Theos Bernard – The American Explorer of Tibet

Theos Casimir Bernard was the third American ever to set foot in the city of Lhasa, Tibet. At a time when most people thought it impossible, he amassed the largest collection of Tibetan books, scriptures and artefacts outside of Tibet.

Theos Casimir Bernard’s life story is one filled with adventure, spiritual encounters and a worthwhile determination. He pioneered expeditions to Tibet including the famed city of Lhasa in 1937, at a time when Tibet was closed to foreigners due to a policy of self-isolation. He was only the third American ever to set foot in the once mysterious city after William McGovern in 1923 and Suydam Cutting in 1935. An avid explorer, Bernard voraciously studied both Tibetan Buddhism, and also Indian religious traditions and practices such as hatha yoga. True to this spirit, his contribution to both Indian and Tibetan studies was significant.

Returning from Tibet with what was to be the largest collection of books, photographs, film footage, and religious artefacts for over 40 years, he published works including his Ph.D dissertation in religion in 1943. The first such dissertation at Columbia University, his work was the spur for the founding of the university’s Department of Religion. Through his experiences in Tibet he developed the motivation to begin a research institute in the USA, in order to translate many works belonging to the vast amount of Tibetan literature into English. Throughout his life, he made friends with many of the highest politicians, celebrities, and scholars such as W. Y. Evans-Wentz, and the list of his Buddhist teachers is similarly impressive, including the groundbreaking Geshe Wangyal who was influential in spreading Tibetan Buddhism in the United States.

“I found the Tibetans the most gracious people on earth, and never before had I such friendship extended me by foreigners.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

Early Life & Education

Theos Casimir Bernard was born on December 10, 1908, to Glen Agassiz Bernard and Aura Georgina Crable, in Pasadena, California. Abandoned by his father when he was just two years old, Bernard was raised in his mother’s hometown – Tombstone, Arizona. Having divorced Glen Bernard, Aura Crable remarried seven years later to Jon Gordon, whom she had three more sons with. The couple raised their four sons in the deserts of Arizona, where Bernard trained as a Lone Scout, learning self-reliance and survival skills which would prove a useful experience when he later travelled to Tibet.

Theos Bernard (left) with his brothers Ian, Dugald, and Marvene in the Dragoon Mountains, Arizona, USA.

Bernard enrolled in the newly-established University of Arizona, based in Tucson, in 1928. However during his studies he was struck by a near-fatal illness, which changed the course of his life completely. On a cold and rainy day in spring, Bernard became the victim of a college hazing ritual. He was thrown into a fountain in front of one of the buildings on the campus. The result was a chill that turned into a chest cold, and later developed into rheumatic pneumonia. As the days went on, he was soon admitted to the school’s hospital, where he was treated by a medically incompetent doctor. Saving him from certain death, his mother interceded and took him home to Tombstone to be treated by a doctor of her choice. His condition was so bad that he was unable to move and had to drink fluids through a tube. As he recovered from his illness in the Dragoon Mountains, in Cochise County, Arizona, he was put under constant medical supervision, where he was slowly pulled away from the brink of death.

Returning to the University of Arizona months later, he resumed his core studies and then joined the university’s College of Law. The economic situation in the USA took a turn for the worse with the stock market crash of 1929, and Bernard barely managed to graduate with a Bachelor of Law degree (LLB) in 1931 thanks to a scholarship he had received. Working odd part-time jobs, Bernard realised that a career in law, especially given the economic climate, was not for him. He then decided to continue his education at the University of Arizona.

Theos as a young man

During his summer break he was fortunate enough to be hired as a court clerk in Los Angeles, where he was reunited with his estranged father, Glen Bernard. It turned out that Glen Bernard had been a student of Sylvais Hamati, a half-French and half-Persian Hindu yogi who had trained in the yogic traditions of Bengal. Theos found his father living near the Self-Realisation Fellowship in Mount Washington, founded by Paramahansa Yogananda and Swami Dhirananda, whom he had also studied under. It was there that Glen introduced his son to various yogic practices and Indian philosophy, as a long-term treatment for this rheumatic pneumonia. To all outer appearances, Theos had recovered from his illness but due to its severity, he had been left chronically weak and with an enlarged heart.

Returning to the University of Arizona with a renewed sense of purpose, continuing his yogic practices, he was now inexplicably drawn to the study of religion and philosophy. Developing dreams of studying further at Columbia University, an Ivy League school in New York, he was swamped with debt, as were many others during that time. That was until a fortunate occurrence, when a close friend picked up a copy of Fortune Magazine which featured Theos’ long-lost paternal uncle, Pierre Bernard, who had amassed a fortune during the economic downturn and lived among the elite in New York.

“It seemed to me that if I ever became enmeshed in the practice of law, there would never be any time left for my other studies; so I decided that I would follow the direction of philosophy.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

Travelling to New York, Theos met his uncle at the Clarkstown Country Club, where he made a significant impact due to his tan, muscular and handsome appearance. Rather than introducing himself as Theos Gordon, as he was known in Arizona, taking the surname of his stepfather, he introduced himself by his legal name Theos Bernard, stressing the connection with his wealthy uncle. It was there he met Viola Wertheim, with whom he soon entered a romantic relationship. Despite reservations and a deep rivalry between his father Glen Bernard and his uncle Pierre Bernard, Theos married Viola in a private ceremony in New York City in 1934. Moving to an apartment on the east-side of Midtown Manhattan, Viola continued her studies at Cornell Medical School, while Theos enrolled at Columbia University which he was able to afford due to the kindness of his uncle.

The rivalry between his father and uncle stemmed from the teachings they had both received from Sylvais Hamati. After founding the Tantric Order of America, Hamati had returned to India, leaving the organisation under the governance of the Bernard brothers. However the two had had a falling-out. Pierre Bernard had faced serious charges of fraud and moral violations, including relationships with his younger students. Moving to New York, he had made a name and fortune for himself by arranging marriages among the elite, and by providing liberal education and entertainment. Glen Bernard accused Pierre of disgracing the teachings for monetary and personal gain. After having Theos with Aura Crable, Glen had realised that he could not follow the spiritual path taught to him by Hamati if he continued life as a lay householder. He had divorced Aura, moved around and then returned to California to work in the mines, all the while practising the teachings he had received from Hamati in secret.

“I don’t believe there is a more lonely individual living than the well-trained yogi. Yet just as he is capable of the greatest loneliness, he is also capable of the greatest happiness.”

– Glen Bernard

It was due to these experiences that Glen did not trust Pierre at all and thought that he was using Viola to influence Theos negatively. Pierre on the other hand had thought Theos was angling to steal his wealth, since Viola was one of his primary benefactors. Neither father nor uncle were correct however, since Theos and Viola were very much in love. Despite their gruelling studies, Theos and Viola always found time to spend together on weekend breaks or short holidays in upstate New York, skiing in Canada or lazing by the beach in Cuba.

