Park. Soon after, a small group of young men from nearby Varanasi also joined the Buddha, thereby beginning the first monastic community. At this early stage, the monastic community would admit candidates by following practical guidelines set by the Buddha to avoid clashes with the secular authorities for harbouring criminals, those who abandoned the army, escaped slavery especially those bound to royal service, along with those suffering from contagious diseases such as leprosy. These people are barred from joining the monastic community for obvious practical reasons.

The Buddha preaching his first sermon to the five monks at Deer Park in Varanasi.

Furthermore, those under the age of 20 would not be admitted into the community as well. This is to avoid unnecessary trouble and to instill the public’s respect for the monastic community and especially the Dharma teachings. Through this, the Buddha taught members of the monastic community to be respectful of local customs and to always act respectfully. This is so that people will have a good impression of Buddhism and respect it in return.

The early monastic communities founded by the Buddha were small, with no more than 20 men in each community. Each of them were autonomous, following their own set of monastic boundaries for seeking alms. Each member of the community decided the actions and decisions by democratic vote amongst its members. In order to avoid dissension, there was no single authority figurehead. Instead, the Buddha instructed his communities to take the Dharma teachings as the authority. If necessary, the monastic rules could even be changed but all changes had to be agreed upon by consensus of the entire community.

When the Buddha visited Rajagriha city, King Bimbasara came to pay homage to the Buddha and his disciples.

Later when the Buddha returned to Magadha, King Bimbisara invited him to Rajagriha and became his patron and disciple. It was there that Shariputra and Maudgalyayana also joined the Buddha’s growing monastic order and became the Buddha’s closest disciples. At that time, King Bimbisara suggested to the Buddha to adopt some customs from other spiritual mendicant groups such as the Jains to hold quarter-monthly assemblies. During this time, members of the group assembled at the start of each quarter phase of the moon to discuss the teachings. In doing so, the Buddhas was open to suggestions and would even follow the customs of that time.

Shariputra also suggested to the Buddha to formulate rules to add to the monastic discipline. The Buddha however, decided that it was best not to institute a vow until a specific problem arose in order to avoid a similar incident from recurring. This policy was followed with respect to both destructive incidents and mild disruptive incidents. The former was outright harmful to those committing them and the community at large, while the latter was disruptive only to certain parties involved. Thus, the rules of discipline were pragmatic and formulated on an ad hoc basis with the Buddha’s main consideration being to develop monastic rules that were proven by experience, in order to avoid problems and not cause any offense.

The Buddha encouraging his first sixty arahant disciples to preach the Dharma for the welfare and happiness of all beings.

The Buddha’s purpose for laying down rules of discipline was for the growing monastic community to govern the lives of monks and nuns based on the spirit of the Buddha’s teachings. Furthermore, these rules contain procedures and etiquette that support a harmonious and respectful relationship between the Guru and disciple within the monastic context, as well as between the monastic and lay practitioners who are generous benefactors providing for the basic needs of the monastic community. All of these rules make up what is known as the vinaya or the pratimoksha vows.

This code of conduct was essential to instill harmony as the small monastic groups evolved into larger, more complex spiritual communities in which it was inevitable that a sangha member would act in an unskillful (harmful) manner. The Buddha laid down a suitable penalty for each transgression whenever it was brought to his attention. Thus, the vinaya was developed based on the Buddha’s experience handling each incident one at a time. Subsequently, the precedence for deterrent measures for future examples of misconduct were established during the Buddha’s time.

Types of Vows

Apart from the vinaya, various Buddhist practitioners also hold other sets of vows including refuge vows, five precepts, eight Mahayana precepts, bodhisattva vows and tantric vows. These vows are taken by Buddhist practitioners at different periods of their journey towards spiritual awakening.

In the beginning, the refuge vows are the basis of all vows and it is taken to change our negative gross habituations into positive ones while officially marking one’s entry onto the Buddhist path. It is a spiritual commitment and a statement of our belief and faith in the Buddha’s teachings. In addition to that, the refuge vows are the basis of future tantric initiations and higher practices. We cannot receive tantra without receiving the refuge vows first.

H.E. the 25th Tsem Rinpoche giving a Dharma talk before conferring the refuge vows to a group students at Kechara House, the Dharma centre in the city.

The five precepts are essentially a guideline in the most fundamental of human ethical behaviour. The eight Mahayana precepts are vows normally taken on auspicious and holy days such as Wesak Day and during retreats in order to enhance the accumulation of merit for 24 hours. One can take the vows again and again.

The bodhisattva vows encompass aspiring bodhicitta and engaged bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is the spontaneous wish to attain full enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings as embodied by a bodhisattva. Aspiring bodhicitta is a prayer to develop this wish to benefit others, while engaged bodhicitta is mindfully turning our daily activities into actions to benefit others. The bodhisattva vows are a guideline to develop this altruistic aspiration with the 18 root vows and 46 auxiliary vows.

Lastly, the tantric vows are given only during the highest yoga tantra initiations. The tantric vows are to facilitate the development of spiritual attainments through our tantric practice. As initiations are given rather freely nowadays, there are times where people’s first exposure to Buddhism is through an initiation where refuge vows are also given as part of the initiation ceremony. If the recipient does not consider oneself to be Buddhist after that, then one has not taken the initiation as the refuge vows are the root of all vows and attainments. In that case, one has also not taken the bodhisattva or the tantric vows either.

Refuge vows are the root of all vows and the roots of all our spiritual attainments.

These vows or rules serve as the means to develop virtuous determination to abandon misdeeds so that we are able to reinforce our practice with the merit accumulated and to develop virtuous states of mind. Therefore, when we take vows, we are determined and committed to embark on a journey of mind transformation as a tool to reach our goal of mind awakening guided by our spiritual guide.

While upholding our vows and commitments, we continue to generate merit regardless of whether we are asleep or if we are engaged in ordinary actions. In this way, we are also able to create tremendous amounts of merits to fuel our practice in order to gain attainments and also for our future lives.

Founding the Monastic Order of Nuns

The Buddha established the female monastic community towards the later part of his life at the request of his aunt Mahaprajapati. According to earlier sources, the Buddha was initially reluctant to start a female order but decided it would be possible by prescribing more vows for the nuns as compared to the monks. According to contemporary norms of the time, females were deemed to bring ill repute and so the Buddha sought to avoid contempt of the community at large. Hence the nun community would need to be exemplary and above all suspicion of immoral behaviour with additional vows. In doing so, the Buddha’s concern about the premature end to his teachings would be avoided.

Mahaprajapati requesting permission from the Buddha to establish the nun’s order.

Although in reality, there was no problem with establishing an order of nuns, the Buddha had to overcome ancient Indian prejudice against women that was prevalent at that time. On top of that, he had to prevent ordinary people of that time from developing wrong views about the Buddhist teachings as anti-establishment and as a counter-culture. Therefore, it became necessary for more rules to be prescribed for the nuns in order to avoid these two pitfalls skillfully.

In addition, the Buddha also encouraged new disciples who previously supported other religious communities to continue supporting that community. Within the monastic order, the Buddha instructed its members to take care of each other because they were all members of the same Buddhist family. This is an important precept for all lay Buddhists as well.

Refuge Vows

In Buddhism, taking refuge and upholding the refuge vows is a ritual, commitment, and a statement of one’s faith. This is for a person who has decided to begin a spiritual journey based on the Buddha’s teachings. The refuge vows are bestowed by a qualified spiritual guide with the core element that our commitment is to seek liberation from suffering by taking refuge in the Three Jewels – Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. In Tibetan Buddhism, the spiritual guide element is also included in the Buddha Jewel.