Viola Wertheim

Despite the lasting effects of his illness, which were diagnosed as potentially life-threatening by doctors in New York, Theos journeyed to New Mexico as part of a government-funded initiative to restructure tribal leadership in the area to alleviate poverty and illness amongst the Native American communities. Returning to Columbia University, Theos resumed his studies and began writing his master’s thesis. Influenced by his father’s philosophy Theos now thought that all religious experiences accessed a universal truth, the realm of the divine, but that it was obvious that certain religions provided a more accurate description of this truth than others. He classed these superior religions to be those stemming from India and Tibet. However, such thoughts were best not mentioned in academia at the time.

Agonising over his deep yearning to learn more about these religions and the need to finish his studies, he decided to combine both and travel to India. While there he could not only learn more about Indian philosophy and religious practices, but mask his trip as fieldwork for a Ph.D. Realising he could not submit his master’s thesis, a pre-requisite for a Ph.D, on the subject of yoga to the anthropology department, due to his lack of sufficient research methodology, he registered under the philosophy department, under Professor Herbert Schneider – the only professor of religion there. Rather than being an actual thesis based on prevalent scientific research methods, what he submitted was more of a personal manifesto about the state of research on the misunderstood Indian tradition of yoga. He envisioned his work as the first step to clarify this misunderstanding, especially in relation to tantric yoga.

Travelling to India

Planning to meet up with Theos’ father in India, Theos and Viola began storing their possessions and sold their apartment, having one last picnic party with their friends. Viola remained in New York to spend time with her mother, while Theos travelled back to Arizona to spend some quality time with his mother and brothers. Reuniting in San Francisco, Theos and Viola were seen off on their journey by his mother and family. After a brief stop in Hawaii, they arrived in Japan where they toured the country and took the opportunity to visit the most historic and culturally relevant sites, such as the Meiji Shrine, the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, and the Daibutsu Buddha in Kamakura. Following a friend’s recommendation the two were introduced to Sohaku Ogata, the Abbot of Shunkoin Temple, who took them to his home monastery in Shokokuji. It was there that Theos was amazed to find a Hindu monk from Calcutta, who was staying in the monastery to study Zen. Theos jumped at the opportunity and engaged the monk in discussion about his plans.

Theos at his typewriter

Travelling on, they arrived in Shanghai, China, where they were hosted for dinner by Sir Elly Kadoorie, a successful businessman and upstanding member of the Sephardic Jewish community in the city. Continuing on to Peking, they toured the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven, the Winter Palace, and the Lama Temple. All the while Theos captured photograph after photograph. Their journey to India included stops in Penang, Malaysia; and Rangoon, Myanmar, where they visited the famous Shwedagon Stupa.

They finally arrived at the destination – Calcutta, India – on September 13, 1936. Meeting Glen Bernard, they travelled to Belur Math to visit the Ramakrishna Temple, where they were given open letters of introduction to all the Ramakrishna centres across India. Viola, however, was in for a surprise. Theos and Glen had been planning to engage in intensive yoga retreats and studies with various Indian spiritual masters behind her back. However, Viola soon relented, and the three of them continued on their journey across India visiting various holy sites.

Developing a fascination with north Indian traditions and Tibetan Buddhism, they travelled to Darjeeling, where they hoped they could locate Lama Yongden, who had aided Alexandra David-Neel in her studies, but they were unsuccessful. There they visited the famed Ghoom Monastery instead. Travelling across India they visited Delhi and Agra, and once again made their way up north to visit the Golden Temple in Amritsar and Hemis Monastery in Leh. It was during this time that the three of them visited and made a connection with the Roerich family. Travelling back to Delhi, the three began another leg of their journey, this time with the sole intention of deep immersion in the country’s various spiritual traditions.

Viola decided to return to her medical training and left India to return to New York on November 5, 1936, though she had savoured the time spent with her husband and father-in-law. With his fascination with Tibet and Tibetan studies growing, Theos was advised to follow in the footsteps of Evans-Wentz, who had translated texts into English, in order to further his knowledge. Determined to enter Tibet, Theos planned to trace Alexandra David-Neel’s footsteps, hoping to reach Lachen on the Sikkim-Tibet border.

Preparations for an Adventure

“Each day is filled with beauty and inspiration. It is impossible to look thru the blue azure of the Himalayan valleys and catch a fleeting glimpse of those majestic ranges of the distant north shoving their noses up into the heavens and not be effected [sic]; I tell you, it does things to you – you want to run, fly, jump, and love all at the same time.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

Journeying to Lachen, Theos was finally able to meet Lama Yongden, in his monastery some way up the mountain behind the small village. He recounted to Viola, in one of his letters, that the old master had devoted “the years of his youth… to make [an] inner develop[ment], having attained some perfection in this direction… he is now in his eighties and his mind sparkles as a fountain every flowing under the sun of understanding.” Lama Yongden even advised Theos to follow in the footsteps of Alexandra David-Neel, in disguising himself as Buddhist pilgrim in order to reach the inner recesses of Tibet. Theos prepared himself for the adventure ahead by studying the Tibetan language in Kalimpong, while his father, Glen, returned to the United States. Without the distraction of both wife and father, Theos immersed himself in his studies and continued preparations, forging close connections with prominent members of society in the area.

Geshe Wangyal and Theos Bernard

It was during this time that Theos was introduced to a young Kalmyk Mongolian lama by the name of Ngawang Wangyal. When they first met, Ngawang Wangyal was dressed in the traditional robes of a Mongolian Buddhist monk, and made a lasting impression on Theos. Born in the Kalmyk region of Russia, Ngawang Wangyal had entered his local monastery at the age of six. At the age of 17 however, his teacher had passed away. Luckily, the Bolshevik Revolution had sent a group of Buryat Mongolian Buddhists south with the aim of securing a Mongolian state of their own. Among them were three very important masters – Sodnom Zhigzhitov, the Abbot of the Petrograd Temple; Badzar Baradinevich Baradin, a Buryat intellectual; and Agvan Dorjiev, once tutor to His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama and advisor to Tsar Nicholas II. Taking Ngawang Wangyal on as his student, Agvan Dorjiev took the young monk to Lhasa, Tibet, where he enrolled him in the famous Drepung Gomang Monastic University, following in the footsteps of the countless other Mongolians who travelled to Tibet for a religious education.

Completing his studies in less than half the average time, Ngawang Wangyal felt homesick for Mongolia. Travelling to Beijing, he had attempted to enter Mongolia but was advised against it due to Bolshevik influence in the country, which tried to stamp out all forms of religion, including the brutal murder and suppression of Buddhist monks. Staying in China, he began working as a Russian translator. It was during this time that he also learned English, and was therefore hired to accompany the British political officer Charles Bell on a tour throughout Mongolia and China.