The 17 Panditas of Nalanda

The biggest enemy and obstruction on our path to enlightenment is the self-cherishing mind. It is an often lonely and difficult path as we struggle to work on our selfish mind while having to overcome external problems and obstacles that have arisen due to this self-cherishing mind.

When we take refuge, we are committing ourselves towards uprooting the selfish mind using mindfulness, focus and determination. The self-cherishing mind is the deep-seated mind that seeks happiness only for oneself. By taking refuge, we are making an affirmation to the Three Jewels in the presence of our spiritual guide that we will refrain from negative actions that bring suffering. By taking the refuge vows, we make a sacred commitment to uproot our ‘inner enemy’ and that we will not retaliate to those who hurt us, take advantage of us or disappoint us. We make this commitment to the Three Jewels and most importantly to ourselves because we wish to overcome suffering and gain attainments. As mentioned in the Short Perfection of Wisdom Sutra, “if the merit from taking refuge had form, the three realms will be too small to hold it.” In other words, the merit accruing from the act of taking refuge is immeasurable.

The refuge vows consist of the following commitments, which focuses on self-discipline and refraining from the 10 non-virtuous actions through our Three Doors – body, speech and mind:

Three of the body:

- killing

- stealing

- sexual misconduct

Four of the speech:

- divisive speech

- harsh words

- idle chatter

- lying

Three of the mind:

- envy

- hatred and malicious intent

- wrong views

In addition to the vows, there are the refuge commitments for one to uphold:

- Do not go for refuge in samsaric gods or teachers who contradict Buddha’s view

- Always regard any image of a Buddha as an actual Buddha

- Do not harm others

- Always regard any Dharma scriptures as the actual Dharma Jewel

- Do not be influenced by people who reject the Buddha’s teachings

- Always regard anyone who wears the robes of an ordained person as the actual Sangha Jewel

- Always go for refuge to the Three Jewels again and again remembering their good qualities and the differences between them

- Always offer the first portion of anything we eat and drink to the Three Jewels, while remembering their kindness

- Always encourage others to go for refuge with compassion

- Always go for refuge at least three times during the day and three times during the night, while remembering the benefits of going for refuge

- Always perform every action with complete trust in the Three Jewels

- Never forsake the Three Jewels even as a joke or at the cost of our lives.

The benefits of going for refuge:

- To become a Buddhist

- To establish the foundation for taking all vows

- To purify the negative karma that we have accumulated in the past

- To accumulate a vast collection of merits daily

- To be held back from falling into the lower realms

- To be protected from harm caused by humans and non-humans.

Five Precepts

The five precepts encapsulate many aspects of the core teachings of the Buddha, especially on cause and effect (karma), renunciation, patience and honesty. The five precepts also condense the main aspects of the refuge vows. Therefore, practitioners who are taking refuge may also take the five precepts or a combination of the five. Female and male lay practitioners can choose to hold all five precepts and by tradition, they are called an upasika (female) or upasaka (male) in Sanskrit, which literally means ‘attendant’ or ‘lay vow-holder’. The five precepts are:

- Refrain from killing living beings

- Refrain from taking what is not given

- Refrain from sexual misconduct

- Refrain from telling lies

- Refrain from intoxicants including cigarettes, alcohol, mind-altering drugs such as marijuana and any other substance that loosens one’s control.

The five precepts are not formulated as imperatives, but as training rules that Buddhist practitioners undertake voluntarily to facilitate their spiritual practice.

Each precept has profound meaning and tremendous benefits for the practitioner. Nevertheless, it is important for us to understand that the precepts are meant to be upheld as a practice and not meant to be used as a yardstick to judge another person’s behaviour.

The benefits of holding the five precepts are:

- One will have a long, magnificent and illness-free life in this life and in all future lives by refraining from killing

- One will have perfect enjoyments without harm from others in this life and in all future lives by refraining from stealing

- One will have a good body with a beautiful complexion and complete sense organs in this life and in all future lives by abandoning sexual misconduct

- One will not be cheated, and others will take heed of what one says in this life and in all future lives by refraining from lying

- One will have stable mindfulness and awareness, clear senses and perfect wisdom in this life and in all future lives by refraining from intoxicants.

Eight Mahayana Precepts

The eight Mahayana precepts are commonly taken on auspicious days, during retreats or on other days of special significance to the practitioner as suggested by the spiritual guide. The precepts are usually taken for 24 hours at a time. In addition to that, we have the option to take the precepts again the following day. These precepts consist of the five precepts and an additional three precepts as follows:

- Refraining from taking food after lunch

- Refraining from entertainment such as dancing, singing and listening to music, as well as using perfumes, ornaments, and other items used to beautify a person

- Refraining from using high or luxurious seats and beds.

“We should train ourselves not to become engrossed in any of the thoughts continuously arising in our mind. Our consciousness is like a vast ocean with plenty of space for thoughts and emotions to swim about and we should not allow our attention to be distracted by any of them.” — Lama Thubten Yeshe

A special note to take into consideration is that in taking the eight precepts, the sexual misconduct precept becomes a commitment to refrain from all sexual activity even with one’s legal spouse.

The benefits of holding the additional three precepts:

- One will receive praise and respect from others, have proper bedding and traveling vehicles in this life and in all future lives by refraining from using high or luxurious seats and beds

- One will have abundant and perfect crops and will obtain food and drink without effort in this life and in all future lives by refraining from taking food after lunch

- One will have a body with pleasant scent, colour and shape and many auspicious marks in this life and in all future lives by refraining from using perfumes, ornaments, and other items used to beautify a person

- One will have a subdued body and mind, and one’s speech will continually be pleasant in this life and in all future lives by abandoning singing and dancing.

Pratimoksha Vows

The pratimoksha vows comprise of the basic rules of monastic discipline. The novice monks and nuns take 36 vows, while a fully-ordained monk and nun (Tibetan: gelong, gelongma; Sanskrit: bhikshu, bhikshuni) are governed by 227 to 354 vows, depending on the various traditions. The nuns and monks ordained in the Tibetan tradition follow the vows set forth in the Mulasarvastivada school of monastic discipline.

Monks praying under the sacred banyan tree in Bodhgaya. It was here that the Buddha achieved enlightenment.

In the 8th Century, the Indian Abbot Shantarakshita brought the Mulasarvativada school of vinaya to Tibet when he was invited to visit there by King Trisong Detsen. Shantarakshita ordained the first seven monks and formed the first monastic community, thereby establishing Tibet’s first Buddhist monastic order of the Mulasarvastivada.

The pratimoksha vows are meant to be a lifetime commitment. Therefore, the motivation must be a purely spiritual one and cannot be anything less or one will not be able to hold the vows for long. Although some lay people can practice well without ordination, most lay people find it difficult to practice.

On the other hand, just because the Buddha advocated monastic ordination, it does not mean that everyone is suitable to become monks or nuns due to the lack of knowledge, karma and merit. Ordination requires a lot of merit and less inner obstacles to begin with. With little inner obstacles, there will also be less outer obstacles that may arise to hinder one’s ordination.

The Buddha has explained many benefits of ordination in his sutra teachings including being able to enjoy the glory of a radiant body, effortless fame, good qualities, praise by others and gaining of happiness. When someone’s vows are pure, no one will be able to harm them as they do not create the cause to be harmed. Others will not fear to be harmed by them also. It is logical therefore to say that beings will be safe around one who has pure vows.

The Samye Monastery is the first Buddhist monastery built in Tibet under the patronage of King Trisong Detsen who sought to revitalise Buddhism. Prior to that, the Indian master Shantarakshita made the first attempt to construct the monastery while teaching Dharma to the Tibetans. He set out to build a structure there after finding the Samye site auspicious. However, the building would always collapse after reaching a certain stage. The construction workers were terrified and believed that a vicious spirit in a nearby river was causing this trouble.