Though he had completed his studies, Ngawang Wangyal had not completed the requirement of feeding his entire monastery in order to receive his geshe title. Having saved up his earnings from translating, he was able to return to Drepung Monastery, but was unwilling to complete the requirement of feeding the 7,000 monks there, as he felt the educational system had become corrupt. After persuasion from his close friends who belonged to an influential Tibetan family, he relented. This family even sponsored the whole event.

When Theos met Geshe Wangyal, he was only a few years younger than the Tibetan scholar. Given their closeness in age, and their love of Tibetan Buddhism, they developed a friendship that would last many years. Since Geshe Wangyal was proficient enough in English to hold steady conversations, he was able to answer many of Theos’s questions about various Buddhist texts, and even described the educational systems in Tibet’s three great monasteries – Gaden, Sera and Drepung.

While continuing his language learning, Theos was able to purchase a copy of the Kangyur, the holy spoken words of the Buddha. Overjoyed at his luck, he quickly shipped them back to Viola in New York for safekeeping, until he returned and could begin translating the copious texts. In the meantime, while in Kalimpong, Theos began plans to translate various other texts before he left for Tibet. Writing to Viola, he said:

“I have secured some manuscripts which give the lives of Padma Sambhava, Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa, Mila and his 100,000 songs. It is my aim to have the life of Padma Sambhava translated before I leave here, and also to have made a start on the others…”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

Though he had memorised over a thousand Tibetan words, speaking and listening was immensely challenging for Theos. Luckily he had the company of Geshe Wangyal to distract him, and engaged in hours upon hours of conversations regarding Buddhism and Buddhist practice, although Geshe Wangyal would never talk about tantra. In another letter to Viola, Theos wrote:

“He is a very quiet and modest sort of chap and we have some fine chats at odd intervals, for we see each other several times a week… from him I am able to get an excellent line up on the literature which exists in the country… He possesses a wonderful sense of humour so I am constantly at him for being such a sophisticated monk or rather Lama, for he has that title… Really, I have a lot fun out of him.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

It was during his time spent with Geshe Wangyal that Theos developed the motivation to start a research institute to translate Buddhist texts, practise yoga, and integrate Western science and Eastern philosophies, such as clinical trials to validate Ayurvedic principles for the betterment of mankind. This was something that he envisioned his dear wife Viola spearheading, since she had learnt Ayurvedic principles at length during her earlier time with Theos in India.

Lord Tsarong

Keeping good relations with his contacts in Kalimpong, Theos was able to visit the home of Tsarong Lhacham, who was the wife of Lord Tsarong, a diplomat and close aid to the 13th Dalai Lama. While touring the house, Tsarong Lhacham unwrapped a text kept in her shrine room, and to her amazement Theos read the title out aloud. This was the first time the lady had ever heard a Westerner read Tibetan, even if it wasn’t perfect. She was extremely impressed and told him that she would do her best to aid him in his journey. However the only person who could guarantee his entry to Tibet was the British representative in Gangtok, Sir Basil Gould. Following her advice he sent several written requests, but to no avail.

Then, on a fateful day, Theos was informed that Sir Basil Gould would pay him a visit the next day. As it turned out, Sir Gould had not ignored his requests but had simply delayed his response as he wanted to meet Theos personally. Theos made a good impression on Sir Gould, not in the least due to rumours of Theos’ savant-like mastery of Tibetan and Indian philosophy, brought about by public fascination with his passion to learn. Sir Gould offered his assistance and immediately composed a cablegram to send to the Indian authorities on Theos’ behalf. However he warned Theos that his political reach could only guarantee him a six-week stay in Tibet, as far into the country as Gyantse. As preparations progressed, he made headway in his study of the Tibetan language.

The giant banner of Chenrezig at Gyantse Monastery

Realising that he was far too young to receive the esoteric teachings he was searching for in Tibet, since they were usually only granted to those further in age and study, he began to grow a beard to mask his youthfulness. He was in his late 20s at the time. Purchasing another camera to complement the one he had brought with him from the United States, Theos packed over 22,000 feet of 16-mm motion picture film and 180 rolls of 35-mm still photography film. As he left his hotel, he was seen off by his friends and contacts he had made including Geshe Wangyal, who himself was in the midst of preparing to travel to England the very next day.

Tibet

Travelling first to Gangtok in the company of Sir Gould, Theos determined to write meticulous accounts of what happened each day so that those who read his works in the future, including his wife, would have as much information about the trip as possible. Every night he diligently sat at his typewriter to record down the day’s events, incorporating knowledge gleaned from reading various texts.

Theos Bernard and his many books

Accompanying Theos was his teacher in the Tibetan language, Tharchin, and an 18-mule caravan loaded with supplies for their arduous journey. Arriving in Nathu La Pass, a mountainous path linking the Indian state of Sikkim with the Kingdom of Tibet, they were caught in heavy snowfall. As they inched their way forward, they spent most of their time picking up the mules and horses that had fallen over. When they entered the pass itself, they added small stones to piles scattered amongst prayer flags, trying to appease the local mountain gods entreating them so that they could continue along their journey unimpeded.

On his arrival in Tibet, he first visited a Kagyu monastery in Yadong. Unfamiliar with the high altitude, the prolonged exposure to the cold Himalayan air, and a lack of the nutritious food that he was used to, Theos was soon overcome with fatigue and purging. Even so, he was able to ask the abbot of the monastery questions about the Buddhist faith, and in particular about the Kagyu lineage and the life and teachings of Padmasambhava. After resting for a couple of days in the village, the group continued their journey with fresh supplies and mules.

Theos dressed as a Tibetan official

Continuing on, they arrived at Dungkar Monastery, the southernmost monastery belonging to the Gelug lineage. His experiences there were to be one of the most inspirational for Theos. The monastery belonged to the great Buddhist master Domo Geshe Rinpoche, who had recently passed away so when he arrived the monastery was still in a period of mourning. Closed to visitors, they only invited Theos to stay there once they realised he was a student of Buddhist philosophy. However, he was forbidden to document his stay on film.

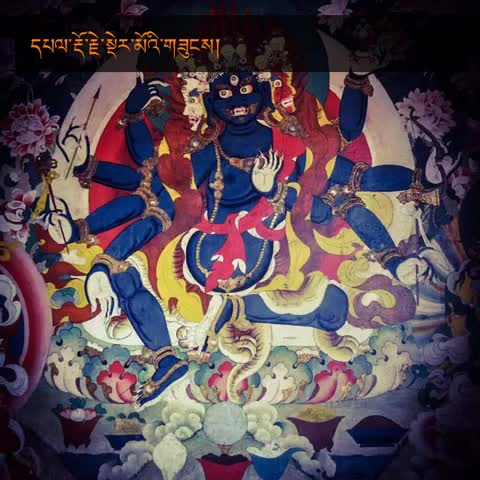

Theos was enamoured not only by the monastery but the life of Domo Geshe Rinpoche. As his stay continued he could not help but feel sadness at the loss of such a great master. He once wrote about Domo Geshe Rinpoche that “the grandeur of his work says that he held a greater religious feeling than religious understanding.” His ruminations however were interrupted when he was informed that the monastery’s oracle was preparing to take trance and that he could stay for the event. The monastery’s oracle, who facilitated the trance of Dorje Shugden and other Dharma protectors, was famed for accurate prophecies and other miraculous acts. Theos jumped at the chance, but was wholly unprepared for what he witnessed:

“We witnessed the entire performances of him entering the separate shrine where the spirit is said to dwell and listen to the chants and clashing of cymbals that are supposed to prepare him for his state and drive the spirit into him and then all of a sudden he started talking at a frantic rate of speed and writers were getting everything down just as quickly as possible and all of a sudden he ups and collapses, one of the attendants grabbing him in his arms and let him fall back into his throne gradually.