The vinaya helps to protect the mind while the monasteries and nunneries protect the individual physically by living in the right environment. Many precepts in the vinaya were given by the Buddha to guide our actions with the additional intention to protect others from criticising and developing wrong views about the sangha. When the sangha hols their vows purely, others will develop faith in the sangha, thus planting the seeds for liberation and enlightenment in their mind.

A pure nun and monk has great power to bless beings when they pray for others. They are a suitable object for making offerings to. By the power of their vows they bless the giver, allowing them to accumulate merit. In fact, merely by respecting the sangha, others can generate a lot of merit for the success of their own spiritual practice and endeavours. Lay practitioners venerate the sangha because they recognise the qualities of perseverance and dedication to Dharma practice. Lay practitioners also respect the tremendous Dharma work that the sangha do, as well as leading a spiritual life that lay practitioners rarely have the time for.

Without Dharma practice and the teachings that protect one’s mind, it is not possible to benefit others in the best way according to what they need. In fact, how can anyone benefit others when we cannot really find peace, satisfaction, happiness, or fulfillment for ourselves? As the Sutra on Having Pure Ethics says:

“Monks, it is easy to give up your life and die — but not so for the decline or destruction of your ethics. Why so? If you give up your life and die, then the life of this rebirth comes to an end but owing to the decline or destruction of your ethics, you give up happiness for tens of millions of eons, you separate yourself from the lineage, you abandon happiness, and experience a great downfall.”

The direct benefits of ordination:

For one who no longer suffers from desire and has achieved Arahanthood, they will receive the following benefits:

- All previous suffering from the past will disappear

- The new suffering that might occur will have no chance to take its effect

- One will become a model of good conduct and moral fibre for those in its community.

According to Dharma:

- One will be pure both physically and spiritually

- One will be a kind and generous person

- One will have wisdom and compassion.

The indirect benefits of ordination:

Benefits for those around the sangha:

- Friends and families will be connected with the Dharma and have the opportunities to learn and practice Dharma

- One will be a good member of society and the surrounding community due to the works that a member of the sangha does.

According to Dharma:

- One will be the upholder of the Buddha’s teachings who bears the responsibility for passing the precious teachings on to future generations.

A fully ordained monk holds 253 vows according to the Mulasarvastivada school of vinaya. These are broadly divided into five categories with sets of 10, 20 and so forth as follows:

I. First Class:

A. 4 Defeats

- Being unchaste

- Stealing

- Homicide

- Lying

II. Second Class:

A. 13 Remainders

- Emission of semen

- Lustfully making physical contact

- Speaking words related to sex

- Commending services

- Baseless accusation

- Subverting lay people

- Being displeased with advice, and so forth.

III. Third Class: 120 Downfalls

A. 30 Forfeiting Downfalls:

- Forfeiting downfalls, first set of 10:

– retaining cloth for 10 days

– being separated from one’s Dharma robes

– receiving cloth from a gelongma, and so forth.

- Forfeiting downfalls, second set of 10:

– making a silk rug

– making a rug of only black wool

– not to patch with a hand span

– transporting wool

– taking gold and silver

– engaging in financial dealings, and so forth.

- Forfeiting downfalls, third set of 10:

– retaining an alms bowl

– seeking out an alms bowl

– engaging a weaver to weave cloth

– increasing what is already woven

– reclaiming a gift, and so forth.

B. 90 Simple Downfalls:

- Simple downfalls, first set of 10:

– telling a lie

– criticising another gelong

– divisive speech

– reviving a dispute

– falsely accusing another of showing favouritism, and so forth.

- Simple downfalls, second set of 10:

– destroing seeds or a plant

– being deaf to advice

– being deaf to eviction, and so forth.

- Simple downfalls, third set of 10:

– teaching Dharma when not appointed,

– teaching Dharma beyond sunset, and so forth.

- Simple downfalls, fourth set of 10:

– eating many meals

– taking more than two or three alms bowlfuls

– eating at the wrong time, and so forth.

- Simple downfalls, fifth set of 10:

– using water with creatures in it

– standing near a place where lay men and women are preparing for sexual action, and so forth.

- Simple downfalls, sixth set of 10:

– causing food to be cut off

– touching fire

– withdrawing consent, and so forth.

- Simple downfalls, seventh set of 10:

– killing an animal

– creating regret

– tickling

– playing in water, and so forth.

- Simple downfalls, eighth set of 10:

– going along a road in company of a thief

– confering full ordination on someone not yet 20 years, and so forth.

- Simple downfalls, ninth set of 10:

– visiting a king’s palace at night

– deprecating

– fabricating a needle case, and so forth.

IV. Fourth Class: Four Matters to Be Confessed Individually

- receiving food from a gelongma

- breaking the training by entering a house, and so forth.

V. Fifth Class: 112 Misdeeds

- Misdeeds, first set of 10:

Arise from the wearing of robes

– the misdeeds of not wearing the monastic shamtab (lower robe) round

– wearing it hitched up high

– knees not covered

– hung low

– covering the ankles

– stretching down on one side like an elephant trunk

– top folded above navel, and so forth

– wearing the upper robes not round

– wearing it hitched up high and wearing it low, and so forth.

- Misdeeds, second set of 20:

Go to houses

– going to houses without maintaining mindfulness, and so forth

– going with Dharma robes hoisted up, and so forth

– going jumping, and so forth

– going swinging the arms, and so forth.

- Misdeeds, third set of 9:

Sitting in houses

– sitting down on a seat without checking

– sitting by dropping down heavily, and so forth.

- Misdeeds, fourth set of 8:

Receiving food

– not receiving food properly

– receiving level with the brim of the bowl, and so forth.

- Misdeeds, fifth set of 21:

Eating food

– not eating with good manners

– eating in big gulps, and so forth.

- Misdeeds, sixth set of 14:

Use of the alms bowls

– denigrating another’s begging bowl, and so forth

– putting leftover food in the bowl, and so forth.

- Misdeeds, seventh set of 26:

Teaching the Dharma

– teaching the Dharma while standing to the seated, and so forth

– teaching the Dharma to one whose head is covered with a cloth, and so forth.

- Misdeeds, eighth set of 3:

– to be performed.

- Misdeeds, ninth set of 1:

Going

– discharging urine, faeces, etc. into water, and so forth

– climbing tree above a man’s height without necessity.

These are the 253 vows which a monk must guard against while a nun has 373 vows. Within the monk vows, there are 14 vows that factor in the possibility of infraction to occur, this applies to a nun as well. In other words, those 14 vows are applicable to both male and female as compared to the rest which are tailored according to gender.

Similar to the Theravada tradition, the rules of ordination in the Mulasarvativada vinaya tradition are threefold: for one to take the vows that have not already been taken, the ways to guard them without causing degeneration and the ways to restore the vows if they have degenerated. Naturally, ordained monks and nuns have to study and practice the vinaya. They also take part in the bi-monthly confessional and vow restoration ceremony (sojong). Monasticism is regarded with the highest reverence as the foundation of the teachings of the Buddha.

The Buddha instituted the recitation of the vows at the bi-monthly monastic assembly, with monks openly admitting to any infractions. Expulsion from the community followed for the most serious infractions, otherwise just the disgrace of probation.

In order for one to keep the vows pure, monastic practitioners must know about the four doors through which infractions can occur and they should close these doors:

- ignorance, not knowing the boundary of what does and does not constitute a downfall

- lack of respect for the vows and commitments, the Three Jewels, and so forth even if we are aware of the boundaries

- heedlessness, lack of consciousness, mindfulness, and introspective awareness, even if we have respect

- being overwhelmed by strong afflictions, even when we know the precepts and commitments, respect them and are conscientious.

It is important to uphold all vows in order to progress on the path and attain the ultimate goal of enlightenment. This is because vows are the foundation of Buddhadharma and are beneficial towards the training of higher concentration and wisdom.

Bodhisattva Vows

The bodhisattva vows are taken by Mahayana Buddhists with the aspiration to attain enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings. Once we have taken these vows, we have started our spiritual journey on the bodhisattva path until we attained enlightenment. The bodhisattva vows descend down in two major lineages. The Lineage of Nagarjuna descended from Buddha Shakyamuni to Manjushri and then to Nagarjuna, while the Lineage of Asanga descended from Buddha Shakyamuni to Maitreya and then to Asanga. These two lineages later arrived in Tibet via the Mahayana masters of ancient India.

The bodhisattva vows offer excellent guidelines for the types of behaviour to avoid if we wish to benefit others in as pure and full a way as is possible.

The bodhisattva vows are harder to observe than the pratimoksha vows as its main discipline is maintaining the subtle and difficult to establish, right mental attitude and understanding. However, it is also very beneficial and powerful towards the realisation of the Bodhicitta intent in our mind. Our actions then will only benefit others.

The bodhisattva vows include both the root and auxiliary vows. There are 18 root vows, 46 auxiliary vows, 39 downfalls and 4 conditions that constitute a vow transgression.

The 18 Root Vows

One must abandon:

- Praise of oneself and belittling others

- Not sharing Dharma and one’s wealth with others

- Not forgiving even when another apologises

- Doubting and denying the Mahayana doctrine

- Taking offerings intended for the Three Jewels

- Abandoning the doctrine

- Causing an ordained person to disrobe

- Committing one of the five crimes of immediate retribution

- Holding perverted views

- Destroying places such as towns

- Teaching emptiness to those untrained

- Discouraging others from seeking enlightenment

- Causing others to break vows of individual liberation

- Belittling those who follow the path of individual liberation

- Proclaiming false realisations

- Accepting gifts of articles that have been misappropriated from the belongings of the Three Jewels

- Laying down harmful regulations and passing false judgement

- Giving up the pledge of bodhicitta.

A complete infraction of any of the root vows requires association with the four conditions that constitute a vow transgression, not including cases of giving up the pledge of bodhicitta and holding perverted views. The four conditions that constitute a vow transgression are:

- Unmindful of the disadvantages

- Continuing to indulge in the infraction

- Indulging in the infraction with great pleasure and delight

- Lack of shame and conscience.

The 46 Auxiliary Vows

One must abandon the following actions:

Seven downfalls related to generosity

- Not making offerings to the Three Jewels every day

- Acting out desirous thoughts because of discontent

- Not paying respect to those senior to one in ordination and in taking bodhisattva vows

- Not answering questions out of negligence though one is able to do so

- Not accepting invitations selfishly due to pride, the wish to hurt others’ feelings, or anger and laziness

- Not accepting others’ gifts simply to hurt the other or out of jealousy, anger, etc.

- Not giving Dharma to those who wish to learn.

Nine downfalls related to the practice of morality

- Ignoring and insulting someone who has committed any of the five heinous crimes or defiled his or her vows of individual liberation, or treating him or her with contempt

- Not observing the precepts of moral conduct because one wishes to ingratiate oneself with others

- Complying with the minor precepts when the situation demands one’s disregard of them for the greater benefit of others

- Not committing one of the seven negative actions of the body and speech when universal love and compassion deem it necessary in a particular instance

- Accepting things which are acquired through one of the five wrong livelihoods

- Wasting time on frivolous actions (such as carelessness, lack of pure morality, dancing, playing music just for fun, gossiping) and also distracting others in meditation

- Misconceiving that bodhisattvas do not attempt to attain liberation and failing to view delusions as things to be eliminated

- Not living up to one’s percepts, thinking that doing so might decrease one’s popularity, or not correcting the undisciplined behaviour of body and speech which result in a bad reputation that limits one’s ability to carry out the tasks of a bodhisattva

- Not correcting others whom, motivated by delusions, commit negative actions. Doing so helps them to disclose and purify their actions, whereas concealing them generates suspicions of being disliked by others.

Four downfalls related to patience

- Parting from the four noble disciplines; not retaliating when scolded by others, humiliated by others, hit by others or even killed by others

- Neglecting those who are angry with you

- Refusing to accept the apologies of others

- Acting out thoughts of anger, not opposing the arousal of anger within one’s mind by reflecting upon its harmful consequences, etc.

Three downfalls related to joyous effort

- Gathering a circle of disciples out of desire for respect and material gain

- Wasting time and energy on trivial matters, not countering laziness, addiction to excessive sleep, and procrastination

- Being addicted to frivolous talk.

Three downfalls related to concentration

- Not seeking the appropriate conditions for attaining single-pointed concentration, and meditating upon it without proper guidance

- Not eliminating the obstacles to one’s concentration

- Regarding the blissful experience derived from concentration as the main purpose of single-pointed meditation.

Eight downfalls related to the perfection of wisdom

- Abandoning the doctrines of the Lesser Vehicle with the thought that the practitioners of the Greater Vehicle need not study or practice them

- Unnecessarily expanding one’s energy in the other directions despite having one’s own Greater Vehicle methods

- Pursuing non-Dharma studies to the neglect of the Dharma ones

- Studying non-Dharma subjects with great thoroughness, out of attachments to these views, and favouring them

- Abandoning the doctrines of the Great Vehicle, claiming that they are ineffective and rejecting the texts on ground of their literary style

- Praising oneself and belittling others out of arrogance and hatred

- Not attending Dharma ceremonies, discourses etc out of laziness or pride

- Despising one’s Guru and not relying on his words.

Twelve downfalls related to ethics and helping others

- Not helping those who need assistance

- Avoiding the task of caring for sick people

- Not working to alleviate other’s suffering, such as the seven types of frustrations: being blind, deaf, lame, exhausted from fatigue, depressed, abused and rebuked by others, and suffering from hindrances to a calm and single-pointed mind

- Not showing the Dharma to those recklessly caught up in the affairs of this life alone

- Not repaying the kindness of others

- Not consoling those who have mental grief, such as that caused by separation from loved ones

- Not giving material aid to those who are in need of it

- Not taking care of one’s circles of disciples, relatives and friends by giving them teaching and material aid

- Not acting in accordance with others’ wishes

- Not praising those who deserve praise and their good qualities

- Not preventing harmful acts to the extent permitted by circumstances

- Not employing physical prowess of supernatural powers, if one possesses them, at the time needed.

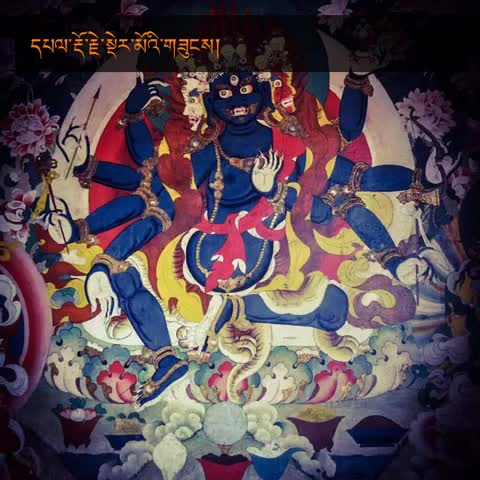

Tantric Vows

Vajrayogini herself appeared to His Holiness Pabongka Rinpoche in a vision, and told him that anyone who receives her practice within four generations of Pabongka Rinpoche, will be able to enter her paradise Dakpo Kachö within seven lifetimes. After these four generations, it reverts to the normal 14 lifetimes.

This is similar to the bodhisattva vows in terms of having root and secondary tantric vows that we uphold until we achieve enlightenment. The tantric vows mainly emphasise vows that foster the realisation and perfection of the union of wisdom and skillful means and accomplishing simultaneously the goal of oneself and others.