– Theos Casimir Bernard

Lighting butter lamps at Gyantse

As they continued on to Gyantse, they passed by the formidable Chomolhari mountain in Phari. In Gyantse, Theos and Tharchin approached the Acting British Trade Agent Captain Gordon Cable, who was quite unwelcoming and restricted their movements significantly while waiting for permission that would allow the explorer to continue on to Lhasa. The day after they arrived was Saga Dawa, the annual celebration of the birth, enlightenment and parinirvana of Lord Buddha Shakyamuni. Speaking to the abbot of the local monastery, Tharchin had arranged Theos to become the patron of the monastery’s celebrations. They even incorporated a long-life ceremony and a thousand-butter-lamp offering into the proceedings. During the celebrations, in front of all the monks, Theos had prostrated to the seat that His Holiness the Dalai Lama had once sat on and draped a white silk khata over it, in respect and reverence. The monks were in awe as they witnessed their first display of a foreigner profess his faith in their religion. Upon entering the monastery’s prayer halls and shrines Theos was surprised at the amount of gold, semi-precious and precious stones that adorned the statues, images and walls of the monastery, and realised that accounts he had read of such wealth were grossly understated. Paying his respects to the monastic community, Theos sponsored the tea and monetary offerings to each and every monk. It was here that Theos began his documentation of Tibetan religious life in photographs and on film.

Filming Cham dance during Saga Dawa at Gyantse

While waiting for permission to arrive, Theos continued gathering as many Buddhist texts as he could find, and documenting religious life. He was even given a thangka of Padmasambhava, and a copy of Longchenpa’s Seven Treasures, a condensed collection of works taught by Padmasambhava by Chokte, the Western Fort Commander at Gyantse. As Tharchin left for Lhasa in order to expedite the official permission to enter the city, Theos was left to fend for himself in Gyantse, which did wonders for his Tibetan language abilities. Returning to his bungalow after visiting his friend, a local Tibetan noblewoman, Theos found that a cable wire awaited him. It granted him permission to enter Lhasa and was from none other than the Regent of Tibet, Reting Rinpoche himself.

LHASA

BERNARD, GYANTSE

Recd your letter hope you recd wire from Kashag that you are much relationship may visit Lhasa as your desire wire if you need dwelling here = Regent

Theos excitedly prepared provisions for the journey, while continuing his own studies and research into Buddhist texts. He was invited to stay at the British Mission headquarters, known as Deki Lingka, and west of Lhasa but politely refused the offer as he knew they would entangle him in political matters, something that would provide him with no use for his real purpose – the study of religion. Instead he thought of the Mission to be “satisfied, egotistical, bigoted, conceited, prepossessing and anything else that you can add”. He had in fact already arranged for his accommodation in Lhasa. He would be the guest of Lord and Lady Tsarong, one of the most powerful and influential families in the whole of Tibet, whom he had made friends with on his journey. The day before he left Gyantse for Lhasa, he received confirmation once again that his journey to visit Lhasa was approved, this time from the Kashag, the governing council of Tibet:

Bernard of America

GYANTSE

Received your letter which we sent up to the Regent and Prime Minister.

As you probably know Tibet being a purely religious country there is a great restriction of foreigners entering the country but understanding that you have a great respect for our religion and have hopes of spreading the religion in America on your return we have decided as a special case to allow you to come to Lhasa by the main road for a three weeks visit.

Monks lined up at Drepung Monastery

As he drew closer to Lhasa, he first passed by the great Drepung Monastic University which housed over 10,000 monks. In awe of the buildings, he couldn’t keep his eyes off the golden roof of the Potala Palace in the distance, calling out to him. As he neared the city gates, he was greeted by an official government escort and his close friend and Tibetan teacher, Tharchin. Both men were overjoyed at their reunion, and they headed to the Tsarong estate, just south of the Jokhang Cathedral. Though Lord Tsarong and his wife, Lady Tsarong Lhacham were busy people, they had cleared the schedule to invite Theos to their estate personally since they regarded him a friend. Lord Tsarong was close friends with His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama, had been an integral part of his entourage, and was known as a brilliant strategist. He had earned the name “Hero of Chaksam Ferry” after he fought Chinese invaders, allowing the Dalai Lama time to enter into exile in Kalimpong. Being bestowed the title of the Commander General by the Dalai Lama he was charged with taking back Tibet from the Chinese, which accomplished in 1911. After a series of internal political struggles, he was one of the cabinet ministers who had implemented changes that tried to modernise Tibet, including in terms of military training. With such politically-connected and kind hosts, Theos was sure that he would achieve his aims in Lhasa.

A crowd of people outside the Jokhang Cathedral waiting for food to be distributed

Theos as the patron at the Jokhang Cathedral

He was given rooms perfectly suited to his needs, and was surprised at the amenities he was afforded. Copious amounts of floor cushions, covered with heavy and intricate Tibetan carpets; a separate bedroom; store room for his luggage; a modern toilet; towel rack; and bathtub. In fact Theos was noted as saying “it was all much better than many places I had been in India”.

One of his earliest conversations with Lord Tsarong, as far as his work was concerned, centred on acquiring a copy of the Kangyur and Tengyur. While the Lhasa editions were well done, he was informed that copies of the Narthang or Derge editions were the best. The Lhasa editions were printed from wood block which had seriously deteriorated over time, whereas the Derge editions were printed from cast iron blocks, meaning that reproductions were of a higher quality. The lord suggested Theos to leave Tibet via China rather going back down south to India. This would mean Theos would pass through Derge on his way out, where he could acquire a copy of the texts for himself.

Learning that Reting Rinpoche, the Regent of Tibet would be returning to Lhasa in a couple of days, Theos hurried himself in preparations for the meeting. Reting Rinpoche, though considered young and inexperienced, was said to have been shown favour by the 13th Dalai Lama shortly before the later passed away:

“At the time he gave the young Reting his own divination manuscript and dice, supposedly telling him, ‘I have been using these and they have proved good and if you use them it will prove useful for you too.’ Reting’s supporters argued that this was a sign that the late Dalai Lama wanted him to become regent. Reting was also famous in his own right for having performed several miracles as a child.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

Both somewhat apprehensive of their meeting, Theos and Reting Rinpoche soon found they both shared the same passion, the study of Buddhism. Reting Rinpoche even told him that his fascination with Buddhism stemmed from a previous life, in which Theos would have been a devoted practitioner. Discussing various points of the Buddhist path, Reting Rinpoche asked Theos to list down all the materials that he wished to have, and the regent would try to accommodate him.

“There was no doubt about him being a truly spiritual individual but at the same time very keen, for his mind was sharp and grasping, as well as filled with ideas. Along with it all was a remarkable sense of humour… In our conversation, all the seeds of the future were planted and also for my return, etc. He is now anxious to watch my work and help me if necessary by giving my personal disciples his personal blessings; so that means that I will probably be granted the privilege of returning to this land and brining friends with me by the mere asking – and as it stands today, I am the first American who has ever seen him.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

He spent the next couple of days meeting various ministers and members of the Kashag, as well as touring the grand Potala Palace, which included the gold-plate funerary stupa of His Holiness the Great 5th Dalai Lama covered with jade, turquoise, ruby and coral. Of particular interest was the Zhol Publishing House, known as the Parkhang, which had the printing blocks of the Lhasa edition of the Kangyur that he had sent home to Viola when he was in India.

Excited to visit the Jokhang Cathedral knowing its religious significance, Theos and Tharchin hurried there a couple of days later. Built in the 7th century the cathedral housed one of the two holiest statues in all of Tibet. Theos was however sadly disappointed by what he found. Apart from the holy statue itself the cathedral was overrun with mice, no light or ventilation and a thick layer of soot from the butter lamps, masking the wall frescos of the enlightened deities which covered the interior of the cathedral.

Theos and Reting Rinpoche, the Regent of Tibet in Lhasa in 1937.

Determined to improve Theos’ skill in the Tibetan language, his friend Tharchin began eating his meals alone in his room. This forced Theos to eat his own meals in the company of Lord and Lady Tsarong. Even so, Theos was able to talk with Lord Tsarong well enough to devise plans to convince the Kashag to extend his stay in the city. During a meeting with Reting Rinpoche in regards to his duties to the government, Lord Tsarong mentioned that Theos had wanted to arrange a tea party for the entire Kashag. Reting Rinpoche replied that in fact he himself had wanted to arrange such a party for Theos when he returned to Lhasa in a month’s time. In a roundabout way, that was the regent’s way of saying that Theos’ visa to remain in Lhasa has been extended, and Theos was overwhelmed at the news. With the extension of his stay, Theos buried himself in learning and research.

Wanting to sponsor a puja at the Jokhang Cathedral and Ramoche Temple, Theos was soon inundated by the amount of preparation necessary to complete the task and had to fall back on Lord Tsarong to help, which he did readily. Not only did he help with financial arrangements, he also organised purchase of new silk khatas, monetary offerings to all the monks, 800 pounds of butter, 1000 pounds of barley flour and 400 men that were required to carry it into Lhasa.

Theos visited many of the holiest sites in Tibet

Visiting Reting Rinpoche before he departed for Reting Monastery, Theos once again made it known that he wanted to stay in Tibet for more than the originally allocated three weeks. In a matter-of-fact manner, Reting Rinpoche said that he had brought it up to the Kashag, and they had granted everything he had requested. The regent then bade him farewell with the traditional silk khata, a red protection string, but also gave him a Buddha statue and an illustrated copy of the Sutra of the Fortunate Aeon.

On a Thursday, a day that was deemed auspicious by Jokhang’s astrologer-monks, Theos sponsored a grand puja at the Cathedral. The puja was graced with the presence of the holy representative of Lama Tsongkhapa on earth, holder of the Gaden throne and supreme head of the Gelug lineage, His Holiness the 93rd Gaden Tripa Yeshe Wangden. Having made three prostrations to the great master, he offered the traditional offerings of body, speech, and mind made by the sponsor. Throughout the puja he was sometimes asked to walk through the rows and rows of monks in a symbolic gesture to remind them that he was the sponsor of their tea, food and monetary offerings. After three more hours, both Theos and Tharchin were excused as they were told the puja would last well into the night.

Rather than leave straight away, the two men distributed money to the beggars outside of the cathedral and arranged for the blessed food offerings to be distributed to the poor and those in prison. While Theos continued his research, Tharchin was so busy running around Lhasa finding books, purchasing statues and thangkas, and stocking up on daily necessities that he wore out the soles of his shoes, and had to buy a new pair.

Theos at Drepung Monastery

Receiving a message from the abbot of Gyume Tantric College, who had officiated the puja at the Jokhang that Theos sponsored, he told them of a Guhyasamaja Tantric Empowerment at the Ramoche Temple the next day, and asked them to attend and sponsor. Theos and Tharchin happily obliged, taking the opportunity to document as much as they could on camera.

Deciding to go on a tour of the three great monasteries, Theos first travelled to Drepung Monastery where he took the opportunity take more pictures and footage of the monks and daily religious life. He even sponsored tea, food and monetary offerings to the entire monastery, and was then received by the abbot at Nechung Monastery nearby. Continuing onwards, he made an offering of 1,000 butter lamps at the stupa of the late Dalai Lama, food offerings to the monks of Namgyal Monastery, and visited the Norbu Lingka, the summer palace of the Dalai Lamas. All the while in the back of his mind he worried about getting hold of a copy of the Derge edition of the Kangyur and Tengyur, given growing tensions on the border with China, hampering his plans to leave Tibet in that direction and acquire a copy of the texts. However the gracious Lord Tsarong gave Theos his own copies, worried that Theos might actually leave Tibet using this route and lose his life in the border skirmishes.

Monks in front of the main prayer hall of Sera Monastery

Theos continued to make offerings at Sera Monastery, where he was given an extended lunch break by the monastery’s officials. Approaching Gaden Monastery a couple of days later, Theos wrote

“It was really a thrill and stimulated something inside that no other sight could bring about, providing you had ever any ideals on what a perfect monastery should be like so far as its physical structure. Here it was among the gathering clouds of the heavens and complete hidden to anyone passing up and down the valley. It would only be a chance in a million that anyone would discover it, providing there was no knowledge of its existence.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

During the following day’s ceremonies at Gaden, Theos had grown somewhat weary of the process of making offerings and having to sit through hours of puja. However when his turn came to make offerings His Holiness the 93rd Gaden Tripa, His Holiness spent a longer time than usual in bestowing his blessings by touching Theos’ head. At that time Theos felt the strange but comforting glow of spiritual presence, which stirred his mind emotionally. For Theos, such an emotional impact simply through touch was a sign of Gaden Tripa’s profound spiritual attainments.

Theos took hundreds of thousands of photographs of the Tibetan people

Coming away from his experience, Theos realised he now had a low opinion of most of those with the monastic system, which had “developed into a social mechanism to provide for those unable to cope with the demands of life”. Following this he also realised that “the head lamas of these large monasteries are one of two personality [types] – political racketeers or a true spiritual master which is the case with [Tri] Rinpoche, but these are few and far between”.