There are 14 root tantric vows and this excludes the fifth root vow – when we give up the aspiring bodhichitta. We are to refrain from fourteen actions listed below. Any of the 13 root downfalls that are committed with the four binding factors, from the moment of the motivation right to the infraction of the vow, until the completion of the transgression constitutes the loss of the tantric vows. The 14 common tantric root downfalls according to the Common Root Tantric Vows are:

- Scorning or deriding our vajra masters

The object is any teacher from whom we have received empowerment, subsequent permission, or mantra into any class of tantra, full or partial explanation of any of their texts, or oral guidelines for any of their practices. Scorning or deriding such masters means showing them contempt, faulting or ridiculing them, being disrespectful or impolite, or thinking or saying that their teachings or advice were useless. Having formerly held them in high regard, with honour and respect, we complete this root downfall when we forsake that attitude, reject them as our teachers, and regard them with haughty disdain. Such scornful action, then, is quite different from following the advice in The Kalachakra Tantra to keep a respectful distance and no longer study or associate with a tantric master whom we decide is inappropriate for us, not properly qualified, or who acts in an improper manner. Scorning or belittling our teachers of only topics that are not unique to tantra, such as compassion or voidness, or who confer upon us only safe direction (refuge), or either pratimoksha or bodhisattva vows, does not technically constitute this first tantric root downfall. Such actions, however, seriously hamper our spiritual progress.

- Transgressing the words of an enlightened one

The objects of this action are specifically the contents of an enlightened being’s teachings concerning pratimoksha, bodhisattva, or tantric vows – whether that person be the Buddha himself or a later great master. Committing this downfall is not simply to transgress a particular vow from one of these sets, having taken it, but to do so with two additional factors present. These are fully acknowledging that the vow derives from someone who has removed all mental obscuration, and trivializing it by thinking or saying that violating it brings no negative consequences. Trivializing and transgressing either injunctions we know an enlightened being has imparted other than those in any of the three sets of vows we have taken, or advice we do not realize an enlightened being has offered, does not constitute a tantric root downfall. It creates obstacles, however, in our spiritual path.

- Because of anger, faulting our vajra brothers or sisters

Vajra brothers and sisters are those who hold tantric vows and have received an empowerment into any Buddha-figure system of any class of tantra from the same tantric master. The empowerments do not need to be received at the same time, nor do they need to be into the same system or class of tantra. This downfall occurs when, knowing full well that certain persons are our vajra brothers or sisters, we taunt or verbally abuse them to their face about faults, shortcomings, failings, mistakes, transgressions, and so on that they may or may not possess or have committed, and they understand what we say. The motivation must be hostility, anger, or hatred. Pointing out the weaknesses of such persons in a kind manner, with the wish to help them overcome them, is not a fault.

- Giving up love for sentient beings

Love is the wish for others to be happy and to have the causes for happiness. The downfall is wishing the opposite for any being, even the worst serial murderer – namely, wishing someone to be divested of happiness and its causes. The causes for happiness are fully understanding reality and the karmic laws of behavioral cause and effect. We would at least wish a murderer to gain sufficient realization of these points so that he never repeats his atrocities in future lives, and so eventually experiences happiness. Although it is not a tantric root downfall to ignore someone whom we are capable of helping, it is a downfall to think how wonderful it would be if a particular being were never happy.

- Giving up bodhichitta

This is the same as the eighteenth bodhisattva root downfall, and amounts to giving up the aspiring state of bodhichitta by thinking we are incapable of attaining Buddhahood for the sake of all beings. Even without the four binding factors present, such a thought voids us of both bodhisattva and tantric vows.

- Deriding our own or others’ tenets

This is the same as the sixth bodhisattva root downfall, forsaking the holy Dharma, and refers to proclaiming that any of the Buddhist textual teachings are not Buddha’s words. “Others’ tenets” refer to the sutras of the shravaka, pratyekabuddha, or bodhisattva (Mahayana) vehicles, while “our own” are the tantras, also within the Mahayana fold.

- Disclosing confidential teachings to those who are unripe

Confidential (secret) teachings concern actual specific generation (bskyed-rim) or complete stage (rdzogs-rim) practices for realizing voidness that are not shared in common with less advanced levels of practice. They include details of specific sadhanas and of techniques for actualizing a greatly blissful deep awareness of voidness with clear light mental activity. Those unripe for them are people who have not received the appropriate level of empowerment, whether or not they would have faith in these practices if they knew them. Explaining any of these unshared, confidential procedures in sufficient detail to someone whom we know fully well is unripe so that he or she has enough information to attempt the practice, and this person understands the instructions, constitutes the root downfall. The only exception is when there is a great need for explicit explanation, for example to help dispel misinformation and distorted, antagonistic views about tantra. Explaining general tantra theory in a scholarly manner, not sufficient for practice, is likewise not a root downfall. Nevertheless, it weakens the effectiveness of our tantric practice. There is no fault, however, in disclosing confidential teachings to interested observers during a tantric empowerment.

- Reviling or abusing our aggregates

Five aggregates (Skt. skandha), or aggregate factors, constitute each moment of our experience. These five are: (a) forms of physical phenomena such as sights or sounds, (b) feelings of happiness or unhappiness, (c) distinguishing one thing from another (recognition), (d) other mental factors such as love or hatred, and (e) types of consciousness such as visual or mental. In brief, our aggregates include our bodies, minds, and emotions.

Normally, these aggregate factors are associated with confusion (zag-bcas) – usually translated as their being “contaminated.” With anuttarayoga tantra practice, we remove that confusion about reality and thus totally transform our aggregates. Instead of each moment of experience comprising five factors associated with confusion, each moment eventually becomes a composite of five types of deep awareness that are dissociated from confusion (zag-med ye-shes), and which are the underlying natures of the five aggregates. These are the deep awareness that is like a mirror, of the equality of things, of individuality, of how to accomplish purposes, and of the sphere of reality (Skt. dharmadhatu). Each of the five is represented by a Buddha-figure (yi-dam): Vairochana, and so on, called in the West “the five dhyani-Buddhas.”

An anuttarayoga empowerment plants the seeds to accomplish this transformation. During generation stage practice, we cultivate these seeds by imagining our aggregates already to be in their purified forms through visualizing them as their corresponding Buddha-figures. During complete stage practice, we bring these seeds to maturity by engaging our aggregates in special yoga methods to manifest clear light mental activity with which to realize the five types of deep awareness.

The eighth root downfall is either to despise our aggregates, thinking them unfit to undergo this transformation, or purposely to damage them because of hatred or contempt. Practicing tantra does not call for a denial or rejection of the sutra view that regarding the body as clean and in the nature of happiness is a form of incorrect consideration (tshul-min yid-byed). It is quite clear that our bodies naturally get dirty and bring us suffering such as sickness and physical pain. Nevertheless, we recognize in tantra that the human body also has a deeper nature, rendering it fit to be used on many levels along the spiritual path to benefit others more fully. When we are unaware of or do not acknowledge that deeper nature, we hate our bodies, think our minds are no good, and consider our emotions as evil. When we hold such attitudes of low self-esteem or, in addition, abuse our bodies or minds with masochistic behavior, unnecessarily dangerous or punishing life styles, or by polluting them with recreational or narcotic drugs, we commit this tantric root downfall.