Following his experiences in monasteries, Theos came to the conclusion that the future of mankind lay a new world religious leader, well-versed in Buddhist philosophy that was something he viewed as distinct from religious practice. Yet he also realised that in order for this philosophy to be spread in the materialistic East, it would have to be couched in something he had grown a particular distaste for – ritual.

“Thru our extensive educational system we have developed a semithinking man who no longer can except traditional ritual which gives him no intellectual satisfaction; however he is in just as much in need of ritual as those in the beginning, but a new scheme of pomp must be devised for him – which in turn will also be worn out with time when the same cycle will have to take place one again, and I fear that man will never escape from the cycles of a ritual way of life – we all like clothes, but not those worn by our grandfather.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

On his way back to Lhasa, Theos stopped by a retreat hermitage known as Dra Yer Pa, where he had an audience with a Kagyu yogi who had been meditating in a nearby cave for many years. There he was given empowerment into a lineage of Tummo, or inner heat meditations, within the lineage of Milarepa, marking his entry into Buddhist tantra, to the astonishment of the local monks. Returning to Lhasa, he set about copying the texts concerning the practice that the yogi had lent him, and gathering and packing many others to take back with him to Kalimpong. He had gathered so many items, he had to spend days just overseeing tailors sew covers for all his books. Meeting Reting Rinpoche once last time in 1937, Theos left Lhasa for Shigatse, arriving in late September. There he once again made food, tea and monetary offerings at the monasteries there.

On his way, Theos was received at Sakya by the Sakya Trizin’s household and given accommodation at the Phuntsok Palace. Upon his meeting with the Sakya Trizin, he was struck by his presence and felt as though they could have been life-long friends, and even a slight and instantaneous affection for him. On October 9, 1937, Theos packed his bags for one last time, and began his journey back to Sikkim.

Preparing to leave. In from of the Himalayan Hotel.

Theos became a celebrity due to his travels. He was featured in Family Circle on April 22, 1938.

Returning to America

Arriving in India, Tharchin mobilised himself in promoting Theos’ adventures. As he began to gain prestige for his achievements, he soon received a message from Viola informing him that her mother had died of cancer. Urging him to continue his academic career, she paid for his commercial plane ticket to London, England, where Theos hoped he could apply for a degree at Oxford University. Back within high society, Theos made his presence and exploits in India and Tibet widely known, becoming a minor celebrity. However, he soon returned to New York.

When he returned he had hopes of starting some form of institution, school, research centre or ashram which would promote the practices of Indian yoga and Buddhist philosophy. His determination to open such an institution was in stark contrast with Viola’s own plans in continuing her medical career and starting a family. The two soon became distant and eventually divorced.

It was during this time that, in order to make his dream a success, Theos began marketing himself as a celebrity, riding on the fame that his adventure brought him and his story was published in newspapers and magazines across the country. He even lectured about Buddhism but with a large helping of showmanship to enrapture his audience. Resigned that he would never be admitted into Oxford University in England, he soon authored a thesis which he submitted to the philosophy department at Columbia University in New York.

This photograph was featured as the first image of Theos’ publication Penthouse of the Gods.

He wrote and published several books about his journeys, but many of them were embellished to pander to public imagination and the desire to read about the exotic, such as his memoir Penthouse of the Gods. These embellishments were actually based on the life experiences of his father, Glen Bernard who had travelled to India as a young man and been initiated into the practices of various Indian traditions.

However he did in fact publish other more accurate works on the basic principles of both Indian and Tibetan Philosophy. Both his showmanship and the embellishment in his works have led people to label him a controversial figure, despite all that he achieved during his lifetime.

He completed his Ph.D. degree in 1942, graduating for the last time, from Columbia University. His dissertation titled Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience paved the way for the university’s Department of Religion, and was a seminal piece of writing that introduced yoga to the American public.

Moving to Santa Barbara, he established the Tibetan Text Society, but it was to be short-lived. He returned to India in search of more materials and a deeper understanding of Buddhist Philosophy in 1947.

Theos when he travelled back to India

Travelling Back to India

After a not-so-amicable divorce from his second wife, Ganna Walska, a wealthy Polish opera singer, Theos travelled back to India with his third wife, Helen Park. On his way to back to Kalimpong he even had the opportunity to meet both Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. In Kalimpong, Theos found his old friend, Tharchin working on various projects and publishing a newspaper. There he also found Geshe Wangyal again.

Geshe Wangyal had returned to Tibet to live in Lhasa after arriving back from England. When they last met, as Theos was leaving Kalimpong for Tibet, Geshe Wangyal was leaving Kalimpong for England. While in Tibet, Geshe Wangyal had seen the communists gaining ground in China, and remembering what had happened when the Soviets had invaded his homeland, he tried to warn the Tibetan leaders of the danger. But they had not listened to him. Realising he could only save himself, he had relocated to live in Kalimpong in India.

Overjoyed at his good fortune, Theos resumed his studies under Geshe Wangyal, together with his new wife Helen. Wanting to study Lama Tsongkhapa’s Ngam Rim Chenmo, or The Great Exposition of the Stages of Secret Mantra, Geshe Wangyal told Theos that he must first master sutra. Instead Theos was instructed to study the Lam Rim Chenmo, or The Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment, which he readily accepted. Geshe Wangyal however found that Theos did not have a firm grasp of sutra to be able to comprehend its true meaning, so began teaching him easier subjects first, such as the Wheel of Life, or the Three Poisons.

Helen Park

Hoping to once again visit Tibet, and perhaps see the Monlam Festival in Lhasa, Theos sent numerous requests to the British Residency in Gangtok, seeking a travel permit to enter Tibet. However due to the growing political tensions in the region, the permit was refused. The British authorities even sent word to the Nepali authorities in Kathmandu, in order to block Theos if he tried to enter Tibet via Nepal. Resigned to remain in Kalimpong, he continued his studies and made plans with Helen to set up a Tibetan studies school on the west coast of the United States.

His studies progressed and he was able to translate small portions of the Lam Rim Chenmo into English. This wasn’t just a literal translation but one that conveyed its deeper meaning. His elation towards his work was soon ended by Geshe Wangyal, who put him in his place. Although he felt annoyed at Geshe Wangyal’s low opinion of the grasp of Buddhism by Westerners, Theos admitted that Tibetan Buddhists “have a fairly accurate estimate of human nature and have all mankind divided up into a few simple types of mind,” and that this determined “what kinds of knowledge… should be given to each type”.

It was around this time that Tharchin sent word of a great master coming from Lhasa to give teachings on the Lam Rim Chenmo at the nearby monastery of Tharpa Choling. As it turned out when Lord Tsarong had heard that Theos was back in Kalimpong, he entreated his good friend Dardo Rinpoche to allow Theos to attend his teachings. Over the course of a month, every day from noon until 6pm Theos, accompanied by Geshe Wangyal, attended the teachings. During the breaks Theos would question Geshe Wangyal as to the contents of the teachings, since Theos was unable to keep up with Dardo Rinpoche’s spoken language and grasp the meaning at the same time. Fortunately for Theos, Geshe Wangyal had the entire Lam Rim Chenmo “virtually memorised”.