- Rejecting voidness

Voidness (emptiness) here refers either to the general teaching of The Sutras on Far-Reaching Discriminating Awareness (Skt. Prajnaparamita Sutras) that all phenomena, not only persons, are devoid of impossible modes of existence, or to the specifically Mahayana teachings of the Chittamatra or any of the Madhyamaka schools concerning phenomena being devoid of a particular impossible way of existing. To reject such teachings means to doubt, disbelieve, or spurn them. No matter which Mahayana tenet system we hold while practicing tantra, we need total confidence in its teachings on voidness. Otherwise, if we reject voidness during the course of our practice, or attempt any procedure outside of its context, we may believe, for example, that our visualizations are concretely real. Such misconceptions only perpetuate the sufferings of samsara and may even lead to a mental imbalance. It may be necessary, along the way, to upgrade our tenet systems from Chittamatra to Madhyamaka – or, within Madhyamaka, from Svatantrika to Prasangika – and, in the process, refute the voidness teachings of our former tenet systems. Discarding a less sophisticated explanation, however, does not mean leaving ourselves without a correct view of the voidness of all phenomena that is appropriate to our levels of understanding.

- Being loving toward malevolent people

Malevolent people are those who despise our personal teachers, spiritual masters in general, or the Buddhas, Dharma, or the Sangha, or who, in addition, cause harm or damage to any of them. Although it is inappropriate to forsake the wish for such persons to be happy and have the causes for happiness, we commit a root downfall by acting or speaking lovingly toward them. Such action includes being friendly with them, supporting them by buying goods they produce, books that they write, and so on. If we are motivated purely by love and compassion, and possess the means to stop their destructive behavior and transfer them to a more positive state, we would certainly try to do so, even if it means resorting to forceful methods. If we lack these qualifications, however, we incur no fault in simply boycotting such persons.

- Not meditating on voidness continually

As with the ninth tantric root downfall, voidness can be understood according to either the Chittamatra or Madhyamaka systems. Once we gain an understanding of such a view, it is a root downfall to let more than a day and night pass without meditating on it. The usual custom is to meditate on voidness at least three times during the course of each day and three times each night. We need to continue such practice until we have rid ourselves of all obstacles preventing omniscience (shes-sgrib) – at which point we remain directly mindful of voidness at all times. If we place a limit and think we have meditated enough on voidness before reaching this goal, we can never attain it.

- Deterring those with faith

This refers to purposely discouraging people from a particular tantric practice in which they have faith and for which they are fit vessels, with proper empowerment and so forth. If we cause their wish to engage in this practice to end, this root downfall is complete. If they are not yet ready for such practice, however, there is no fault in outlining in a realistic manner what they must master first, even if it might seem daunting. Engaging others like this, taking them and their interests seriously rather than belittling them as incapable, actually boosts their self-confidence to forge ahead.

- Not relying properly on the substances that bond us closely to tantric practice (dam-rdzas)

The practice of anuttarayoga tantra includes participating in periodic offering ceremonies known as tsog pujas. They involve tasting specially consecrated alcohol and meat. These substances symbolize the aggregates, bodily elements and, in Kalachakra, the energy-winds – ordinarily disturbing factors that have a nature of being able to confer deep awareness when dissociated from confusion and used for the path. The root downfall is to consider such substances nauseating, to refuse them on the grounds of being a teetotaler or a vegetarian, or alternatively, to take them in large quantities with gusto and attachment.

If we are ex-alcoholics and if there is the danger that tasting even a drop of alcohol might bring about a return to alcoholism, we may imagine merely tasting the alcohol when at a tsog with others. When doing so, we would merely go through the gestures of tasting the alcohol, but without actually tasting it. When offering tsog at home, we may substitute tea or juice for the alcohol.

- Deriding women

The aim of anuttarayoga tantra is to access and harness clear light mental activity to apprehend voidness so as to overcome as quickly as possible confusion and its instincts – the principal factors preventing liberation, omniscience, and the full ability to benefit others. A blissful state of awareness is extremely conducive for reaching clear light mental activity since it draws us into ever deeper, more intense and refined levels of consciousness and energy. Moreover, when blissful awareness reaches the clear light level and focuses on voidness with full understanding, it becomes the most powerful tool for clearing away the instincts of confusion.

During the process of gaining absorbed concentration, we experience increasingly blissful awareness as a result of ridding our minds of dullness and agitation. The same thing happens as we gain ever deeper understanding and realization of voidness, as a result of ridding our minds of disturbing emotions and attitudes. Combining the two, we experience increasingly intense and refined levels of bliss as we gain ever stronger concentration on ever deeper understandings of voidness.

In anuttarayoga tantra, men enhance the bliss of their concentrated awareness of voidness even further by relying on women. This practice involves relying on either actual women as a seal of behavior (las-kyi phyag-rgya, Skt.karmamudra) visualized as female Buddha-figures so as to avoid confusion, or, for those of more refined faculties, merely visualized ones alone as a seal of deep awareness (ye-shes phyag-rgya, Skt. jnanamudra). Women enhance their bliss through men in a similar fashion by relying on the fact of their being a woman. Therefore, it is a tantric root downfall to belittle, deride, ridicule, or consider as inferior a specific woman, women in general, or a female Buddha-figure. When we voice low opinion and contempt directly to a woman, with the intention to deride womanhood, and she understands what we say, we complete this root downfall. Although it is improper to deride men, doing so is not a tantric root downfall.

Without the four binding factors, we have merely weakened the vows. In other words, the vows will remain in our mental continuum if the transgression was committed without the four binding factors. In the Factors Involved in Transgressing Tantric Vows, the four binding factors are listed as follows:

- not regarding the negative action as detrimental, seeing only advantages to it, and undertaking the action with no regrets

- having been in the habit of committing the transgression before, having no wish or intention to refrain now or in the future from repeating it

- delighting in the negative action and undertaking it with joy

- having no moral self-dignity or care for how our actions reflect on others and thus having no intention of repairing the damage we are doing to ourselves and to them.

Upholding our tantric vows are essential in our tantric practice, without which we cannot gain attainments and realisations from tantric practice due to the lacking of supporting merits required for our practice.

Other vows introduced by His Eminence the 25th Tsem Rinpoche

Vegetarian vow

His Eminence the 25th Tsem Rinpoche has always been a strong advocate of vegetarianism and being kind to animals. With the advent of the modern meat processing industry, cruelty towards animals has become rampant. Therefore, His Eminence urges people to opt for vegetarian diet and for those spiritually inclined, he encourages us to take on the vegetarian vow with the right motivation.

“For fear of causing terror to living beings…Let the bodhisattva who is disciplining himself to attain Compassion, refrain from eating flesh.” — Buddha

Taking the vegetarian vow is different from just not eating meat. By taking the vow consciously in front of the Three Jewels, we reap the benefits of not eating meat every day, thereby collecting merits. This adherence is based on the precept of refraining from killing. When we eat the flesh of an animal, a living being, it means that an animal was killed for our food. Therefore, even if we did not kill the animal ourselves, the mere fact that an animal died for our consumption creates negative karma. In essence, we became the cause for the animal’s death. The core of being a vegetarian is to refrain from killing and to generate compassion for all sentient beings.

Community vows

“Community vows are vows that set the parameters for the ethical conduct of being in the community. As the community grows and expands, so too will the diversity of people and ideas coming into the community. Hence, there will be potential for human issues to arise. We have to remember that whether we are in Kechara in a spiritual capacity or purely secular, we want to accomplish our works and have harmony with each other. Not all of us may have the same goals and ideal standards but we certainly want Kechara to succeed further since we are working together. Some of us working or volunteering in Kechara may not even be Buddhist and therefore the Buddhist vows don’t apply to you but the humanistic ones are something nice to understand what we all strive for and abide.”