Coupled with his study of the Lam Rim, Theos searched for books on the topic of the Twelve Links of Dependent Origination, the bardo, and yoga, having them shipped to the United States, waiting his arrival back to his home country. As the political scene in India now not only involved the independence movement, but the increasing rivalry between Hindus and Muslims, the effects could be felt in Kalimpong. Theos decided that he should travel to Kashmir and enter Tibet there. Geshe Wangyal strongly advised against the idea, but Theos was determined.

Travelling down to Calcutta, Theos and Helen gathered their supplies and boarded a train for Delhi. But with the planning of the partition of British-controlled India into two separate countries, India and Pakistan there was huge migration of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. Adamant, Theos and Helen continued their journey nonetheless. Arriving in the Kulu Valley, they settled in to enjoy the last days of the British Raj amongst the privileged classes. There they met Nicholas Roerich and family, with whom they discussed their plans of recovering rare manuscripts from Ki Monastery and Hemis Monastery in Ladakh.

Ki Monastery

When Partition was officially announced, soon there were stories of the violence. This did not change Theos’ mind and he continued northwards. Leaving Helen in the safety of the Kullu Valley, he set off accompanied by his companion Senge. Just days later Helen started to get very worried, as news of violence getting closer to the valley began to come in. Things began to heighten and then three of Theos’ Muslim porters were found dead, with their throats slit. In the midst of the ensuing chaos, she determined to await Theos’ return. She was forced to leave however with the group of Major Hotz. Arriving in Simla on October 20, 1947, she had to wait for two whole days just for a second class ticket on a train for Delhi, given the huge migration of people from all areas of India, coupled with those trying to escape the violence. On the other side of India, Svetoslav Roerich, son of Nicholas Roerich, reached the American vice consul in Calcutta, informing them that Theos was lost in the Himalayan mountain ranges between Spiti and Lahaul, as he had received word of possible sightings there.

Various articles about Theos were published. Here we see an article published on October 21, 1947 in the New York Times.

Both Helen and Svetoslav tried their best to persuade the authorities to help search for Theos but the country was still in chaos. Helen even went as far as having articles published about Theos being missing in the newspapers. Distraught, she took a train to Calcutta and returned to the same hotel that she visited with Theos just months earlier. But he never returned, and Helen decided to leave for Hong Kong as she had originally planned to do after her trip to. She left India, never to return.

Theos and his companion Senge were never heard from again. They were presumed to have died amidst the communal clashes on their way back to Helen in the Kulu Valley. His father, Glen Bernard, did not give up hope. He held on for many years, but even as Theos’ published works continued to be reprinted, he was forced to make a public announcement to state the facts regarding his son’s disappearance:

In 1947, Theos Bernard was on a mission to the Ki Monastery in western Tibet in search of some special manuscripts. While on his way, rioting broke out among the Hindus and Moslems in that section of the hills; all Moslems including women and children in the little village from which Theos departed were killed.

The Hindus then proceeded into the mountains in pursuit of the Moslems who had accompanied Theos as guides and muleteers. These Moslems, it is reported, learning of the killings, escaped, leaving both Theos and his Tibetan boy alone on a trail. It is further reported that both were shot and their bodies thrown into the river.

To date we have not been able to get any authentic information on the entire circumstances of his death, nor have we any line of the effects Theos had with him. That region of Tibet is so very remote that it is unlikely we shall ever learn the full details.

Over the course of the years, Theos’ family and friends all tried to locate him or find out what had actually happened but to no avail. Eventually, compiling all the reports and investigations, Helena filed papers to legalise his death in the United States.

Legacy

“It should be thought very strange if one’s hands and feet refused to behave, or behaved in a manner which showed that their owner had no control over them. Yet that is how too often human beings allow their most delicate instrument, the mind, to behave.”

– Theos Casimir Bernard

It was Geshe Wangyal, who had tutored Theos, that established a Tibetan learning institution in the United States. Here Geshe Wangyal stands in front of Columbia University in 1958.

Though Theos never lived to see his dream of a Tibetan studies school being established on American soil, it became a reality through the efforts of his friend and mentor Geshe Wangyal. Arriving in New York in 1955, Geshe Wangyal was brought to United States by the Mongolian Kalmyk community in New Jersey who were in need of religious direction. Learning of his arrival, Thubten Norbu, the brother of the Dalai Lama came to his aid. Through his contacts, he got Geshe Wangyal a job teaching at Columbia University where Theos once studied. Later Geshe Wangyal did establish a school, along the line of studies at Drepung Monastery as Theos had envisioned, but in New Jersey instead of on the west coast. With his founding of such a school, Geshe Wangyal had officially established Tibetan studies in the United States. Theos’ dream had finally come true.

Sources:

- http://c250.columbia.edu/c250_celebrates/remarkable_columbians/theos_casimir_bernard.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theos_Casimir_Bernard

- Barbarian lands: Theos Bernard, Tibet, and the American Religious Life by Paul Gerard Hackett

- Theos Bernard, The White Lama: Tibet, Yoga, and American Religious Life by Paul G. Hackett. Columbia University Press. 2012

For more interesting information:

- Walter Evans-Wentz: American Pioneer Scholar on Tibetan Buddhism

- Kazi Dawa Samdup: a Pioneering Translator of Tibetan Buddhist Texts

- Herbert Guenther – Master of Languages & Buddhism

- Professor Garma C.C. Chang – The Illustrious Pioneer

- John Blofeld and His Spiritual Journey

- George Roerich – Light of the Morning Star

- Bill Porter (Red Pine): The Translator of Chinese Poems and Promoter of Zen Buddhism

- In the Footsteps of Joseph Rock

- Danzan Ravjaa: The Controversial Mongolian Monk

- Agvan Dorjiev: The Diplomat Monk

- Ekai Kawaguchi – Three Years in Tibet

- Lama Anagarika Govinda: The Pioneer Who Introduced Tibetan Buddhism to the World

- Alexandra David-Néel

- Amongst White Clouds – Amazing!

- Nicholas Roerich & art (1874-1947)

Please support us so that we can continue to bring you more Dharma:

If you are in the United States, please note that your offerings and contributions are tax deductible. ~ the tsemrinpoche.com blog team

Theos Casimir Hamati Bernard was an American scholar, explorer and author, known for his work on yoga and religious studies, mainly in Tibetan Buddhism. He made an extraordinary pilgrimage to Tibet in search of adventure and spiritual enlightenment. During his journey, he collected manuscripts, paintings, prints, and sculptures that he intended to be used in teaching esoteric Buddhist studies in America. He was the founder of the first Tibetan Buddhist research institute in America. Being the third American in history to reach Lhasa, Tibet and self-proclaimed “White Lama.” He was the first American to write a dissertation on the subject of Tibetan Buddhism as well. He wrote and published a number of books , newspaper articles and a personal memoir about his accounts ,experiences of the theory and practice of the religions of India and Tibet. The Legacy of Theos Bernard continue to this day with his collection of books, art, photography and thangkas. Interesting read.