— His Eminence the 25th Tsem Rinpoche

The guidelines below were composed by His Eminence to foster a harmonious working environment within Kechara. It is also applicable to everyone and in any environment. It is universal and can be easily understood by a non-Buddhist as being one with the God within. In general, these vows are meant for anyone to live and work harmoniously within a community. These vows are:

- I vow to view my fellow sangha as the disciples of Buddha Shakyamuni and Je Tsongkhapa and their retinue worthy of enlightened potential and respect

- I vow to study the teachings of the Buddha in order to gain great mind transformations to benefit others continuously

- I vow to consistently and joyfully practise awareness and kindness with my sangha compatriots, serving them with happiness

- I vow to wholeheartedly honour my commitments to my fellow sangha and be consistent in my work, duties and commitments

- I vow not to engage in gossip, schism, casual negativity and instead speak with compassion, tolerance and love. To unify others and our goal with my speech and not create schism

- I vow not to indulge in games of comparison, jealousy and competition just to fulfil my desires for domination, status and consolation. I vow to let others win and help them to win in their spiritual practices

- I vow to relate to my fellow sangha from a place deep within me with friendliness and care so they can gain benefits from their spiritual practice and their interaction with me

- When my fellow sangha is speaking, I vow to listen with an open heart and mind. If they are different from my views, then I would logically and patiently share my ideas so our environment can benefit from many ideas and experiences of diverse backgrounds

- I vow to accept full responsibility for my emotions and to improve them and to communicate directly and openly with my fellow sangha in order to keep our relationship alive and genuine

- I vow to respect all religions, all forms of Buddhism and all beings who do not believe in the same religion and to look upon them as objects to love and fellow beings who deserve happiness, just the same as myself

- I vow to share my wealth, knowledge and experiences in ways that do not bring attention or ego boosts to myself

- I vow to improve my emotions, body language, speech and motivation better as time goes on and not remain stagnant and thus falling prey to angst, laziness and mind games

- I vow to study, meditate, apply the teachings I have been given and taught by Buddha so I can generate internal results resulting in positive external environments

- I vow to control my petty small desires and emotions which are troublemakers with focusing on relieving the sufferings of others

- I vow to achieve the full Buddha awakening following in the footsteps of Lord Buddha and Je Tsongkhapa.

Broken Commitments

“When you are doing a Vajrasattva practice intensely and well, you will get signs. Some of the signs will be…immediate signs will be that your mind becomes clearer. You can deal with your problems more. Even sicknesses that have been bothering you for a long time become easier to deal with. Also when you take medicine, it takes effect. Things like that. Even your financial situation will clear, definitely, definitely, because the karma is cleared. It’s very logical.” — His Eminence the 25th Tsem Rinpoche

Maintaining the vows

It is essential to learn each and every single vow we have taken and observe them accordingly. However, due to lack of knowledge, time, dedication and so forth, it might be difficult for many of us to observe them. Having said that, we should strive to do our best to be a loving person and avoid harming others. We should always be respectful to others. In this way, we move toward fulfilling the refuge and pratimoksha vows of not harming others and the bodhisattva vows of not abandoning any being.

Restoring the vows

It is necessary for us to learn how to repair any broken vows as this will undoubtedly occur from time to time due to various valid and invalid reasons. There are different methods to purify broken commitments, and the tantric means is believed to be the most powerful and effective in purifying the faults committed against any sets of vows. The purification practice through Vajrasattva recitation is common in Tibetan Buddhism. It is also one of the most powerful means of purifying negative actions created by the 10 non-virtuous actions and transgressions of precepts, vows and commitments. Together with the Four Opponent Powers, we are able to purify our negative actions and relieve ourselves of guilt and feelings of being unworthy. The Four Opponent Powers are:

- Power of Reliance

The Power of Reliance or refuge is a total reliance on Vajrasattva with faith and devotion. We see Vajrasattva as the embodiment of the power of purification due to the power of the object. This is because Vajrasattva is a fully enlightened Buddha and he is therefore without fault. Vajrasattva has long eradicated all traces of negative karma and imprints. That is why we can take refuge in him and allow his blessings to purify our negative karma of body, speech and mind.

- Power of Regret

The Power of Regret is the strong feeling of remorse for whatever negative actions we have committed consciously and unconsciously. It is through remorse that we transform our mind and habitual patterns so we do not repeat the same mistake or infraction again.

- Power of Remedy

The Power of Remedy is the actual recitation of Vajrasattva’s mantra and the meditation of Vajrasattva. Negative karma multiplies and hence, it is very important to engage in remedial practices to purify the negative karma and thereby allowing realisations and spiritual attainments to arise without hindrance.

The Hundred Syllable Purification Mantra of Vajrasattva is

OM BENZASATTO SAMAYA MANU PALAYA / BENZASATTO TENO PATITA / DIDRO MAY BHAWA / SUTO KAYO MAY BHAWA / SUPO KAYO MAY BHAWA / ANU RAKTO MAY BHAWA / SARWA SIDDHI ME PAR YATSA / SARWA KARMA SUT TSA ME / TISHTAM SHRIYAM KURU HUM / HA HA HA HA HO / BHAGAWAN SARWA TATAGATA / BENZA MA MAY MUN TSA / BENZA BHAWA MAHA SAMAYA SATTO / AH HUM PHET (At least 21x daily)

The Short Mantra of Vajrasattva is OM BENZA SATTO HUM

- Power of Restraint

The Power of Restraint is the determination from the depths of our heart to never commit these negative actions again. If we have strong determination not to commit these faults again, we will gradually change the direction of our lives. Our determination will come through understanding the faults of our previously unskilled actions and where they would lead us. We gain conviction when we contemplate on the results of negative actions.

Then, we dissolve Vajrasattva into ourselves and visualise that we have become inseparably with Vajrasattva’s body, speech and mind.

Dedication

By this merit may I attain the enlightened state of Vajrasattva, that I may be able to liberate all sentient beings from suffering.

See full explanation and visualisation of Vajrasattva practice here.

“As human practitioners of Dharma, we make mistakes; from time to time we may break our vows and commitments. When we do so, we feel that in some ways, we have let down our Gurus, and the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. We may have faced many obstacles due to unfavourable conditions and lack of time and energy, but at the same we also know that we have made lifetime commitments.”

— Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche in his Guidelines for Dharma Students

Conclusion

In conclusion, from the moment a person takes vows, they continue to collect a tremendous amount of merit day and night by living according to those vows. They also create the causes necessary for a good rebirth in the next life. If the vows are taken with the motivation to be liberated from samsara, then they become the cause to achieve renunciation. If the vows are taken with bodhicitta, then they become the cause for enlightenment.

Compared with those who do not take vows, those who have taken vows will collect merit and progress on their spiritual path swiftly and with total freedom from any negativity. All actions they do, such as shopping, sleeping, eating, or even if they are in coma, they continue to collect merit and live every second of their life meaningfully.

Most people do not live according to vows but base their lives around mundane activities, eating, sleeping, traveling, getting married and so forth. They live their lives continuously creating causes to be in samsara, fully restricted by their self-cherishing mind. However, those who live according to vows continue to collect merit, the cause of happiness for many future lives to come and eventually freedom from samsara.

Therefore, taking vows is not merely refraining from negative actions but the higher training of virtues that is the basis for the advance training of concentration. This concentration is the foundation for the higher training of wisdom that is the cause to purify samsara, without which one cannot generate bodhicitta, thus being unable to practise the tantric path and achieve enlightenment in one short lifetime during this degenerate time.

References:

- Taking Refuge in Buddha

- Taking Refuge by Pabongka Rinpoche

- Support the Kechara Pastors

- Protection from Black Magic and Spirits

- Very Important talk!! Must Listen!

- Community Vows

- For those who hold vows

- An important purification practice

- Vajrasattva and Prostrations Practice

- 6 Mind-Blowing Benefits To Your Body As A Vegetarian

- Getting Closer to Vajrayogini

- Vows and Commitments

- Life of Shakyamuni Buddha with pictures (http://namoamitabha.ws/LifeOfShakyamuniBuddhaWithPictures.html)

- Life of Shakyamuni Buddha from StudyBuddhism.com

- Common Root Tantric Vows from StudyBuddhism.com

- Factors Involved in Transgressing Tantric Vows from StudyBuddhism.com

- Root Bodhisattva Vows from StudyBuddhism.com

- The Benefits of Protecting the Eight Mahayana Precepts from LamaYeshe.com

- Benefits of Taking Vows from LamaYeshe.com

- Good Karma: How to Create the Causes of Happiness and Avoid the Causes of Suffering by Thubten Chodron

Please support us so that we can continue to bring you more Dharma:

If you are in the United States, please note that your offerings and contributions are tax deductible. ~ the tsemrinpoche.com blog team

There are many types of mind and behaviour existed around us, the vows are designed for everyone, people with good moral conduct will find the vows easy to follow. I came to understand and realized that holding vows is very important and for our own good.

The vows are designed in a way to help us of not creating additional negative karma.Thank you very much for sharing this knowledgeable post .

Greetings rinpoche! Hello pastors. I had a question regarding bodhisattva vows. Are bodhisattva vows taken in a proper ceremony like the refuge vows? Can we take them by ourselves on our own? And are formal refuge taking ceremony necessary for taking bodhisattva vows? Thank you

Dear Pastor Adeline, I have a question about the boddhisatva vows. Shall a practitioner go over reading the vows every day? My understanding is with the lay vows for example we recite them every morning, but the boddhisatva vows seem to me like a general description of actions to be abandoned, which sometimes might come quite natural to someone’s life. Is it anything more specific you could advice? Thank you? Chrissa

Dear Chrissa,

Thank you for your kind comment.

Rinpoche advised us to recite the bodhisattva’s vows daily:

1) to contemplate and familiarise ourselves with the vows

2) to receive the blessings of the Three Jewels

The bodhisattva’s vows may look simple but there are very deep and extensive meaning behind. This is why various masters wrote commentaries on the bodhisattva’s vows for us who may not understand otherwise.

I hope your questions are answered. When you have some time, please watch this talk by Pastor David on the Bodhisattva vows https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xbb0giqJytc

With best wishes,

Pastor Adeline

Such a great article, and so very important. I’ve come across many videos of His Eminence’s teachings in which he reiterates that vows are the root of all attainments. As the strength of our motivation lies in your sincerity and pure intention – which can be proved if we can keep the vows.

Can this be made available in pdf too? It’s a really nice article.

Thank you, Meghna. It is good to know that our articles reach out to many and benefit many like yourself.

You are welcome to make it in pdf as you wish. We are delighted that you would consider making it into different formats to share with more people.

Thank you.

With prayers,

Pastor Adeline

I believes that holding vows is one of the most important practice in Buddhism. The vows are designed in a way to help us of not creating additional negative karma. There are many types of mind and behaviour existed around us, the vows are designed for everyone, people with good moral conduct will find the vows easy to follow. Out of the 10 non virtuous stated below, i find that keeping good speech is very important for all of us. Good speech bring joy to everyone, however negative speech is very harmful, it can inflict violent and wars!

The Refuge Vows

To refrain from the Ten Non-Virtuous Actions:

3 of the Body – Killing, Stealing, Sexual Misconduct

4 of the Speech – Divisive Speech, Harsh Words, Idle Chatter, Lying

3 of the Mind – Envy, Hatred and Malice, Wrong Views

http://resources.tsemtulku.com/prayers/preliminaries/vows-and-commitments.html

Thank you Pastor Adeline, for covering all the various types of vows that are possible within the Buddhist framework.

Looking at the vows and thinking about karma that is created one cannot help but to think that, the vows are not the prison, but what imprisons us is the very karma that we create due to doing actions that goes against the vows. Our true prison is the 3 poisons, that lead us to create all the suffering and difficulties from uncontrolled and cyclic rebirths.

Thank you Pastor Adeline for this wonderful write up and knowledgeble sharing about holding vows. I came to understand and realized that holding vows is very important and for our own good. Something to remind us for our karma. It just amazes me how Sanghas can remember few hundred vows on a daily basis. _/\_

人们普遍认为守戒律有如坐監,何必弄個”戒”來管著你?不受戒多自由呢!但詹杜固仁波切的开示关于戒律很深入让我们了解到戒律真正使我们走向自由,戒的精神是完全自由的,为什么?

实际上,我们是没有自由,因为我们不能控制我们的业力,局势,妄想和下一个转世,我们害怕失去,我们都无法拥有永恒的快乐,但戒律不仅不限制人的自由,而且帮助人走向真正的自由;不仅不剥夺人享受欢乐的权利,而且使人获得真正的永恒的快乐,不仅不让人活得很累,是让人走向究竟的大自在——解脱。

很简单,如果一个国家没有法律,你会害怕出门,因为你不知道在接下会发生什么事,你可能会被抢,你可能会受伤,你可能会被别人杀死,所以没有法律,你认为你有自由吗?实际上戒律帮助我们实现更高的成就,是通向自由的门,它让我们安全通达解脱之道。

In general, people do not like to take vows because of the fear that what if they cannot untold the vows & break any of them. Breaking a vows is like breaking a promise and that usually come with some form of punishment or suffering. This is understandable because everything that we experience in life are govern by the universal law of karma, all actions will effect in results similar to the actions.

In the context of Buddhists vows, there is no different but they works quite the opposite. Since the teaching of Buddhism is about developing loving kindness & compassion to all beings, all the actions that lead to these higher attainment can only be positive actions. When we follow the Buddha’s teaching & holding the vows that comes with it, we only create more positive actions & hence the positive results. Therefore, holding Buddhist vows in all our actions can only bring experience such as peace, harmony & happiness into our lives & while not doing so will results in the opposite. In the end, Buddhist vows are not to bind us down but to set us free from the dissatisfaction that we experience in lives.

After reading the post on Why We Become Sangha, I looked up on internet on the subject of vows and discovered this post ! What a complete and comprehensive post on all one needs to know on Vows. Thank you Rinpoche, Pastor Adeline and all the other writers for this post.

A monk needs to observe 253 vows and a nun 373 vows. My first thought was, why so many? As i carried on reading more details of the vows I realised that there are many facets of our thoughts,speech or actions that can bring harm to ourselves and others, and we may or may not know it. In our deluded minds, we may even debate on it. But if we contemplate deeper we will understand why they constituted a vow. Some harm are so subtle that our minds don’t even recognise them as harm, but in actual fact they are, for example, in the Boddhisattva Vows,it is a downfall in Patience when we neglect those who are angry with us! Some may think that neglecting is the correct approach, but in reality, when we neglect it means we did not contemplate the harm that an angry person caused himself. With Boddhicitta intention, we should altruistically help him to understand his downfall and encourage him to stop the anger.

When one observes Vows, the 5 senses is tamed. One becomes mindful of every thought,speech or action; one would want to think,talk and act correctly, abiding by the instructions of each Vow. Everyday we hold on to the Vows, is a day we habituate the mind correctly. Over time the mind will be tuned to be 100% compliant and effortlessly doing so. Then, we become the perfect vessel to carry the pure Dharma of the Buddhas, and we will become perfect vessels to benefit all sentient beings! Thus is the POWER OF VOWS – no wonder it is the ROOT OF ALL ATTAINMENTS !

With folded hands.

Vows are there to protect ourselves from ourselves. We’re our own worst enemy so to speak. As long as we’re not enlightened, by which stage vows are no longer necessary, we need these vows in order to keep ourselves from harming ourselves and others.

By holding back and refraining from taking vows, doesn’t it mean that we want to retain the licence to harm?