Thank you Rinpoche and Pstor Niral for this sharing.

I came to know about him ……… Theos Bernard, from his book “Hatha Yoga” which I bought way back in the 70s He was an accomplished hatha yoga master based on all the yoga poses he personally demonstrated in his book ……. especially coming from a “yellow devil” which is almost un-beleivable !

It is somewhat unfortunate that Theos did not see his dream come through, a consolation would be that at least Geshe Wangyal his tutor established a Tibetan School in the United States.

Reading this article it really felt like Theos was having a learning adventure of his lifetime. going here and there talking, and amassing teachings all over. Almost like he was the Indiana Jones of learning Buddhism.

Theos Casimir Bernard the self-proclaimed “White Lama,” became the third American in history to reach Lhasa, Tibet. As an avid explorer, author ,he studied Tibetan Buddhism, Indian religious traditions and practices such as hatha yoga. He has an interesting life and he has translated a number of books to English. He made an extraordinary pilgrimage to Tibet in search of adventure and spiritual enlightenment. Theos Casimir Bernard travel and along his route he met , and corresponded with many social, political, cultural leaders and high politicians of Tibet. He accumulated many books, artifacts and determined to acquire the important religious texts, artwork, so he can continue his studies of the language and culture.

Thank you Rinpoche for sharing these interesting and inspiring read.

It is indeed rare to come across individuals like American explorer ,Theos Bernard. A trail-blazer, he set out to find his way into Lhasa, the forbidden city, at a time when Tibet ‘s doors were still firmly closed to the outside world

There was an all consuming passion and thirst in Theos Bernard for deep knowledge of philosophy and religion especially of India and Tibet. He became fascinated with Tibetan Buddhism .His expeditions into Tibet made possible because of friendships with the highest politicians and celebrities, were very successful ones, as he learnt more and more about the religion (Tibetan Buddhism)and the monasteries that he had the good fortune to visit. Besides that, he learnt and attempted to master the Tibetan language.

Wherever he went, because of his sincere motive to learn more about Buddhism and to spread Tibetan Buddhism in the West, he met with people who were helpful and kind. One of his most invaluable friendships was that with a Mongolian monk, Geshe Wangyal, a very sharp authority on Tibetan Buddhism, who later became influential in spreading Buddhism in the US. Geshe Wangyal became his spiritual mentor and friend, who taught him and helped him navigate his way through his study of Tibetan Buddhism.

Theos’ experiences and encounters in Tibet are of the stuff that dreams are made of, considering that Tibet was at that time “a forbidden land”. He was able to visit the three great ‘Tsongkhapa’ Monasteries of Drepung, Sera and Gaden. Of Gaden as he was approaching it, he wrote of his feeling of awe of a place that was like a heaven on earth, a perfect monastery. He was enthralled with Dungkar Monastery and with the life of Domo Geshe(who had passed away when he arrived) . He saw the grandeur of Dungkar Monastery as reflecting the greatness of Domo Geshe.

When the hand of the 93rd Gaden Tripa touched his head in blessing, he felt the” comforting glow of a spiritual presence”. This left such a deep impression on him that he began to feel that monasteries should exist to produce such rare spiritually attained heads.

.

Theos also had other rare and precious experiences like the opportunity to study the Lamrim Chenmo under a renowned teacher, Dardo Rinpoche.

So much was accomplished within such a short span of time by one individual with such a zest to learn, explore and discover.! His dream to establish a Tibetan studies institute, along the lines of a monastery like Drepung, in the United States was later realised by Geshe Wangyal. That is in a way his legacy to the West.

Thank you for this fascinating and inspiring account of Theos Bernard.

Thanks for writing this post to share with us the adventure of Dr Theos Bernard to Tibet and his life story. Those pictures are precious to me considering Tibet was not exposed to foreigner back then in early 20th century. His urgency in translating Kangyur to English and his initiative to bring Tibetan studies to the west in a way opened the door for Tibetan Buddhism. Besides, I also learn that translating Dharma text from Tibetan to English is never an easy task to bring out the very essence of Buddha’s teaching. I appreciate for what we have in this blog and youtube 🙂

Theos Bernard is of the era of Alexandra David-Neel, Nicholas Roerich and W. Y. Evans-Wentz. They were of the early wave of Westerners who were passionate about eastern philosophies and mysticism.

It looks like he helped set the stage for the lamas that escaped Tibet to find an audience in the west especially in the US, with his collections and writings. Makes me wonder who they were in their previous lives to be born in the west and do all these work to bring the knowledge of Tibet out and create such interest and bring these knowledge to the west. All these create an atmosphere where Tibetan Buddhism and studies were easily accepted, laying the foundation for the spread of Tibetan Buddhism westwards. Something to ponder.

Dear friends,

This meme is powerful. Who you hang around with and the types of attitude they have is who you will be influenced by many times and who you will become in the future. Look at your friends and the people that always surround you to know who you will become.

Tsem Rinpoche

The early and mid-20th century were truly the golden age of exploration. In those decades, you had people who pushed the boundaries of travel and exploration, and challenged social conventions and norms by going to the ends of the earth to bring back to the knowledge of a different culture, religion, way of life. They didn’t have the luxury of airplanes or mobile phones, or computers or Internet to do research, make connections and the like. If you wanted to know something, you had to go out there and get it yourself. And that’s what makes people like W.Y. Evans-Wentz, Lama Anagarika Govinda and Theos Bernard to be such interesting people. They were driven, almost to the point of obsession, in their pursuit and quest for knowledge.

But beyond this pursuit of scholasticism, they were practitioners themselves too and you have to wonder about the circumstances that led Theos to take rebirth in a family that, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, was practicing yoga and whose parents had an interest in Eastern philosophies. Exposure to such philosophies in the West would’ve been, at the time, very limited. To me, this can only be explained by past life imprints, that despite being born in a land barren of such philosophies and spiritual traditions, he was still driven towards them somehow.

One thing that did surprise me is how young he was when he did all of this. So many of his adventures took place when he was in his mid-20s because he was only in his late 20s when he departed for Tibet. I also felt a bit sad that to get his story out, he felt the need to embellish certain aspects so that it would have broader public appeal. It meant that a lifetime of work and spiritual pursuits were eventually viewed with skepticism. It’s a pity because for someone who was such a prolific archiver, his records could’ve offered an accurate, almost anthropological glimpse into another world from another time. Still, it doesn’t detract from the fact we do have those with us today, and something is better than nothing.

Thanks for the post Pastor Niral, it was a thoroughly interesting read that I very much enjoyed 🙂